Preface: The Perils of Writing History

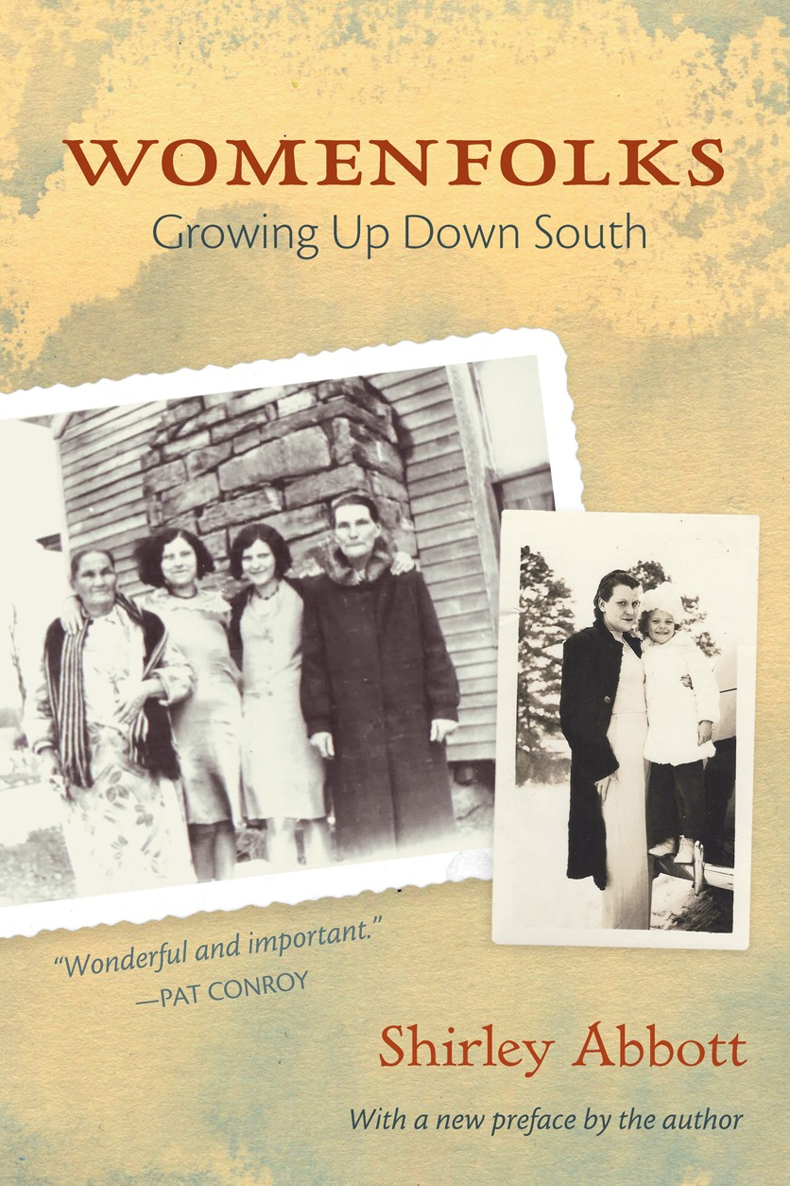

In 1983 when this book first appeared, I was a transplanted Arkansan living in New York. My work had been in the publishing industry, as an editor. I had never written a book. My editor at Ticknor & Fields was Chester Kerr, an old hand at making connections, and he gave my manuscript to C. Vann Woodward, an Arkansan like me, and a professor at Yale. He is surely still the foremost historian of the Souththe great revisionist, the groundbreaker. His book The Strange Career of Jim Crow was called by Martin Luther King Jr. the historical bible of the Civil Rights Movement.

Professor Woodward liked my manuscript, and said of it, The South of the backwoods, hillbilly plain folks has at last found its true and inspired interpreter. I am counting on that as my ticket to heaven.

Womenfolks was my unwitting gift to hima revisionist look at Southern history from the womens point of view. (The project had in fact started out, vaguely enough and six years earlier, as a survey of Southern women, everybody from Rosalynn Carter to Loretta Lynn.) As time went on, after Womenfolks appeared, Vann and I became friends. I revered his decency, his clarity of mind, his habit of siding with the downtrodden. The title of this essay is lifted from his very last book, his backward glance at how he had come to be the leader of the revisionist school. A lot has happened since 1983, and I hope here to glance calmly backward at Womenfolks. Critically. If I can manage to stay calm in these backsliding, dangerous times.

