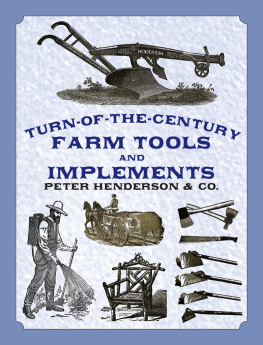

TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY

FARM TOOLS

AND

IMPLEMENTS

PETER HENDERSON & CO.

With a New Introduction by

Victor M. Linoff

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

MINEOLA, NEW YORK

Copyright

Copyright 2002 by Dover Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2002, is an unabridged republication of the Catalogue of Tools and Implements, Fertilizers, Insecticides and Essentials... originally published by Peter Henderson & Co., New York, 1898. A new introduction has been specially prepared for this edition.

DOVER Pictorial Archive SERIES

This book belongs to the Dover Pictorial Archive Series. You may use the designs and illustrations for graphics and crafts applications, free and without special permission, provided that you include no more than ten in the same publication or project. (For permission for additional use, please write to Permissions Department, Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501.)

However, republication or reproduction of any illustration by any other graphic service, whether it be in a book or in any other design resource, is strictly prohibited.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Catalogue of tools and implements, fertilizers, insecticides, and essentials.

Turn of the century farm tools and implements / Peter Henderson & Co.

p. cm. (Dover pictorial archive series)

Originally published: Catalogue of tools and implements, fertilizers, insecticides, and essentials. New York : P. Henderson, 1898. With a new introd.

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-42114-8 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-486-42114-7 (pbk.)

1. Agricultural implementsUnited StatesCatalogs. 2. Farm equipmentUnited StatesCatalogs. I. Peter Henderson & Co. II. Title. III. Series.

S676.3 .C38 2002

631.3dc21

2002024730

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

42114704

www.doverpublications.com

INTRODUCTION

By Victor M. Linoff

The Garden

While the origins of gardening are shrouded in history, growing flowers, fruits, and vegetables is an ancient activity, one that no doubt dates back to the time when man turned from a nomadic hunting and gathering way of life to staying in one place and cultivating his own food. As life became more settled, the ability to produce a steady supply of food by sowing crops enabled humans to pursue less strictly utilitarian endeavors. So it was that gardening came to include both the practical and the ornamental.

As the centuries passed, gardening continued to grow in popularity, resulting in the development of a literature of gardening. In fact, writings on the subject date back at least as far as the sixteenth century. By the nineteenth century, gardening had become an integral part of Victorian life. Books and periodicals proliferated, offering the latest information, trends, and advice about all manner of gardens and crafts.

When the Henderson Company Catalogue was published in 1898, gardening had evolved into a multifaceted activity: social, recreational, and commercial. For many, market and/or truck gardening was either a livelihood or an additional source of income. Others merely gardened for pleasure. Recreational and ornamental gardening was no longer the exclusive prerogative of the wealthy; people of all classes and in all situations were actively gardening for pleasure and fun.

In addition to sheer beauty, gardens provided fruits and vegetables, herbal medicines and spices, and an abundant supply of fresh cut and aromatic flowers for decorating the home. In urban settings where outdoor gardens werent generally possible, window planter boxes were frequently used. Larger homes often featured greenhouses and conservatories. The nineteenth century was an era of great ingenuity and diverse attempts to bring the glory of nature indoors. This penchant for the natural was manifested in many ways. Drying flowers for crafts and art projects was a popular pastime. Floral prints, nature studies, and still lifes of fruit and flowers abounded. Floral and plant motifs were ubiquitous ornamentation on furniture, wallpaper, and other surfaces. In fact, the Art Nouveau style, with its sinuous and luxuriant forms, was the ultimate homage Victorians paid to the beauty of nature.

Gardening on a large scale, i.e. farming, was one of the largest nineteenth-century industries. There were, at the end of 1868, in the United States 2,033,665 farms, comprising 405,280,851 acresan average of 199 acres for each farm. Add to that countless private and commercial urban gardens and its easy to understand why more than 600 U.S. companies offered seeds, tools, implements, and supplies for recreational, market, and truck gardening and farming. Along with the Peter Henderson Company, major firms whose names are still recognized today include the W. Atlee Burpee Company, Ferry & Co., Chas. C. Hart Seed Company, James John Howard Gregory, and James Vick. Large general catalog houses like Sears, Roebuck & Co. and Montgomery Ward were also major providers of materials.

The Man and His Company

During his lifetime Peter Henderson established himself as a leader in the field of horticulture and floriculture. Though never formally trained, the mostly self-taught Henderson became one of the most

The youngest of three children, Peter Henderson was born in 1822 in Pathead, Scotland, a small farming village twelve miles from Edinburgh. His father James, a local land steward, essentially raised him after his mother Agnes died when Peter was eight. Moreover, though he died twelve years before Hendersons birth, it is speculated that his maternal grandfather (Peter Gilchrist, 17401810) was a major influence on the young mans choice of career. Gilchrist had been a respected nurseryman and florist, whose collection of horticultural writings and other materials undoubtedly came to the attention of the budding gardener.

From age sixteen to twenty, Henderson was apprenticed to George Sterling, head gardener at Melville Castle near Dalkeith. Young Peter showed a real interest in, and proclivity for his work. Sterling saw a special gift in his apprentice and as a mentor became a powerful influence in his life. After just one year under Sterlings tutelage, Henderson competed for and won the first of many awards, a medal from the Royal Botanical Society of Edinburgh for the best herbarium of native and exotic plants.

At age 21, apparently following in the path of his brother, James, Peter Henderson emigrated to the United States in 1843. He immediately began working in nurseries; first in Astoria, Long Island, and then in Philadelphia where he was employed by Robert Buist, Sr., a leading nurseryman of the day. That experience led to employment as a private gardener in Pittsburgh.

By 1847, the resourceful 25-year-old had saved $500enough to form a partnership with his brother James in Jersey City, New Jersey. Together they worked on a rented ten-acre plot with three small greenhouses. Several years later James went off on his own to concentrate on vegetable gardening. Peter Henderson continued at the Jersey City site until 1864. Over time he had acquired about ten acres a mile away in South Bergen. On this land Henderson erected what was at the time considered a model range of greenhouses, heated and ventilated in the best known methods then in vogue. )

On the personal front, Henderson met and married Emily Gibbons, a native of England, in 1851. Together they raised two sons and a daughter. Three years after Emilys untimely death in 1868 at age 34, Henderson remarried. His second wife, Jean Reid, was the daughter of his friend and former partner, Andrew Reid. She survived Hendersons passing in 1890.

Next page