A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

The number of debtsintellectual, personal, professionalI have incurred in the writing of this book is staggering. My first and greatest thanks are owed to Robert E. Lerner. His support, patience, advice, humor, and friendship have been invaluable, and this book would not exist without his unfailing generosity in sharing his knowledge and the fruits of his research. I was blessed to benefit from his mentorship, as from that of Richard Kieckhefer, Barbara Newman, Edward Muir, and Dyan Elliott, each of whom has been unstintingly generous and gracious with his or her time, expertise, and editorial wisdom.

William Monter shared his thoughts on the challenges of queenship with me at an early stage in this books inception, and his perspectivelike his insistence on the importance of numismaticshelped me think through many of the conceptual difficulties Johanna faced. Daniel Lord Smail kindly offered guidance on navigating Marseilles archives. Anna Qureshi generously allowed me to read her masters thesis about misogynistic judgments of Johanna (written under Dr. Smails direction), helping to fill gaps in my reading.

Theresa Earenfight and an anonymous reader offered valuable expert criticism and insight on the manuscript that have made the book stronger.

My colleagues in the History Department and in the Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies at Binghamton University have been wonderful supporters, editors, and critics. Marilynn Desmond, Richard Mackenney, and Tina Chronopoulos have read most or all of the manuscript at various stages, and I thank them for their advice and generosity. Leigh Ann Wheeler has been a superb sounding board and crisis counselor. Thanks are due as well to Nancy Appelbaum, Ken Kurtz, Howard Brown, Steve Ortiz, Diane Sommerville, Jean Quataert, Kent Schull, Olivia Holmes, Dana Stewart, Heather DeHaan, Julia Walker, Kevin Hatch, Heather Welland, Sean Dunwoody, Jerry Kutcher, and Barbara Abou-El-Haj for their friendship and moral support.

Much of the research that went into this book was supported by the Fulbright Association, which allowed me ten months of intensive research in French libraries and archives. Much of the writing was supported by the American Association of University Women and by the Harpur College Deans office, which also funded additional research in Naples.

I have presented portions of this book to a number of groups. I presented an early version of chapter 1 at the Sewanee Medieval Colloquium in 2006. At that time, Charles Briggs offered perspective that helped direct my research going forward. I shared portions of chapter 4 with the participants in the California Medieval History Seminar (February 2009) and the Newberry Intellectual History Seminar (November 2010); both groups offered feedback and commentary that helped me better articulate my argument. I also benefited from the insight of my fellow panelists and the audience at a panel on Rumor and Infamy in Political Culture at the 2013 meeting of the Medieval Academy of America. Finally, my thinking about Boccaccios treatment of Johanna gained sharpness and clarity thanks to conversations with participants at a conference in Binghamton in honor of Boccaccios 700th birthday.

My family and friends are owed the most profound gratitude. My father, John T. Casteen III, and my mother, Lotta Lfgren, have always been my intellectual models and heroes. They have been my best editors, and they have gone well above and beyond the bounds of parental duty in their willingness to read drafts, talk through ideas, and offer moral support. I thank them, Betsy Casteen, Andy Hord, and Michael and Katherine Chang for their encouragement. My brother, John Casteen, is a tireless, compassionate listener and a beloved friend who has been quick to offer needed morale boosts. I thank Lars Casteen and Sonny von Gutfeld for their hospitality and generosity, as for their support and friendship. Jenny Miller, too, offered hospitality, fellowship, and a place to stay during a vital stage in my research. Thanks are due as well to Elizabeth Carpenter Song, Meghann Pytka, Dana Polanichka, Courtney Kneupper, Suzanne LaVere, Alex Wolff, Noah Peffer, Joel Westendorf, Candice Lin, Jon Mingle, Laurie Casteen, Lily Casteen, Luke Casteen, Alex Barker, and Lily Robinson.

Above all else, I am grateful to and for Frank Chang, whose love and friendship mean everything.

Introduction

I saw the Queen of Naples in great estate, I swear to you, in my Lady Fortunes court. No single woman in the world was more honoredand, apparently, as lovedby my Lady! For a long time Fortune maintained her, and kept her in state, but afterward, very suddenly, she turned her back most cruelly.

Christine de Pizan, The Book of Fortunes Transformation (1403)

