Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Maya Robinson Waldstreicher,

Moses Henry Waldstreicher,

and their new world

The term black was used relatively infrequently in late eighteenth-century Anglo-America. Negro, which is no longer used in contemporary English, was used at least as often. Neither term was capitalized, even though many nouns and adjectives were (inconsistently) capitalized.

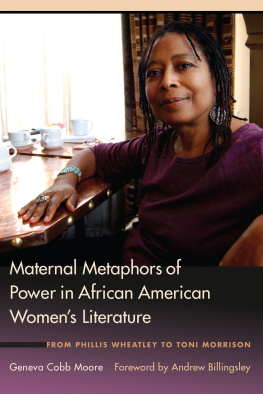

In her poems and letters, Phillis Wheatley employed neither of these terms, both of which had negative and stereotypical implications when used by those who increasingly called themselves white. She regularly used African in referring to herself and others, and sometimes the less common word sable to refer to skin color, as a modifier for race, which she used to refer to nations more often than phenotypes. Wheatley preferred African and sable for political reasons: their use over and against black or negro pushed back against a rising tide of racism in her lifetime. In other words, she used African for some of the reasons that many today value and capitalize the term Black.

In deference to Wheatley, and to call attention to the changing and politicized signifiers of identity to which Wheatley responded, I use black sparingly, in reference to how Wheatleys white contemporaries described Africans and their descendants or when it is clear I mean those people for whom we now use black or Black retrospectively, and do not capitalize. But when I am referring to nineteenth-, twentieth-, and twenty-first-century persons who identified as Black and used the term when referring to themselves and/or to Wheatley, as in the last chapter of the book, I then capitalize.

Everyone around Boston knew about the storm at the end of August 1767. They knew what could happen in gales on the back of Cape Cod. Still, even after years in the coastal trade, the Nantucket merchants Hussey and Coffin had rarely felt such winds. By the grace of God, their schooner and their whale oil had made it safely to a Boston wharf, and they had returned to the fine house of their fellow trader John Wheatley.

The girl came with bowls, with bread. She did not sit at the table, but she listened.

The Wheatleys already knew about her ear. The girl had some sort of gift. Johns wife, Susanna, and their daughter, eighteen-year-old Mary, who had a twin brother but no living sisters, had taught her to read English. It wasnt hard. Soon after they purchased her off the slave ship Phillis in 1761, they had noticed her endeavoring to make letters upon the wall with a piece of chalk or charcoal. Four years later the twelve-year-old penned an impressive letter to a Mohegan missionary who had stayed in their home. She had also written elegies about the deaths of respected men and verse appeals to lapsed Christians that the Wheatleys showed to their friends and neighbors.

The poem Phillis began to write soon after that dinner, the first she published, addressed the near wreck and the Nantucket merchants. The occasion was standard stuff, especially in Massachusetts. Almost half a century earlier an even younger Bostonian, the twelve-year-old apprentice named Benjamin Franklin, had published a ballad broadside about a capsized rowboat and the drowning of a family and their enslaved man. Less conventionally, Phillis addressed Hussey and Coffin directly in her poem. She asks rhetorical questions about their peril: Did Fear and Danger so perplex your Mind, / As made you fearful of the Whistling Wind? Its not a dialogue: she doesnt quote their answers. She speaks of them, about them, to some larger purpose. They may be the subjects, along with the awesome elements, but the voice is clearly hers.

It isnt hard to imagine why the survivor of a slave ship could identify with another terrifying voyage, with voyagers who wondered whether the punishing winds were themselves alive (Was it not Boreas knit his angry Brow / Against you?) and whether the stormy emotions of gods would doom or deliver, save or destroy. But enslaved girls were not encouraged to speak of those voyages. She begins riskily, then, as well as suddenly, in the gales and the waves, throwing us into the action aboard the boat: How did these older men, these merchants, feel? She invokes fear twice. Did they fear so much that even the wind seemed alive? Or, as experienced shippers, did their Consideration, a double entendre meaning both thought and money, enable them to stay calm, to rationalize how the winds, like God, give as well as take?

Apparently not. Or it isnt for her to speculate on merchantmens considerations. She returns to the trope of threatening deities: another wind god, Aeolus, was angry, haughty, frowning. She backs off: she depersonalizes, in a classical idiom that to modern readers has seemed so off-putting, so scholastic, so white. She reaches back to maritime cultures of the Greeks and Romans and the most popular of the neoclassical texts translated by the most ambitious English poets of the previous two generations.

Her first readers in print, in The Newport Mercury of December 21, 1767, and The Boston Post-Boy three weeks later, would have understood instantly. These lines are literally evocative of Homers Odyssey and Virgils Aeneid in their popular English versions. The Odyssey begins with a call to the muses to sing of Odysseuss unnumberd toils on stormy seas. In Alexander Popes translation, the ghost of Agamemnon asks similar questions to the ghost of Amphimedon, one of the suitors slain by Odysseus: What cause compelld so many, and so gay, / To tread the downward, melancholy way? did the rage of stormy Neptune sweep / Your lives at once, and whelm beneath the deep? The storm-tossed voyages in Homer are also accompanied by questions about the gods intentions.

Greeks, Romans, Britons, Africans. Can they be similar? What might this mean? Did she mean it literallydid she believe in these gods of the sea, like a pagan, an ancient? Phillis Wheatley could be talking about herself, imagining herself into the world of the poemas storm-tossed victim or hero, as voice of the dead, as vessel of the gods. More important, she takes control of the references, the presence of the ancient, for the reader of the newspaper who could not have missed that the poem had been written by a Negro Girl. The preface stresses her race. The poem itself places Africa, and her, in a shared ancient world that is at once past and present, a place where even she can speak with authority.

The boldness of address, the claim to share the ancient world on equal terms, is hidden by the seeming imitation, the classical references. But not enoughnot nearly. Having established her classical propers, Phillis switches registers. The pagan deities are a metaphor: Regard them not. A Christian salvation is at stake. If Hussey and Coffin had perished in the sea, where woud they go? where woud be their Abode? / With the supreme and independent God, / Or made their Beds down in the Shades below? Christians and Africans, like ancient Mediterraneans, believed in another world where the dead reside. They also equally believed in revelations. The poetic narrative returns to another tradition, at once classical and Christian, and especially important in early modern Western Christendom: the good death, to be preferred to the godless life full of fear. Are they saved? Are they going downor up?