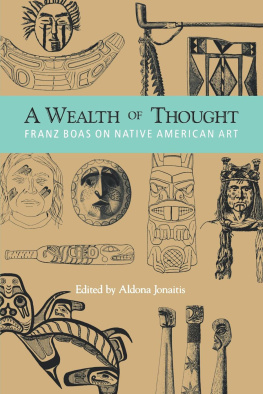

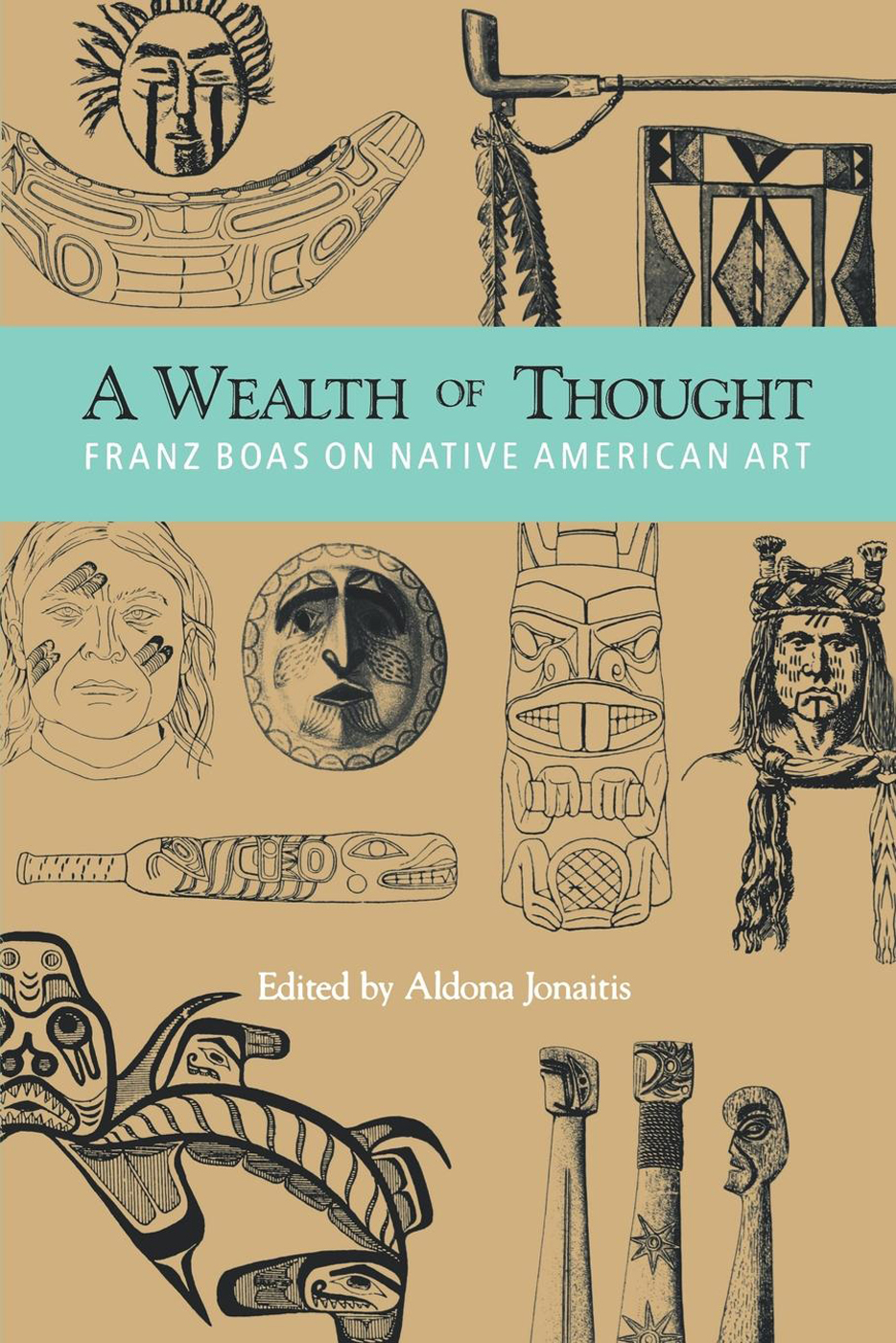

A Wealth of Thought

Franz Boas on Native American Art

A WEALTH OF THOUGHT

FRANZ BOAS ON NATIVE AMERICAN ART

Edited by Aldona Jonaitis

University of Washington Press

Seattle and London

Douglas & McIntyre

Vancouver/Toronto

Copyright 1995 by the University of Washington Press

95 96 97 98 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

Design by Corinna Campbell

Composition by Wilsted & Taylor

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press

PO Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98145

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A wealth of thought : Franz Boas on Native American art / edited by Aldona Jonaitis.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-295-97325-0 (cloth). ISBN 0-295-97384-6 (pbk.)

1. Indian artNorthwest Coast of North America.2. Indian art.3. Art, Primitive.I. Boas, Franz, 18581942.II. Jonaitis, Aldona, 1948.

