This edition is published by ESCHENBURG PRESS www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books eschenburgpress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1948 under the same title.

Eschenburg Press 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

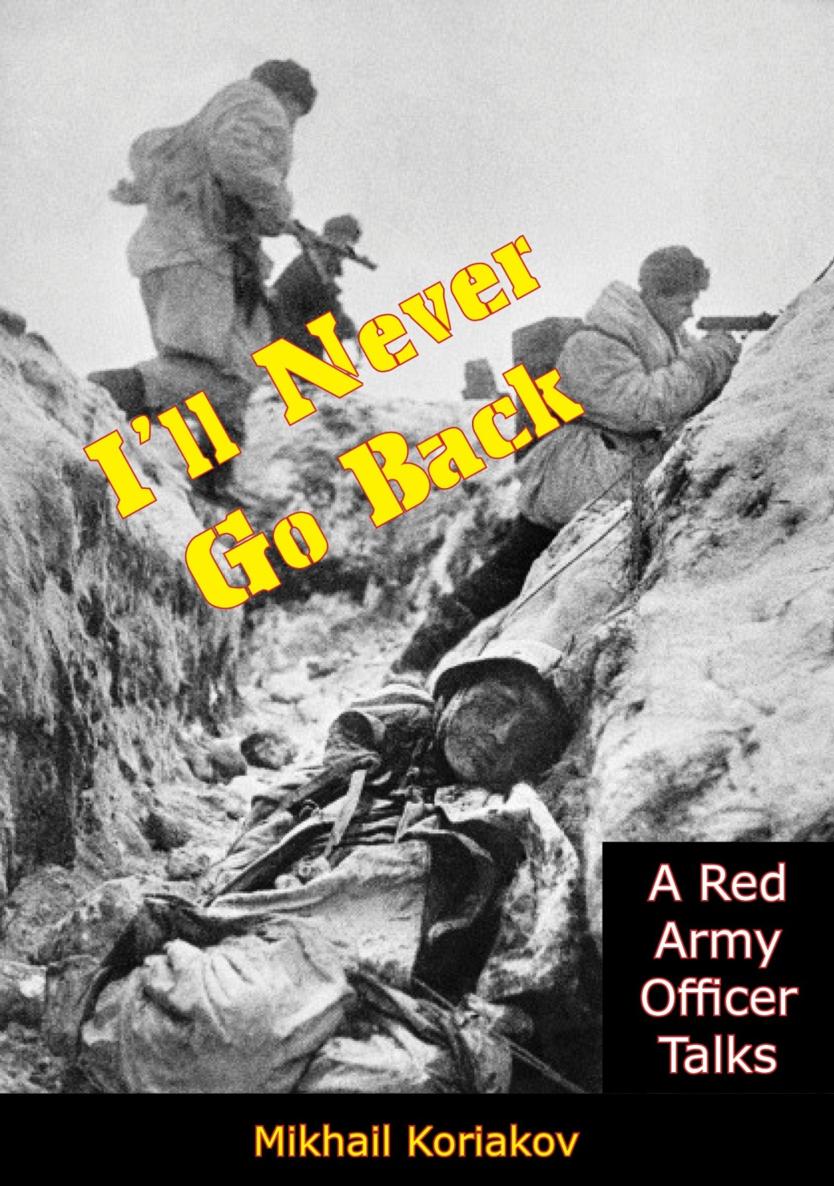

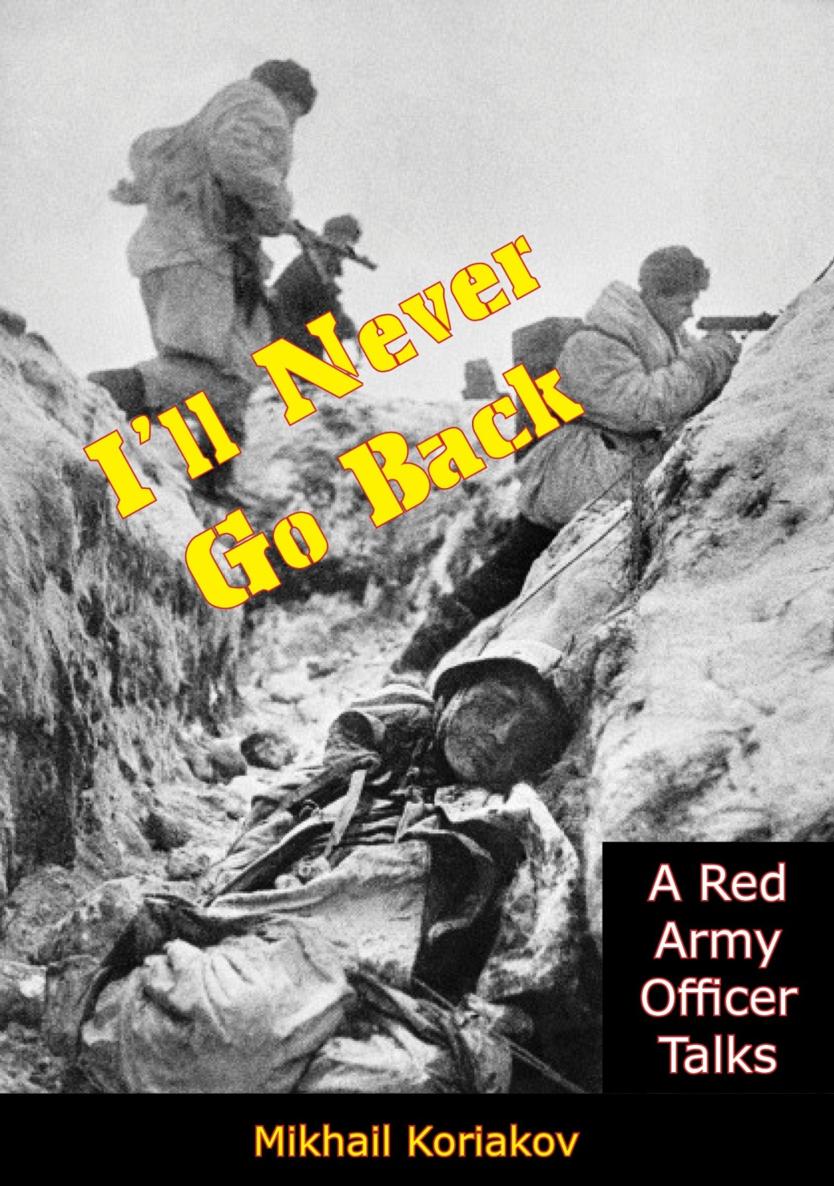

ILL NEVER GO BACK

A RED ARMY OFFICER TALKS

BY

MIKHAIL KORIAKOV

Translated from the Russian by

NICHOLAS WREDEN

Stand fast therefore in the liberty

wherewith Christ hath made us

free, and be not entangled again

with the yoke of bondage.

GALATIANS V, I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

For six years a storm had raged over the world. It lifted millions of people of all countries and scattered them over the different continents. As soon as the storm subsided and the skies cleared, the people who had forgotten light began to study one another under the low-hanging, blinding sun of the first days of peace.

Who are you? Where did the storm carry you during those years? Why are you here? Why are you on this side of the front with your enemies, instead of being over there with your people? Why are you in a foreign country, instead of being at home?

These are fair questions. Suspicious attitudes so soon after a war are to be expected. When people read in the newspapers about the hundreds of thousands of Russian non-repatriates who are hiding in the stony caves of Germany, in the mountains of Switzerland, or with the French Underground, their impulse is to say: These men are traitors who fought on the German side! These men have a bad conscience and they should be turned over to the Red Army! Such accusations cannot be easily dismissed; unfortunately they are founded on bitter truth. But people who make them should be aware of the tragedy as well as of the guilt of the Russian soldier; they should investigate the causes of such wholesale treason.

