The Pen Confronts the Sword

The Pen Confronts the Sword

Exiled German Scholars Challenge Nazism

AVIHU ZAKAI

Cover photo from iStock by Getty Images.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2018 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zakai, Avihu, author.

Title: The pen confronts the sword : exiled German scholars challenge Nazism / Avihu Zakai.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017056059 | ISBN 9781438471631 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781438471655 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Exiles writings, GermanHistory and criticism. | German literature20th centuryHistory and criticism. | Authors, German20th centuryPolitical and social views. | Philosophy, German20th century.

Classification: LCC PT3808 .Z35 2018 | DDC 830.9/00914dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017056059

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

And the divisions on the central front, under Field Marshall von Bock,

Had already sighted through their binoculars the battlements of Moscow.

Luckily for the Russians, the autumn rains fell unrelentingly,

Turning the approaches to Smolensk into the usual quagmire.

Then, in October, the snow began falling in cruel abundance,

Recalling, a spark of hope, what befell Napoleons Grande Arme

On the deadly white expanse.

We feared what spring would bring,

Dreaded, too, the forces of Field Marshal von Rundstedt,

Which, having taken Rostov, were pressing on toward

The Caucasus and the oilfields of Iraq.

And we feared the Panzer divisions of Field Marshall Rommel,

On their way to Mersa Matruh, and from there to

Why not?Tel Aviv, Ein Harod, and Jerusalem.

Haim Gouri, And the Divisions1942,

translated by Michael Swirsky

Contents

WITH D AVID W EINSTEIN

Acknowledgments

Several colleagues and friends read all or part of my work and offered valuable comments and criticism, among them, Martin Vialon, Stephen G. Nichols, the late William Calin, Martin Elsky, James Porter, Paul Mendes-Flohr, the late Menachem Brinker, David Weinstein, Stephen Whitfield, Walter Nugent, Alexander Yakobson, David Heyd, and Avraham Shapira (Patchi). I owe special thanks to my longtime editor Julie Edelson, who once again made my work shine in a new light. Finally, special thanks to Rafael Chaiken at State University of New York Press, who never ceased to believe in the worth of this study and followed it closely until its final production.

Chapter 3,

Introduction

The Age of Catastrophe

Exile and the Struggle for the Humanist Soul of Europe

Scribere est agere (to write is to act).

Sir William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England , 17651769

On February 22, 1942, Stefan Zweig, the exiled Austrian Jewish novelist, playwright, journalist, and biographer, committed suicide in Brazil. As he explained in his suicide letter, the world of my own language sank and was lost to me and my spiritual homeland, Europe, destroyed itself.

The decades from the outbreak of the First World War to the aftermath of the Second, wrote Eric Hobsbawm, was an Age of Catastrophe, or historia calamitatum . For forty years it stumbles from one calamity to Indeed World War II was an epistemological watershed in modern Western humanist civilization.

If 1942 appeared to be the nadir of civilization, that cultural low point was made flesh by what was happening on the battlefield. It was the year of the Battle of Stalingrad, the most crucial struggle of World War II, a great epistemological watershed in which European humanist civilization faced its gravest existential moment. Many contemporaries shared a general conviction that Stalingrad signifies a turning-point in the war.

In the eyes of contemporaries as well as historians, 1942 was the most crucial year of World War II because of three decisive battles on three different fronts. The Battle of Midway in the Pacific took place between June 4 and June 7, the First Battle of El Alamein in Egypt from July 1 to July 27, and the Battle of Stalingrad, Russia, between August 1942 and February 1943. These battles eventually turned the tide of the war in favor of the Allies, but in Istanbul, Auerbach could not know what the outcome would be, let alone whether the German army would reach Turkey from the south via Egypt or the north after conquering Russia. On May 8, 1942, for instance, the German army withstood a Soviet counteroffensive near Kharkov and inflicted heavy losses. The Wehrmacht was on the move and winning in Russia: it reached the Donets, recaptured the Crimea, and took Sevastopol by mid-June. Voronezh was taken while the bulk of the German forces moved toward the oil fields and the Caucasus. At the same time, Friedrich Pauluss Sixth Army advanced along the Don

It also seemed invincible in North Africa. Panzer Army Africa (Panzerarmee Afrika) under Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (18911944) started the second phase of its advance toward Egypt, and from February to May 1942, the front line settled down near Tobruk. Rommel thought his army would soon secure the oilfields of the Middle East, Persia, and even Baku on the Caspian Sea.

The year 1942 brought European humanist civilization to the brink of extinction. Wehrmacht victories in Russia and North Africa portended disaster, yet they also prompted German intellectual exiles to conceive works that took aim at Nazi barbarism and profoundly transformed the content and form of modern intellectual history. In clear contrast to Zweig, these authors stood up against the horrors of Nazi Germany, and their Kulturkampf changed the subject matter, methods, and analysis of political, economic, sociological, anthropological, literary, philosophical, and ethical discourse.

The Pen Confronts the Sword draws attention, for the first time, to the shared motives behind four remarkable texts, all begun in 1942 by exiled scholars Each identified a specific danger in Nazi ideology and mustered new theories, new approaches, new sources, and a new energy to combat it. While scholars have examined these authors individual legacies, no one has drawn them together for comparative analysis or isolated this watershed moment in their careers. The sense of urgency in their works demands attention. They all raised their pen against Nazi barbarism, believing exactly like Sir William Blackstone, the English jurist and judge, who wrote in his Commentaries on the Laws of England (17651769), Scribere est agere (to write is to act).

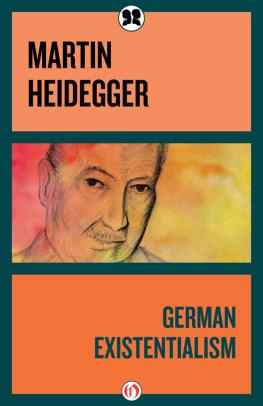

A books title reveals intention and meaning. Change the title, and youve wrested it from the history that bore it; youre drifting away from the authors understanding of its intention, content, and form. Accordingly, the titles of these books reflect, directly or indirectly, the trauma the authors experienced as their culture turned toward myth and unreason. In literature, Thomas Manns Doctor Faustus renders Nazi Germany as the new incarnation of the old German legend of amoral arrogance and ambition, equating Germanys covenant with Nazism with a contract with the devil In political philosophy, Cassirer denounced the Aryan racist mythos of Blut und Boden (blood and soil)the major slogan of Nazi racial ideology, which grounded ethnicity in a toxic mythology of blood, folk, and homeland ( Heimat )which led to systematic terrorization and extermination of people deemed alien and condemned philosophers, such as Oswald Spengler (18801936) and Martin Heidegger (18891976), for supporting the German culture of pessimism, fatalism, and paranoia, or the destructive myth of the state. In philology, Auerbach struggled against the rejection of the Old Testament and Jewish influence on European humanist civilization, history, and culture, taking up the ancient Greek debate about the value of art that imitates or reproduces reality to elevate mimesis over myth and ordinary human dignity over specious superheroes. Finally, in sociology, Horkheimer and Adorno illuminated how the dialectic of enlightenment was driven by a myth of power, first over nature, then over other people, and led to the subjugationindeed, destructionof the powerless by the powerful.