E78.N78W43 1994

704.03979dc20

94-15180

CIP

Published simultaneously in Canada by Douglas & McIntyre, 1615 Venables Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V5L 2H1

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Boas, Franz, 18581942

A wealth of thought

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-55054-180-3

1. Indian artNorthwest coast of North America.2. Art, PrimitiveNorthwest coast of North America.I. Jonaitis, Aldona, 1948.II. Title.

E78.N78B62 1994709.01109795C94-910583-X

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

My fancy was first struck by the flight of imagination exhibited in the works of art of the British Columbians. I divined what a wealth of thought lay hidden behind the grotesque masks and the elaborately decorated utensils of these tribes.

Franz Boas, The Kwakiutl of Vancouver Island

Contents

Aldona Jonaitis

Aldona Jonaitis

Preface

Welcome!

Greetings! O people of all tribes.

Our thanks that we have come together in this great house.

Our thanks that we have come to view the regalia of our predecessors, the works of our past chiefs.

And, so we have come here to gather, O people of all tribes.

So that we can come to look.

You are proud, O chiefyou are proud of the treasures of your ancestors, of those things that we have come to see in this great house.

I have said it!

I have said it, O chiefs.

Why should we not be proud of these things for they have been saved so that we can see them.

That is it!

That is it! O people of all tribes.

Speech in Kwakwala by Adam Dick, translated by Bobby Joseph, a recording of which welcomed visitors to the American Museum of Natural Historys exhibition Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch.

I n October 1991 a new exhibit opened at the American Museum of Natural History. Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch featured the artworks that George Hunt had collected for Franz Boas at the turn of the century. At the opening, two great-grandsons of George Hunt, Bill Cranmer and Tony Hunt, stood before a crowd of hundreds of staff and visitors and proudly voiced the sentiments expressed earlier by Adam Dick in his welcoming speech.

This opening ceremony was by any definition an historic moment. More than forty Kwakwakawakw from Vancouver Island had traveled to New York City to validate an exhibition celebrating their ongoing artistic and ceremonial traditions.spoke warmly of their continued relationships with the Kwakwakawakw whose culture had dazzled their distinguished ancestor and continues to dazzle later generations.

I sat listening to the speeches, wondering what Boas would have thought had he been present. As his letters reveal clearly, he had a great love for these people whose culture he feared was about to disappear. He was especially fond of George Hunt, a gentle, quiet man whose brilliance has never been adequately acknowledged. Here, in the museum where Boas had worked for ten years trying to record for posterity the complex nature of Kwakwakawakw culture, were descendants of his Native friends, as well as two people he had known personally, Agnes Hunt Cranmer and William Hunt, who praised his efforts and honored his legacy. A man of immense social conscience and personal integrity, Boas had produced a vast body of scholarship informed by a commitment to prove the equality of all human beings and to encourage respect for and understanding of different traditions. Had his ghost been present in the museums Hall of Ocean Life where the opening ceremony was taking place, he would, I think, have been pleased. The people of New York City finally had the opportunity to observe the truth of his premise that all cultures and their material manifestations are worthy of admiration and esteem.

My first encounter with Boas came when I was in graduate school in the 1970s and read his lengthyseemingly endlessdescriptions of Kwakwakawakw art and culture. For someone intent on obtaining the truth about a topic, Boas was, frankly, frustrating. He provided abundant information, but never seemed to tie it up with a conceptualizing ribbon into a neat package that would enable me to understand the baroque art of the Kwakwakawakw. Moreover, his book Primitive Art (1927) seemed to me obscure, tedious, and of limited usefulness for my academic investigations.

Later, while researching a book on the American Museum of Natural Historys Northwest Coast Indian art collection (Jonaitis 1988a), I read his correspondences with George Hunt, John Swanton, and others and discovered behind all the scholarship a passionate, sympathetic, very real man. These letters and the wealth of materials on the Kwakwakawakw that Boas and Hunt left in the American Museums archives then became the source for documenting the artworks exhibited in Chiefly Feasts.of the Kwakwakawakw, for his untiring activities aimed at collecting Kwakwakawakw art and artifacts, and for the social commitment that informed all of his anthropological endeavors.

This is a timely moment to evaluate Boass contributions to primitive art, for many of the points he makes correspond to concepts put forth by the so-called new art historians who reject the hegemony of western art styles, the isolation of art history from economic and social history, and the hierarchical and elitist divisions between high and popular art.

Decolonization and the efforts of Native people around the globe to control their historical representation and cultural property have inspired a rethinking of the anthropologists role. Contemporary critical theorists tend to reject classics and canons, which they view as embodiments of entrenched, male, Euro-American power and thus impediments to the liberation of previously stifled voices. To make room for these new voices, it is often necessary to dethrone old authorities. It would be easy to consider Boas, often called the father of American anthropology, as a prime candidate for such dismissal. Indeed, some of what he wrote deserves critical analysis; however, a careful reading of his work on Native American art suggests that we take a more nuanced view. I propose that in the writings included in this volume, premised as they are on a resistance to premature theoretical closure and an egalitarian ideology, Boas created the space that Native people could ultimately occupy to assert their own voice.

Next page