T HE G REENPEACE TO A MCHITKA

THE GREENPEACE TO AMCHITKA

An Environmental Odyssey

Robert Hunter

WITH PHOTOGRAPHS BY R OBERT K EZIERE

THE GREENPEACE TO AMCHITKA: AN ENVIRONMENTAL ODYSSEY

Copyright 2004 by Robert Hunter

Photographs copyright Greenpeace/Robert Keziere

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical without the prior written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may use brief excerpts in a review, or in the case of photocopying in Canada, a license from Access Copyright.

ARSENAL PULP PRESS

#101-211 East Georgia St.

Vancouver, BC

Canada V6A 1Z6

arsenalpulp.com

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the British Columbia Arts Council for its publishing program, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program for its publishing activities.

Edited by Mary Schendlinger

Design by Solo

Printed and bound in Canada

Library and Archives Canada

Cataloguing in Publication

Hunter, Robert, 1941

The Greenpeace to Amchitka : an environmental odyssey / Robert

Hunter ; photographs by Robert Keziere.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-55152-178-4

ISBN 978-1-55152-189-3

EISBN 978-1-55152-304-0

1. Hunter, Robert, 1941 Journeys. 2. Keziere, Robert Journeys.

3. Greenpeace (Boat) 4. Greenpeace Foundation History. I. Keziere, Robert

II. Title.

GE195.H86 2004 333.72 C2004-902955-X

For Alex, Chaz, Dexter, and Rhys

who got to be born

We were so busy preparing to go to the moon

that we were completely unprepared for the

impact the trip would have on our lives.

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin,

February 27, 1972

Contents

BEFORE

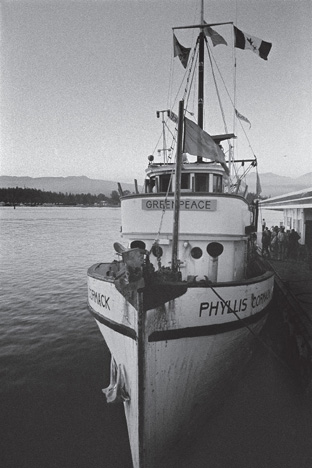

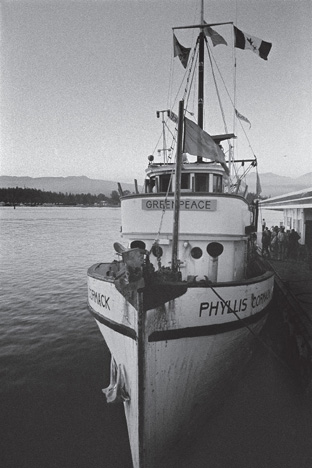

The Phyllis Cormack/Greenpeace departs Vancouver on September 15, 1971.

J UNE 2004

Greenpeace was a product of the Vietnam War, as much as anything. The precursor to Greenpeace, the Dont Make a Wave Committee, was founded in 1970, at a time when no issue could stir up a crowd in Vancouver like Nam. The city was sheltering the largest American expatriate crowd in the world, resolutely anti-war to the last love child among them. This was a generation ago, back when TV showed the boys coming home from Southeast Asia in body bags, the after-image of Woodstock was still burned into the publics retina, the last of the Black Panthers were being gunned down, the Eagle had just landed on the moon, some 56,000 nuclear warheads were ready to be fired, a senility case ruled the Kremlin, and Richard Nixon was on speed in the White House. If you werent paranoid, you were crazy.

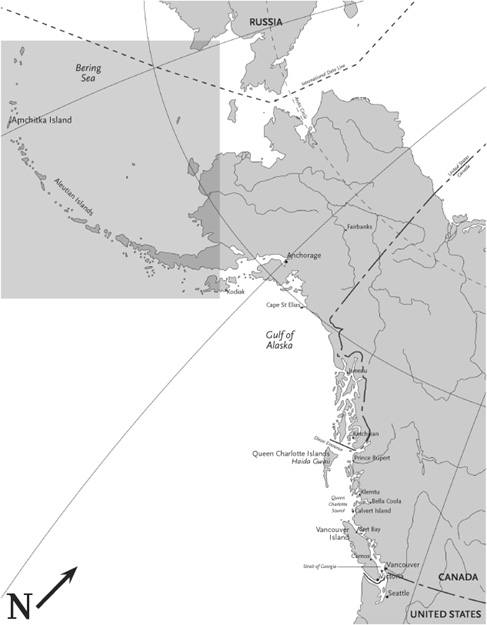

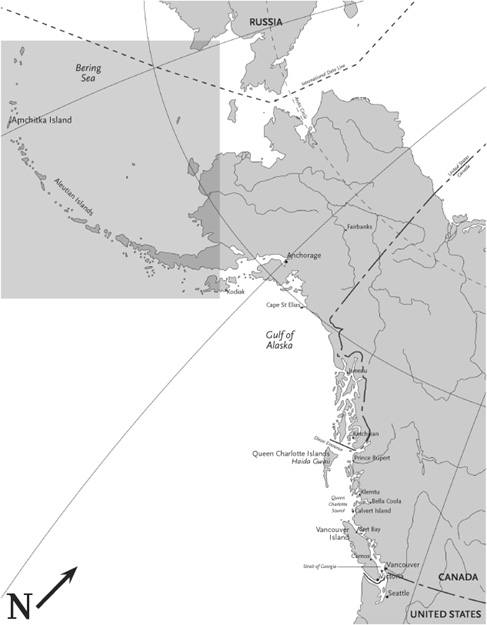

In fact, the protest against the War was the countercultures big-crowd ticket to media glory, having surpassed even Civil Rights as a cause clbre, although the gunshots that took the lives of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy were still echoing in our ears. The ecology movement, then known as conservationism, was a weak cousin of The Movement, as the hundreds of anti-establishment groups collectively were called, but the conservationists had also kept themselves apart deliberately. More than a few of them looked upon the American action in Vietnam with favour, and historically, such wonders as national parks had been a Republican cause. The organizers of the Dont Make a Wave Committee were Jim Bohlen and Irving Stowe, two expat Americans who had fled to Canada so their sons wouldnt be drafted, and Paul Cote, a Canadian law student. They tried to interest the U.S.-dominated Sierra Club in a protest against American nuclear testing in the Aleutian Islands, but the head office in San Francisco said no.

