a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. New York 2009

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York,

New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton

Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of

Pearson Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL,

England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia),

250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of

Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community

Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ),

67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of

Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd,

24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

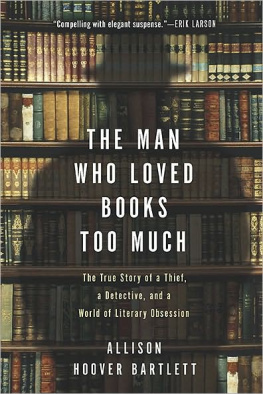

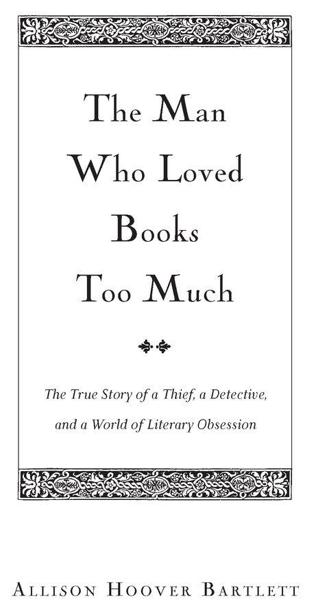

Copyright 2009 by Allison Hoover Bartlett

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bartlett, Allison Hoover.

The man who loved books too much : the true story of a thief, a detective, and a world of literary obsession / Allison Hoover Bartlett. p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-101-14030-7

1. Gilkey, John, 1968- . 2. Book collectorsUnited StatesBiography. 3. ThievesUnited StatesBiography. 4. Book collecting. 5. Bibliomania. 6. Book thefts. I. Title.

Z992.8.B.075dc22 [B]

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

http://us.penguingroup.com

For John, Julian, and Sonja

For him that stealeth, or borroweth and returneth not, this book from its owner... let him be struck with palsy, & all his members blasted.... Let bookworms gnaw his entrails in token of the Worm that dieth not, & when at last he goeth to his final punishment, let the flames of Hell consume him forever.

Anathema in a medieval manuscript from the Monastery of San Pedro in Barcelona

I have known men to hazard their fortunes, go long journeys halfway about the world, forget friendships, even lie, cheat, and steal, all for the gain of a book.

A. S. W. Rosenbach, twentieth-century book dealer

Prologue

A t one end of my desk sits a nearly four-hundred-yearold book cloaked in a tan linen sack and a good deal of mystery. My friend Malcolm came across the book while carrying out the sad task of sorting through his brothers belongings after he committed suicide. On the sack was a handwritten note that began, To whom it may concern, and went on to explain that several years earlier, a friend had withdrawn the book from a college library where she worked and had accidentally taken it with her when she moved away. He wrote that she had wanted the book to be returned to the library anonymously, but that he hadnt had time to do so. Gingerly, Malcolm lifted the large, heavy tome with gleaming brass clasps from its sack. Isnt it beautiful? he said as he handed it to me. My first thought was: Yes, beautiful. My second: Its stolen.

I woke the next morning with the book in my head. Was the story in the note true? If not, where had the book come from? I could see that it was written in German, with a sprinkling of Latin, but what was it about? Was it valuable? Malcolm agreed to let me borrow it for a while. With the help of a German-speaking friend, a librarian, and a rare book dealer, I learned that it was a Krutterbuch (plant book

The Krutterbuch weighs in at twelve pounds, and its cover, oak boards clad in pigskin, or for some other more useful purpose than sitting blankly at the front of a book. When I asked Windle about the books value, he said that because it was in fairly good shape it was worth $3,000 to $5,000. I was pleasantly surprised, although since the book was not mine, I had no rational reason for feeling such satisfaction.

Going through the book with a German-speaking friend and her mother (who was more familiar with its archaic lettering), we found remedies for all sorts of physical and mental maladies, from asthma to schizophrenia, as well as minor ailments. On page 50, for example, for a bad smell in the armpit, a long list of ingredients is recommended: pine needles, narcissus bulbs, bay leaf, almonds, hazelnut, chestnut, oak, linden, and birch, although it doesnt indicate how, exactly, they are to be used. Dried cherries help with kidney stones and worms. Dried figs with almonds are recommended for epilepsy. My favorite remedy, though, is for low spirits. Often we are missing the right kind of happiness, and if we dont have any wine yet, we will be very content when we do get wine.

Text from the reverse sides of pages in the Krutterbuch bleeds through in a ghostly way, making it seem that what exists on these pages might at any moment blend together or fade away entirely. But in 375 years it hasnt. The Krutterbuch remains much the same as when it was bound. That it hasnt lost its fullness, its ability to resist against the clasps, is one of its most awe-inspiring qualities. It seems a stubborn, righteous thing that has lasted all these years, and it took me some time to come to the realization that in turning its pages, I probably wouldnt harm it.

I had learned a lot about the book, but still had no clue where it was from. I searched the Internet for information about stolen rare books, but while nothing turned up about the Krutterbuch even the librarian from the library mentioned in the note said that they had no record of itI stumbled upon something even more intriguing: story after riveting story of theft. Some had occurred weeks or months before, others years ago, in Copenhagen, Kentucky, Cambridge. They involved thieves who were scholars, thieves who were clergymen, thieves who stole for profit, and those whom I found most compelling: smitten thieves who stole purely for the love of books. In several accounts, I came across references to Ken Sanders, a rare book dealer who had become an amateur detective. For three years Sanders had been driven to catch John Gilkey, a man who had become the most successful book thief in recent years. When I contacted Sanders, he said that he had helped put Gilkey behind bars a couple of years earlier, but that he was now free. He had no idea where Gilkey was and doubted that I would have any luck finding him. He also believed that Gilkey was a man who stole out of a love of books. This was the sort of thief whose motivation I might understand. I had to find him.

The more I learned about collectors, the more I began to regard myself as a collector, not of books, but of pieces of this story, and like the people I met who become increasingly rabid and determined as they draw near to completing their book collections, the more information I came across, the more I craved. I learned about vellum and buckram, errata slips and deckled edges. I read about famous inscriptions and forgeries and discoveries. My notebooks grew in number and sat in piles thicker than ten Krutterbuch s stored, as they would have been in 1630, on their sides. As I accumulated information about the thief, the dealer, and the rare book trade, I came to see that this story is not only about a collection of crimes but also about peoples intimate and complex and sometimes dangerous relationship to books. For centuries, refined book lovers and greedy con men have brushed up against one another in the rare book world, so in some ways this story is an ancient one. Its also a cautionary tale for those who plan to deal in rare books in the future. It may also be a lesson for those writers who, like me, approach a story with the naive belief that they will be able to follow it the way a spectator passively follows a parade, and that they will be able to leave it without altering its course.