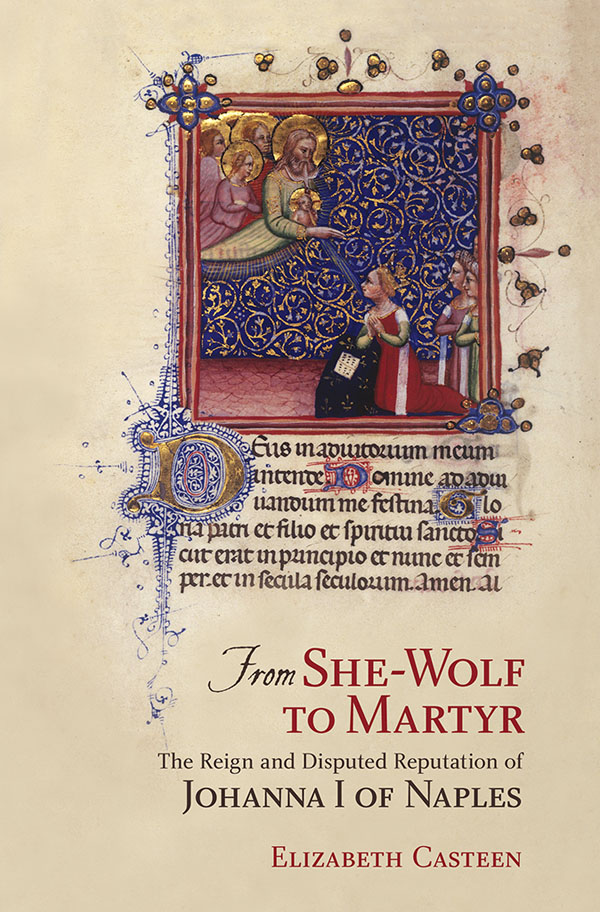

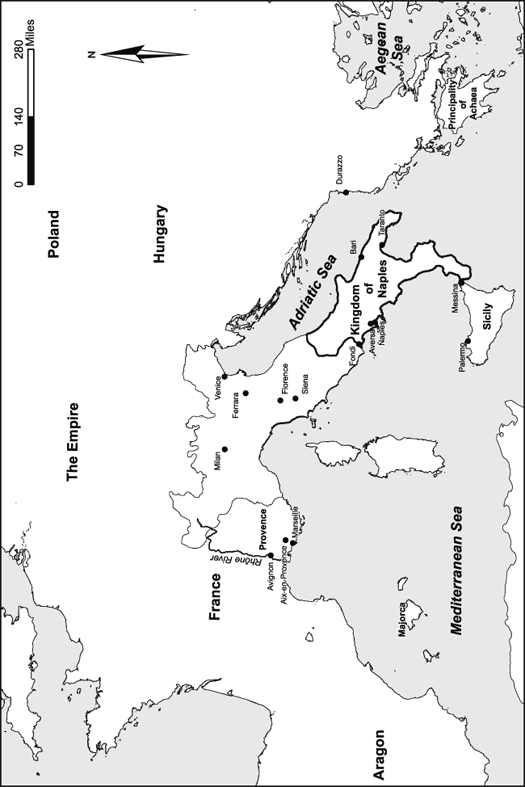

During the latter half of the fourteenth century, both Provence and the Kingdom of Naples were ruled by a woman. In both cases, the woman became vital to regional memory. Provences Countess Jeanne is remembered as pious, beautiful, courtly, wise, and committed to her subjects well-being. In the words of an eighteenth-century historian, she was a woman endowed with all the agreeable traits possible in her sex. Hopelessly debauched and voraciously lustful, she squandered her kingdoms resources until she met a fitting end, murdered by her heir to avenge decades of misrule.

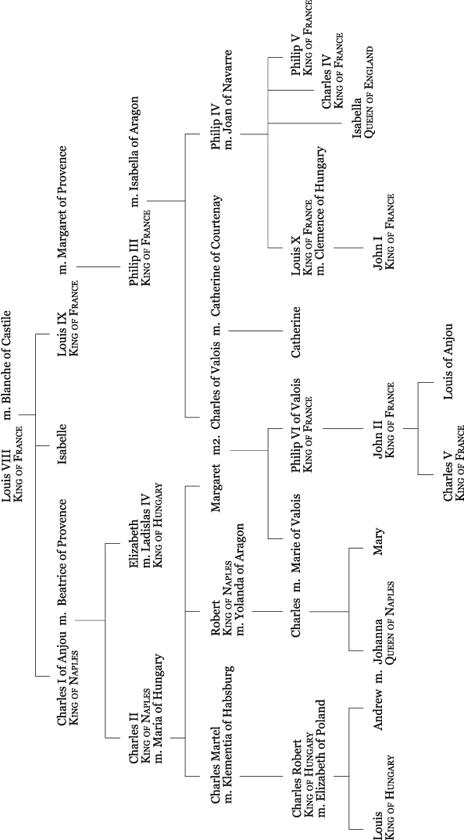

These two historical portraits appear dichotomous, but they actually describe the same woman. Variously known (depending on who was or is describing her) as Jeanne, Jehanne, Joan, Giovanna, Zuana, or Joanna, in life she was most often calledat least in writingby her Latin name, Johanna. Johanna of Naples, queen of Sicily and Jerusalem and countess of Provence and Forcalquier (r. 134382), was a controversial, complex figure in life and after her death. Her posthumous reputations serve as a reminder of the mutability of historical memory and how contingent and culturally determined reputation is: One persons Jeanne is anothers Giovanna. This book is about Johannas various, contradictory reputations; through this lens, it examines the cultural mentality of late medieval Europe, particularly diverse, multifaceted reactions to regnant queenship, female sovereignty, and Johanna herself.