IN THE FRONT LINE

This eBook edition published in 2013 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright the Estate of Alec Glen, 2013

The moral right of Alec Glen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by his Estate in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher

ISBN: 978-1-78027-130-9

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-612-0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Plates

Maps

The Story of the Manuscript

This book was written primarily for Alec Glens children and grandchildren between 1965 and 1970.

His two sons, my brother Iain and I, had both left home and were busy with work and young families at this time. When either of us looked in to see the folks at home we found Alec busy on an old portable typewriter, something new for him. To our enquiries, we were both given the reply, I am writing about my experiences. You will see it when its finished..

Rather surprisingly, neither of us was shown a draft typescript, and when we asked about progress, we were told, I am still working on it. Later we heard that one or other of his friends had it to read.

I do remember that my brother persuaded him to see Richard Attenboroughs film Oh What a Lovely War, which was released in 1969. We liked it as a film, but it was not a favourite with Alec, who said, It was not like that at all. Looking back on this now I am inclined to think that he thought it might be better that we read his story when we were a bit older and hopefully wiser.

The manuscript disappeared from our thoughts until 1984 when our mother died, twelve years after her husband. The much-annotated manuscript in its black binder was there with my fathers papers, along with a caricature of him drawn by Osborne Mavor in Mesopotamia. The manuscript was copied, and we, and later, the next generation, read it. Although the memoir made an impression on us, we knew that it was a very personal account and not a history of the period.

The original manuscript was worn and the copy never very clear and we realised that it could easily become impossible to read. With the possibility of renewed interest in World War I as its centenary approached, my brother and I agreed that if it was ever to be published, now was the time. I telephoned Birlinn and received an encouraging response. Three chapters of faded typescript were sent to Birlinn in 2011.

When we were considering an approach to a publisher with these memoirs, we asked ourselves why they might be of interest to present-day readers. There have been a number of accounts of the campaigns in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia. What could this book add to the understanding of these events.

This is not an account of strategies or campaign politics, nor is it a day-by-day diary of life at the front line; rather it is a very personal reflection on those days in which details flood back of remembered voices: some of them heroes, some unknown and some recognised leaders.

This is the work of a man with a clear view of right and wrong who displays the classic characteristics of the Scot; thrawn, determined if he thought he was right, yet sensitive to what others were thinking and feeling. The memories of highly charged and stressful situations are recalled with remarkable clarity.

The manuscript was converted to electronic form later in 2011, and after minor corrections and editing we bound up an edition for family members to read. Some friends read it also and made favourable comments.

We were greatly encouraged by an email from Dr Iain Macintyre of the Scottish Society of the History of Medicine, who had been contacted by Birlinn for an opinion. He liked the story and suggested that we apply to the Society for grant support towards publication. We were delighted when in August 2012 we agreed a contract with Birlinn for publication, supported by the grant and a contribution from ourselves.

For the published edition explanatory footnotes for the modern reader have been added to the occasional notes which Alec himself made on the text.

Alastair Glen, June 2013.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Hugh Andrew of Birlinn for taking on publication of this book, with particular thanks to Tom Johnstone, managing editor at Birlinn. Toms advice, care and can-do approach have been enormously helpful in making the work ready for publication.

Crucial at an early stage were the encouraging comments made by Dr Iain Macintyre of the Scottish Society of the History of Medicine, which led to a grant towards publication provided by the Guthrie Trust.

Acknowledgement is made with thanks to the family of the late Osborne Mavor (James Bridie) for permission to include several extracts from Mavors writing and plays. A special thanks goes to James Mavor for giving permission to include a 1917 caricature of Alec Glen drawn by Osborne Mavor in wartime Persia.

Alec Glens family were encouraging throughout and it is a pleasure to recall the enthusiastic contributions made by the late professor Iain Glen, Alecs oldest son, who died in February 2013. He saw the book through as far as the formal agreement to publish, and made working on it a happy memory.

The author left no dedication for the book but the reader can guess who he thought were the many worthy characters in his story.

Preface

I have written this book primarily for my children and grandchildren to read.

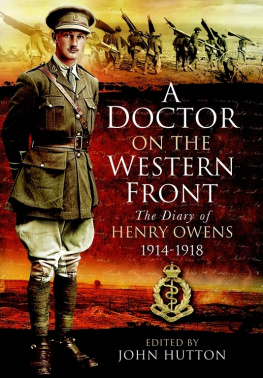

A very large proportion of my generation between the ages of twenty and thirty-five died in the First World War. The tragedy was not only in their numbers. It was the best and most generous-hearted men who died. The medical officers in the front line knew this better than anyone else. Sometimes they survived longer in a battalion than any of the combatant officers.

Were these great wars unnecessary, as many of the younger generation are inclined to think today? I do not feel competent to answer that question and am content to leave it to future historians. I can say, however, that when we resisted the German warlords in the First World War we thought that we were fighting something evil. Nietzsche had taught them that self-reliance, the will for mastery and the cult of personal distinction were the noblest of all the virtues. Humility, compassion, self-sacrifice, as inculcated by Christianity, were virtues of the poor, the oppressed and the suffering. The pursuit of happiness was the ignoble idea of the common herd of mankind. The German warlords had developed a proud consciousness of their own superiority and a lofty acceptance of the self-sacrifice of others. This is what we were fighting against in the First World War. It is not surprising that it was the most terrible of all wars. In the Second World War we all knew that we were fighting against something evil and that made it more understandable.

The second part of this book deals with the aftermath of these two great world wars. During these fifty years we have missed very badly the men who died, and perhaps also we have missed their unborn children. If they had been alive and had been our leaders I think that we might have made a much better job of the years between the wars and since the second war. The men who have ruled us during these years have been mostly unimaginative, ungenerous and not very courageous.