First published 2007 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2007 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

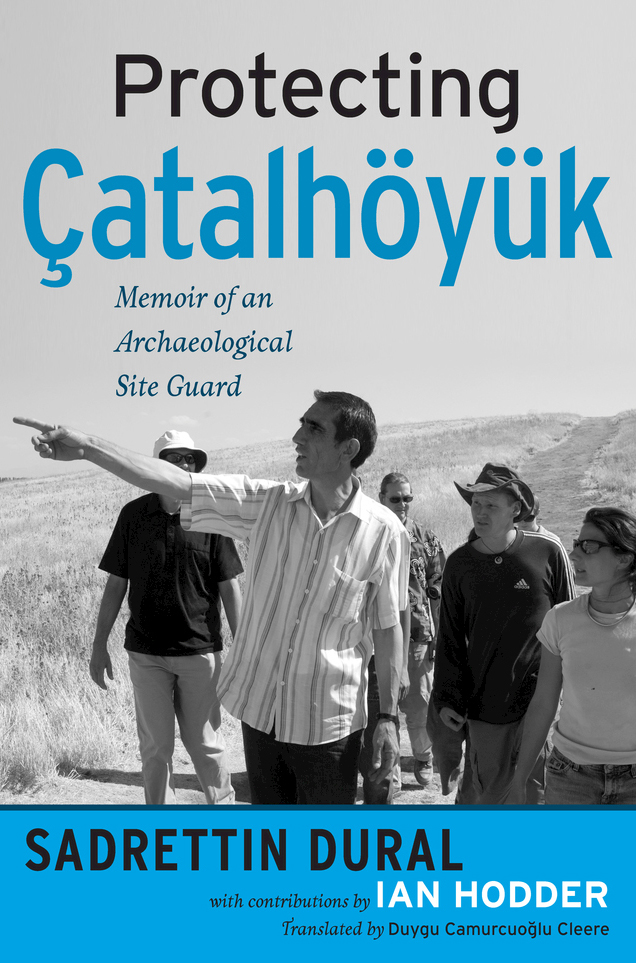

Dural, Sadrettin, 1953

Protecting atalhyk: Memoir of an Archaeological Site Guard /

Sadrettin Dural; with contributions by Ian Hodder; translated by Duygu

Camurcuolu Cleere.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-1-59874-049-3 (hardcover: alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-59874-049-0 (hardcover: alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-1-59874-050-9 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-59874-050-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Dural, Sadrettin, 1953- 2. Private security servicesTurkey

EmployeesBiography. 3. atal Mound (Turkey) I. Hodder, Ian. II.