I am a non-repatriate, and I am ready to defend my stand. Beginning with the spring of 1941, and until the spring of 1945, I fought in the ranks of the Red Army. With the Red Army I travelled the long road from the walls of Moscow to the ruins of Dresden. I started out as a private and ended as a captain. For almost a year after the surrender, from May 1945 until April 1946, I worked in the Russian Embassy in Paris. Whenever I probe my conscience, I feel no reason to be ashamed; I fought the Germans until the bitter end; that is the reason why, without holding anything back, I can tell how I found myself on this side of the front at the close of the War.

This book is a document; none of the facts is distorted, and only some of the names are changed. If the reader will understand the tragedy of the Russian soldier, if he will sense the deep underlying motives of the Russian non-repatriate, I shall consider that the writing of this book has been justified.

Chapter OneREQUIEM

In the spring of 1944 the 6 th Air Force was being shifted from the North-west Front to the First White Russian Front, from round Novgorod to Volhynia, into the Lutsk-Kovel sector. The morale of the troops was extremely good; the Ukraine was clear of the Germans, the siege of Leningrad lifted; every one realized that one more blow would carry us across the borders into Rumania, Poland, and the Baltic States. My personal fortunes were also at their peak. As an Air Force military correspondent I was visiting many of the regiments and divisions by plane, I was dropping in on the different sectors of the front, I was learning a great deal, and, since there were things that could not be mentioned in my dispatches, I was trying to remember everything. My notebooks were bulging. I wanted to understand the fine points of air combat in which our flyers used new tactical formations and the enemy even more unexpected and tricky manuvres. The tactics of air combat were no longer new to me; I had learned something about this complex and exact science. The pilots in the various air regiments knew me and considered me one of them. Lieutenant-General Polynin, commanding the 6 th Air Force, decorated me with the Order of the Red Star and gave me a weeks leave in Moscow, while the troops under his command were being moved to Volhynia.

Moscow meant everything to me. There, in a narrow, winding lane, lived my family; there, on dust-covered shelves in a tiny room, were my books, which I had not touched since the beginning of the War, since the spring of 1941; there, across the Moscow River in a two-storey wooden house standing in a quiet street, lived my girl....Moscow was an essential part of all my hopes, my dreams, my plans for the future, my literary aspirations. In my kitbag was a fat, two-hundred-and-fifty-page manuscriptmy first book, which I hoped to publish in Moscow.

It was an unpretentious, factual book called A Day in the Belfry , and it described the events of a single day in a quiet sector of the North-west Front. That particular front had remained stationary for two years and all fighting had been confined to static warfare. An empty, snowy desert extended for about fifteen miles on both sides of the front line. The villages had disappeared without a trace; the houses had been burned by two years of bombing and artillery fire, or else torn down and used for reinforcing dugouts and trenches, and for building plank roads across the never-freezing swamps. In some miraculous fashion, far from the front line, a lone belfry had withstood destructionit was the only landmark on the spot where once there had been a village, Bolshaya Ivanovshchina. For two years the German artillerymen had fired at this target to no avail! Direct hits had left the altar in ruins, the walls of the church had collapsed, but the belfry, which was so valuable to us, continued to stand, its walls covered with smoke, scarred with shell fragments, and reinforced with iron bands. In the belfry our men maintained an Air Force observation point from which the German lines and their approaches could be seen with revealing clarity. The Air Force staff officers in the belfry were in constant touch by wireless with the infantry, the artillery, and the planes in the air; they directed the dive-bombers to their targets, gave orders during dog-fights that were fought as often as ten times a day over the lines, and, most important of all, co-ordinated the action of all the different branches of the service. The contents of my book dealt with what could be seen from the belfry in the course of a single day. A single day on a small, relatively unimportant and quiet sector of the front, but what an amazingly long chain of varied, colourful, and, at times, strikingly contrasting events! In order to absorb and understand the events of a single day, I had spent two long months in the belfry. The tiny, frozen sector of the stationary front was placed under a microscope and the war was revealed as a tightly constructed network in which it was extremely difficult to segregate the commonplace from the tragic or the ridiculous. A Day in the Belfry was a study in the physiology of war.