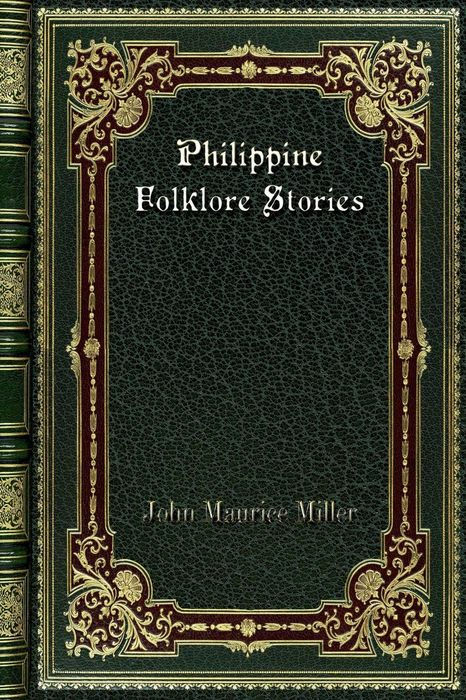

John Maurice Miller - Philippine Folklore Stories

Here you can read online John Maurice Miller - Philippine Folklore Stories full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1904, publisher: Ginn, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Philippine Folklore Stories

- Author:

- Publisher:Ginn

- Genre:

- Year:1904

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Philippine Folklore Stories: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Philippine Folklore Stories" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Philippine Folklore Stories — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Philippine Folklore Stories" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

John Maurice Miller,

Boston, U.S.A.

The Pericos

Quicoy and the Ongloc

The Passing of Loku

The Light of the Fly

Mangita and Larina

How the World Was Made

The Silver Shower

The Faithlessness of Sinogo

Catalina of Dumaguete

The Fall of Polobolac

The Escape of Juanita

The Anting-Anting of Manuelito

When the Lilies Return

That hangs on the wall

Sits a queer-looking bird

That in words sounds his call.

From daybreak to twilight

His cry he repeats,

Resting only whenever

He drinks or he eats.

He never grows weary,

Hear! There he goes now!

"Comusta pari?

Pericos tao."

You can hear this strange cry:

"How are you, father?

A parrot-man I."

He sits on his perch,

In his little white cap,

And pecks at your hand

If the cage door you tap.

Now give him some seeds,

Hear him say with a bow,

"Comusta pari?

Pericos tao."

How hard it must be

To sit there in prison

And never be free!

I'll give you a mango,

And teach you to say

"Thank you," and "Yes, sir,"

And also "Good day."

You'll find English as easy

As what you say now,

"Comusta pari?

Pericos tao."

And "How do you do?"

Or "I am well, thank you,"

And "How are you too?"

"Polly is hungry" or

"It's a fine day."

These and much more

I am sure you could say.

But now I must go,

So say with your bow,

"Comusta pari?

Pericos tao."

Fly in through the door.

Catch Quicoy and eat him,

He is mine no more."

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Philippine Folklore Stories»

Look at similar books to Philippine Folklore Stories. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Philippine Folklore Stories and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.