Title

GN776.32.T9D85 2006

363.28'9092dc22

2006033267

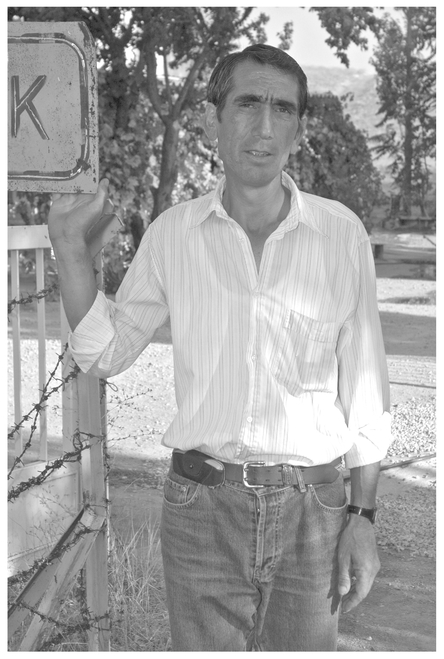

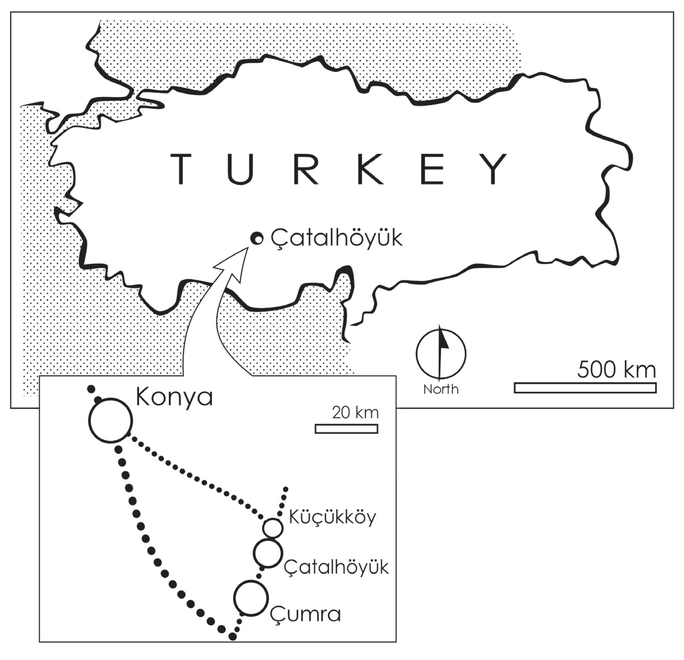

Cover photo and author photo by Jason Quinlan. Maps by John Swogger. Stamp seal drawing by Ali Turkcan. All provided by kind permission of the artists and the atalhyk Project, directed by Ian Hodder.

Typesetting: ibid, northwest

ISBN 13: 978-1-59874-050-9 (pbk)

lan Hodder

I first met Sadrettin at the site of atalhyk. It was our first season in 1993. Sadrettin was ever present as we tried to work out how we could live and organize our lives in the early days. I could understand very little of what he said. My Turkish was very poor, and he spoke in a very fast jumble of words and with a thick local accent. He smiled a lot and made people around him smile. But it was not until much later, when I could speak a bit more Turkish and he had found some tapes to learn English, that I really got to know him and to appreciate his wry view of the world. I taught him about the site so that he could guide people around the site better, and because he just wanted to know. He had this appetite for knowledge. But I also taught him because I wanted to know his slant on what we were doing and how the site might be interpreted.

It seemed wrong that his perspective, his voice, should not be heard. Other villagers were part of the team and took part in our discussions, and their voices are heard in some of our publications (see especially Hodder 2005c). But Sadrettin's role as a guard, having to be ever ready to take a tour around the site, meant that he was on the margins of the research we were doing. And yet he became such a central part of our lives, a real personality in our midst, looking at us from his background in the village.

I was amazed, but pleased, when he said he wanted to write a book. Having seen so many pictures of the "local workforce" adorning the pages of the great archaeological tomes from the Middle East and elsewhere in the world, and yet never having read a word written by these people who made archaeology possible, and who spent sometimes many generations working as field archaeologists or site guides, it seemed important to encourage and help Sadrettin in his venture. He had never used a keyboard before and could not understand why the letters were not in alphabetic ordermany moments of hilarity followed as he poked fun at the insanity of the jumble that he had to learn.

The text that Sadrettin produced was an outpouring of consciousness, but also of fun, anger, and hurt. When I first saw the Turkish text, it was about 50,000 words in sequence with not one paragraph, full stop, comma, or capital letterjust a long stream of words. With the advice of some friends of the project, especially Nurcan Yalman, Ayfer Bartu Candan, and Can Candan, we asked Sadrettin to make some changes to focus more on the site and his time as a guard there. Once he had made these changes, Duygu Camurcuolu Cleere did a quite remarkable job of translation. Sadrettin's text was difficult and unconventional, with many local colloquialisms. She managed to capture his style and wry humor, and in correcting the English I have as far as possible tried not to edit the resulting text. The device of using notes seemed unobtrusive while allowing me to provide some explanation and context for the reader, so as better to understand Sadrettin's meanings.

So at last I began to see what our presence meant to Sadrettin, from his point of view. I saw how we had intruded ourselves into a rich and complex world of knowledge about the landscape and about the ancient mounds that dotted the Konya plain, of which atalhyk is just one of many examples. I saw how wrong it was to say that we as archaeologists had "discovered" these sites, when all we had done was to recognize their significance in terms that made sense to us. I realized more fully how local people became dependent on us, but we were so rarely there for them. We came and went seasonally, extracting what we wanted for ourselves. I understood more clearly the lack of sensitivity that we and tourists bring with us.

I wanted to let Sadrettin write in his own voice, and I have perhaps already said too much. But I do want to thank some people, beyond those already mentioned, for making this book possible. Shahina Farid, as always, gave advice and support. Indeed, the excavation team as a whole has been part of the process whereby Sadrettin felt involved in what we were doing. I also wish to thank Mitch Allen for having the courage and vision to make this book available.

Sadrettin's is not a success story. It does not chart the successful education and empowerment of one of those many who have for so long been overlooked at the edges, but actually at the center, of archaeology. It could hardly be said that Sadrettin's story charts the end of centuries of colonial archaeological manipulation and silencing. His story is at once amusing, uplifting, tragic, and unending. But in providing us with his voice, Sadrettin has opened up new possibilities for dialogue. I have learned a lot from him in terms of how atalhyk might be managed and interpreted, and in terms of how archaeologists might work with local communities. I hope that others, too, will gain from reading his words.