The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1976, 1978 by The University of Chicago

Preface to the Second Edition 2003 by The University of Chicago

Appendix 2003 by Elijah Anderson

All rights reserved. Published 2003

Printed in the United States of America

12 11 10 09 08 3 4 5

ISBN: 0-226-01959-4 (paper)

ISBN: 978-0-226-77502-9 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Anderson, Elijah.

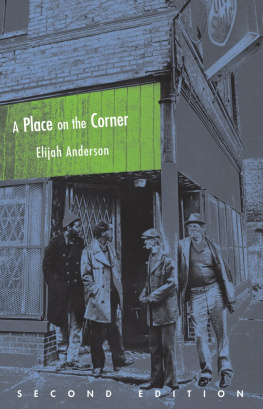

A place on the corner / Elijah Anderson.2nd ed.

p. cm.(Fieldwork encounters and discoveries)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-226-01959-4 (pbk : alk. paper) 1. Small groupsCase studies. 2. Social statusIllinoisChicagoCase studies. 3. Participant observationCase studies. 4. Chicago (Ill.)Social conditionsCase studies. I. Title. II. Series

HM736. A53 2003

302.34dc21 2003048351

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Preface to the Second Edition

When I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago during the 1970s, the emphasis in the sociology department was on quantitative research. Yet, many graduate students were beginning to conduct qualitative studies reminiscent of the Chicago departments early history. Among these young scholars were William Kornblum, whose work was on community and working class life at a South Chicago steel mill; Ruth Horowitz, who studied local gangs; Carole Goodwin, who studied the community of Oak Park, Illinois; Charles Bosk, who studied surgical residents; Tom Guterbock, who worked on machine politics; Mark Jacobs, who studied juvenile probation officers; James Jacobs, who did work on prisons; Michael Burawoy, who studied the political culture of shop floor workers; Andrew Abbott, who studied mental institutions; and David Gordon, who studied a religious movement. And I conducted ethnographic work at a South Side Chicago corner bar and liquor store that came to be known as Jellys.

At the time, Morris Janowitz was trying to revive the old Chicago school through his Center for Social Organizational Studies, which supported Kornblums work, my work, and that of several other students; other centers and faculty were also supportive. Additionally, the students involved with Janowitzs Center would attend regular seminars on topics of social organizational and ethnographic interest, and many were encouraged to read Robert E. Park and Ernest Burgesss The Introduction to the Science of Sociology and other Chicago classics. But at the inspirational core of these qualitative revitalization efforts was Gerald D. Suttles. It was through taking his field methods course that I had the opportunity to pursue ethnographic work and found the setting for A Place on the Corner. Often, Suttles, through his course, not only provided students their first intense fieldwork experience; he also created an intellectual circle that sustained and diffused the research tradition he had embodied in his own work. Moreover, Suttles must have been conscious of his own intellectual role, for his relationship to students transcended instruction, guidance, and critique; it included friendship and personal support. Among those supporting and extending Suttless leadership were such scholars as Victor Lidz, Barry Schwartz, William J. Wilson, Charles Bidwell, Richard Taub, Donald Levine, Terry N. Clark, and William Parrish. These faculty members spent many hours seeking to develop what they hoped would be the leading scholars for the next decade and were especially helpful as teachers and role models.

I worked closely with Suttles for about two and a half years, at which point he left the University of Chicago, leaving what was for me a strongly felt vacancy. Then I moved to Northwestern to work with Howard S. Becker. There I found more support for ethnographic work, including a nurturing community of graduate students and teachers, including Bernie Beck, Charlie Moskos, Ackie Feldman, Arlene Daniels, and Jim Pitts, among others. I continued to work with both Suttles and Becker for the duration of my graduate studies.

In the early part of the century, many sociologists were steeped in the thinking that ghetto areas and urban villages, where so many ethnic, working class, and poor people lived and played, were disorganized, highly dangerous, and in need of social reform. Ironically, the roots of a correctionist approach were planted in the early urban studies of the Chicago school. Later, the related position of social disorganization was challenged by William Whytes Street Corner Society, and further questioned by the example of Herbert Ganss The Urban Villagers.

But the fullest expression of a more complex and socially relativistic perspective was the series of naturalist (Matza 1969) participant-observation studies provided by Howard S. Beckers Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. Gerald D. Suttless The Social Order of the Slum and William Kornblums Blue Collar Community further contributed to the debate by showing lower class neighborhoods and communities to be in fact highly organized in socially complex ways. When I began my work at Jellys, the issue was not completely settled. Thus it seemed reasonable to focus on the issue of social organization and its component partssociability, status, identity, beliefs, and valuesissues that emerged quite naturally at Jellys.

The sociological contribution of A Place on the Corner is really twofold: first, the text presents a set of conceptual findings related to status and social grouping, and second, an ethnographic portrait of men at a particular historical time marginalized by skin color and poverty. These findings grew out of three years of participant observation among a group of roughly fifty-five black street corner men who hung out regularly at Jellys, a street corner bar and liquor store located on the South Side of Chicago. Jellys was their place, a kind of club house where they established and maintained their own social rules and standards of propriety. It was in this setting that they could relax and be themselves, away from the constant gaze of the wider society, white as well as black. Erving Goffman might have referred to the setting as one of remission, or as backstage to society. It was a place where the people of Jellys could hang out, where they knew they mattered to the others present, and where there were people who cared about them and whose opinions of them they regarded. As the men hung out at Jellys, they engaged in the fundamentally human process, utterly front stage, of making and remaking their own local stratification system. During everyday social interaction, the subgroups of the wineheads, hoodlums, and regulars became clarified as their members competed for place and position, their identification with one group or another based on their putative control of resources more or less valued by the general group. In these circumstances, the fundamental outlines of the extended primary group emerged. A product of collective action, status, and rank appeared all the more fluid. Here status existed in and through social interaction, with people moving up or down, depending on what others present thought of them and allowed. In essence, social order existed because people largely stayed in their places, and they did so because other people helped keep them there.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.