Thus, by default, the new group started off Canadian, incorporated under the British Columbia Societies Act a move that turned out to be brilliant. If the committee hadnt started off in this particular country, it would never have evolved into Greenpeace, a powerful organization of international stature. If the Americans had owned it, theyd never have let it go. Ditto for the Brits, French, and Germans, who now dominate Greenpeace. Only Canucks were liberated enough from nationalism to give it away but that story unfolded long after the first voyage to Amchitka, which none of us imagined would have a sequel, let alone lead to the formation of an eco-navy, complete with a bureaucracy and a political arm, capable (sometimes) of stopping whole megaprojects, fighting such post-space-age nightmares as ozone depletion, genetically modified food, and climate change.

Ninety percent of history is being there, and Vancouver was the only place in the world where a political entity such as Greenpeace could have been born. We had a critical mass of Americans who were really angry with their government. We had the right legal stuff, with sovereignty and anti-piracy rules on our side. We had the biggest concentration of tree-huggers, radicalized students, garbage-dump stoppers, shit-disturbing unionists, freeway fighters, pot smokers and growers, aging Trotskyites, condo killers, farmland savers, fish preservationists, animal rights activists, back-to-the-landers, vegetarians, nudists, Buddhists, and anti-spraying, anti-pollution marchers and picketers in the country, per capita, in the world. If they could be mobilized en masse alongside The Movements long-haired peacenik hordes ah, well, we would be talking about a revolution, wouldnt we? John Lennons Imagine played mightily in the background, but Bob Dylan warned: dont follow leaders and watch the parking meters. What was sorely needed was a coherent vision, a philosophy that could embrace them all. From the moment the word Greenpeace was first uttered in public, we had it or we thought we did. Ban the bomb and save the redwoods! Nukes harm trees! At least it was a good start.

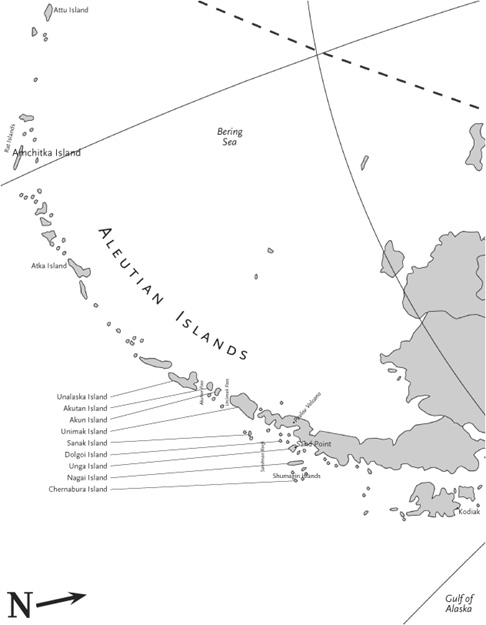

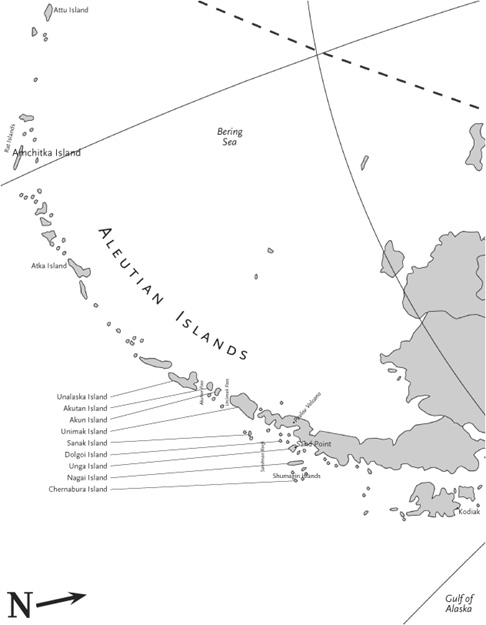

Vancouver was the nearest major city to the test zone at Amchitka Island, Alaska, which made it part of the front line, even if it was protected by Vancouver Island from any tidal waves that might be triggered by the blast. Earthquakes were also a possibility the fault line leading to San Andreas passed within miles of Amchitka. These dangers spoke to peoples very sense of territory. Nowhere else did the general population feel as threatened, and so nowhere else was the story as big. There was a high level of awareness among British Columbians that could be drawn upon like an aquifer, and that sustained Greenpeace through its formative years.

On September 15, 1971, the Dont Make a Wave Committee sent the eighty-foot halibut seiner Phyllis Cormack, temporarily renamed the Greenpeace, to Amchitka. Twelve men were aboard John Cormack, the captain; Dave Birmingham, the engineer; and ten eco-freaks ranging in age from twenty-four to fifty-two and along the way we picked up one more crew member. I have heard our trip described as an odyssey, and so it was, in the modern sense. But in the Homeric sense, it wasnt. The

Next page