Why is writing history perilous? Why, indeed, did Southern history, as opposed perhaps to that of New England, need so urgently to be rewritten? After the Civil War and on into the twentieth century, the history of the South, as told by Southerners but not only by them, had been shaped into a few motifs that went like this: The war had been fought over states rights, not slavery. Slavery was largely benign, the peculiar institution, perfectly legal at the nations founding and no worse, really, than low-wage labor. (The South imported its slaves, it was said, while the North waited for them to arrive of their own accord, through Ellis Island.) Slavery would have died out on its own, or perhaps merely continued its necessary, civilizing mission, without the costly war forced upon the Southern states and waged so gallantly by them.

Though few historians said it in so many words, the wrong side had won in this confrontation of the gentle, agrarian South against Yankee factories, vulgarity, and greed. Ulysses S. Grant was a bumbler and a drunk, William Tecumseh Sherman a war criminal. Reconstruction was an outrage forced on a defeated region by radicals in Congress. Carpetbaggers was the term of contempt applied to reformers who came south, many of whom were said to be spinsters, i.e., unwomanly as well as unladylike. Segregation was a way of life, ordained by the Bible, beneficial to both races.

And then the meat of it: black people were unfit to vote, let alone hold office. White people had to keep them in their place. Decent Negroes wanted to remain in their place.

Vigorously promoted by scholars as well as pop culture, especially Hollywood (Birth of a Nation, Gone with the Wind, and dozens of lesser works), not to mention pop music (Thats What I Like about the South), these views were held all over the country, not just the South. They have never died out. During the presidential campaign of 2016, Cliven Bundy, the Nevada rancher and Tea Party hero, opined that black people had been better off in slavery. He was scarcely alone in this idea, which has been promoted even in some history textbooks, some of which are still in use.

As a young scholar at the University of North Carolina in the 1930s, Vann tells us (in his last book) that he nearly took up Roman history, so great was his antipathy to the work of his predecessors in the Southern field. Nothing they had said was based in fact or in plain grubby research. It was propaganda, designed to keep African Americansand poor whiteson the bottom, where they had always been, safely out of the great American game.

History may seem a dull affair, practiced by harmless pedants. But history is politics. Southern history, whether you know a little or a lot about it, directly affects how you vote. All politics may indeed be personal, but these days it is also Southern. The South, it has been truly said, lost the war but won the peace. The United States is famous for aiding its defeated enemies. If you want to improve your situation, the old joke goes, lose a war with the US and apply for foreign aid. Apart from its devastation and appalling loss of life, the postCivil War South got quite a good deal. All attempts at a new political and social order ended in 1877, only twelve years after Appomattox. Jim Crow became the law of the land, sanctified by the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, 1897. Hands off the South became a kind of loyalty oath for presidential candidates. Antilynching bills, timidly proposed in the 1930s as the numbers of lynchings rose, died in Congress. And of course the South was crucial to electing a president. Southern political power went national, and has remained so since.

When I began work on Womenfolks, about 1975, I was but dimly aware of all this. I came to my task with only my own experience in my head. I grew up among poor farm folk, descendants of pioneers, permanently altered in body and mind by the Great Depression. Subsistence farming had come to its bitter end as a way to make even a bare living. The migration to towns had begun. Indoor plumbing, electricity, and telephones were novelties to my mothers generation. At my grandmas house, you still drew water from the well. The women washed clothes on a rub-board and hung them outdoors to dry. My people still spoke the English of the backwoods. No Tidewater drawl there. They heard cheese as a plural, said I taken, and I done, and generally went their own way with past participles. All this regional speech, of course, has over the years passed into the category of Southern cute. Everybody now, even the New York Times, talks about being between a rock and hard place.

But speaking in dialect wasnt cute then. It marked us as rubes and ignoramuses, fodder for the Lum and Abner show, Al Capp, and the Dukes of Hazzard. It meant you could not get a decent job. You did not do well in school. It was a fatal class marker, rendered a little less malign because it was so widespread. Unschooled black speech was similar to white hillbilly, mellower and that much further from correct English, but was an even more malignant class marker and a universal subject of mockery. Nobody had thought of Ebonics yet.

The lot of the poor in the South, whatever their color, hardly began to improve until after World War II.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.