The Tonga Book

February 1805 June 1811

The remarkable adventures of young William Mariner ona voyage around the world and his long sojourn in the islands ofTonga wherein he gives us a full account of the inhabitants ofthose islands and the conduct of their lives.

Fourth Edition

By Paul W. Dale

Smashwords ebook edition published by FideliPublising, Inc.

Copyright 2011, Paul W. Dale

No part of this eBook may be reproduced or shared byany electronic or mechanical means, including but not limited toprinting, file sharing, and email, without prior written permissionfrom Fideli Publishing.

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoymentonly. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people.If you would like to share this book with another person, pleasepurchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. Ifyoure reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was notpurchased for your use only, then you should return toSmashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respectingthe hard work of this author.

ISBN: 978-1-60414-418-5

Text taken from the original book by Dr. John Martinand Mr. William Mariner published in 1817 is set in this typeface.The remarks, explanations, and annotations of the author are set inbrackets, [ ], or in separate paragraphs in italics.

Chapter One The Voyage Out

February 12, 1805 November 29, 1806

My name is William Mariner. My father, MagnusMariner, was owner and commander of an armed merchant ship underLord Cornwallis in the rebellion of our American Colonies. Early inthese voyages to the New World he achieved some measure offinancial success; but toward the end of that war, he suffered suchlosses that he abandoned seafaring in favor of marriage and acomfortable life in London where I was born in September, 1791.

It was as a lad of thirteen years that I firstwent to sea in the capacity of captains clerk on board theprivateer, the Port au Prince . Myeducation at Mr. Mitchels Academy at Ware in Hertfordshire wellsuited me for that position. In the few years I attended there (cutshort by the schoolmasters untimely demise) gave me knowledge ofhistory, geography, the French language, a little Latin, and goodfacility in reading, writing, and calculating.

Mr. Duck, Captain of a privateer, the Port au Prince , formerly served hisnaval apprenticeship under my father and their robust conversationsin our home putting forward their visions of the great success ofthe forthcoming voyage led me to plead with them to go along,although mother was much against it. I had, in the preceding sixmonths, been apprenticed to a lawyer; but going to sea, as myfather had once done, seemed much to be preferred over clerking ina law office. My eagerness was heeded. Captain Duck took me underhis protection and created for me the position of his clerk. I wasthusly apprenticed to my fathers former apprentice. In due courseI stationed myself on board the Port auPrince in the harbor at Gravesend.

The Port au Prince was originally a French ship: she was taken as a war prize byEnglish forces near the Caribbean port of the island of Hispaniolawhose name she now bore. Her listing can be found in LloydsRegister of Shipping for the year 1805. At the time I went on boardshe was fifteen years old. Her draft was eighteen feet and she wassheathed in copper as protection against worms and other marinegrowth. The letter of marque from the King was dated January 23,1805. The Kings license was to take ships and possessions of theSpanish. England was now at war with France. Spain, under coercionfrom Napoleon, was an ally of France and thus became subject tohostile action by British privateers. The system of privateeringgave the King of England an addition to his naval forces at noexpense to the Crown. One-third of our crew had to be landsmen toreduce the drain on English sea-going manpower.

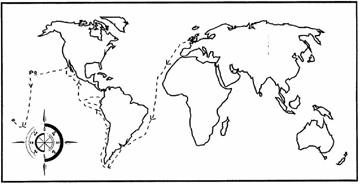

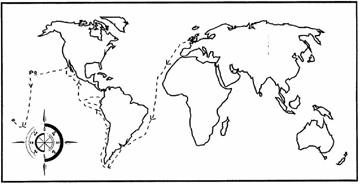

Map 1.Chart of the voyage of the Port auPrince. Credit: Authors collection.

The Port au Prince was fitted out with heavy guns and other armaments for attackupon the Spanish, and she also carried all the necessary equipmentfor whaling. It is uncommon for a privateer, a piratical sort ofship, licensed by our King to raid South American coastal villagesand the shipping of his Catholic Majesty, the King of Spain, to gowhaling; but the Captain of the Port auPrince , thought there could be as much profit in whalingas in privateering. For a privateer to be fitted out for whaling,as was our ship, was indeed unusual.

We sailed from Gravesend on the morning of February12, 1805. What with equatorial calms and then gales in the southernhemisphere the ship did not reach the Atlantic coast of SouthAmerica until early May. By the 17th of June Cape Hoorne was viewedahead, that last small bit of land at the south end of the Americancontinent; but it was not until the 26th of June that we doubledthat Cape. Unfortunately it was now mid-winter in these latitudes,we were much bothered by snow above decks and troublesome leaks ofice water through the hull below.

Our first action against the Spanish occurred nearthe end of July when we reached the port of Concepcion [Chile] andattempted to cut out two English whalers detained by the Spanish;but their cannon fire forced us to withdraw. We continued northwardalong the coast and had some success in less defended places andagainst less armed vessels, losing only a few of the ships companyto hostile gunfire. We took on board many Spanish dollars and muchsilver plate. For the next twelve months we were thus engaged andthen moved off the coast to the equatorial whaling grounds.

Our dear Captain died of an illness in August,1806 while on the whaling grounds near the island of Cedros whichlies off the coast of Baja California and he was buried on thatisland. Our leaking ship now required us to pump seventeen feet ofbilge water every day. Our new commander, Mr. Brown, resolved thatwe should make for the HawaiiIslands to refit, repair, and provision.

We spent a month from the 28th of September tothe 26th of October in the HawaiiIslands at the harbor of Honolulu repairing our rotting ship andloading a plentiful stock of hogs, fowls, plantains (bananas),sweet potatoes, taro, and other food stuffs.

While our ship lay at anchor, many of the Hawaiianchiefs visited us on board as well as some of the Europeans andAmericans who now resided here, numbering ninety-four persons. Irecall a conversation in the captains cabin when the King, a mancalled Kamehameha, when questioned about religion in his islands,he replied saying, I should be afraid to adopt so dangerous anexpedient as Christianity; for I think no Christian king can governin the absolute manner in which I do, and yet be loved by hissubjects as I am by mine. Such a religion might perhaps answer verywell in the course of a few generations; but what chief wouldsanction it in the beginning, with the risk of its subverting hisown power, and involving the islands in war? I have made a fixeddetermination not to suffer it.

We were well treated by the natives of these islandsand eight of their number agreed to sail with us as we were by thistime in need of additional crew. Also, a Scotsman, a Botany Bayconvict, now residing on Oahu, entrusted his half-Hawaiian,two-year old son to the care of our sail maker that he might betaken to relatives in Scotland and there be educated.

Captain Brown set upon heading for Tahiti but thewinds and currents drove us too far west to lay those islands soour course was changed to Tonga, those islands much visited by thelate Captain James Cook and named by him the Friendly Islands.Here, in these hospitable islands, so well spoken of by that famousexplorer who resided three months among the Tonga Islands in 1777,Mr. Brown hoped to again make repairs sufficient for us to reachthe British colony in Australia; for our ship had begun once moreto take on water so badly we needed to pump one-half hour of everytwo.