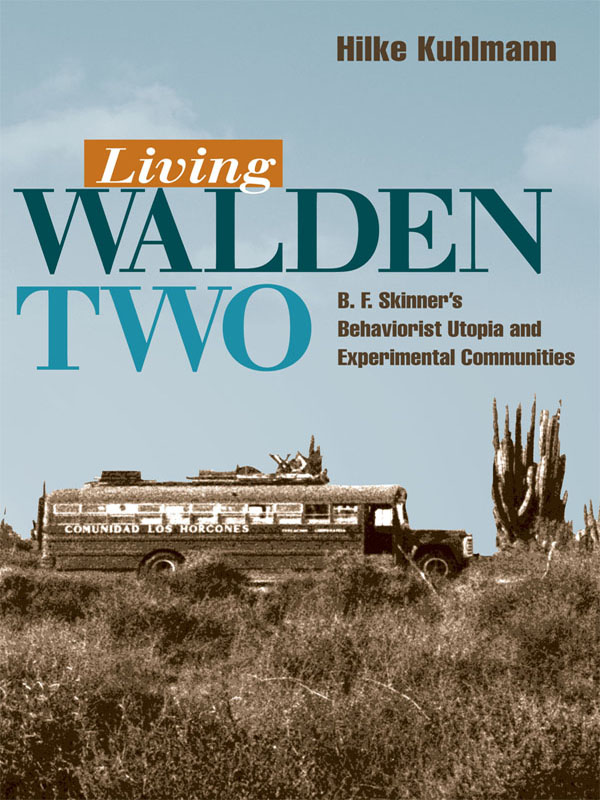

Living Walden Two

Sharing work is an important aspect of daily life at Twin Oaks Community. (Courtesy Twin Oaks Community.)

An old school bus serves as a communal means of transportation on group trips to the beach. (Photo by H. Kuhlmann.)

2005 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

c 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kuhlmann, Hilke, 1969

Living Walden Two : B. F. Skinners behaviorist utopia and experimental communities / Hilke Kuhlmann.

p. m.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-252-02962-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. UtopiasUnited States. 2. Behavior modificationUnited States. 3. Skinner, B. F. (Burrhus Frederic), 1904 Walden two. 4. Communal livingUnited States. I. Title.

HX806.K84 2004

307.77'0973dc22 2004020463

Contents

Acknowledgments

RESEARCHING communal experiments is a lot like poking around in other peoples broken dreams. For this reason, I am particularly grateful to all of the current and former communards who shared their stories with me and often went out of their way to help me. Special thanks go to Twin Oaks Community for opening its home to me and teaching me the art of weaving hammocks, among other things.

On the academic side, I thank my advisor, Manfred Ptz, for first introducing me to Walden Two and seeing me through the Ph.D. process, and Kenneth Roemer and Donald Pitzer for their expert advice and support through all phases of this study. Most importantly, I am deeply grateful to Lyman Tower Sargent for always being there with advice whenever I needed it.

Research on the reception of Walden Two in intentional communities was made possible by a grant from the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) for 1998. My time as a participant-observer at Twin Oaks as well as shorter visits to Los Horcones, Lake Village, Sunflower House, and Dandelion Community deepened my understanding of these communities.

I thank Frank Cass for permission to reprint a modified version of an article that first appeared in the Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 3.23 (Summer/Autumn 2000). I also thank the special collection on communities at the University of Virginia as well as the archive of the Center for Communal Studies in Indiana for opening their doors to me.

Above all, I wish to thank my family and friends for supporting me from the enthusiastic beginning to the exhausting end of this project, be it as listeners, proofreaders, or general support team.

Introduction

B. F. SKINNERS Walden Two is arguably the most influential and hotly debated fictional utopia of the twentieth century. In the early summer of 1945, Skinner envisioned a society finally set free from war, suffering, and personal unhappiness. The psychologists utopian vision as such was not unique, but his proposed technique for achieving the good life was: drawing on his laboratory experiments with rats and pigeons, Skinner thought that to change society effectively one had to change human behavior itself. To do this he suggested employing the techniques of behavioral engineering.

Although Skinner had done research almost exclusively on animal behavior at the time he wrote Walden Two, he was confident that the startling results his studies had produced in this area could also be applied to humans. Skinners experiments suggested to him that animal and human behavior is always dependent on outward influences and that, contrary to popular belief, positive reinforcement is much more effective in handling behavior than punitive control, with its destructive side effects. Therefore, the perfect society should make extensive use of positive reinforcement in all areas of life. This led him to envision a society designed by behavioral engineers, who would condition people to live and enjoy the good life while being freed of such emotions as aggression, jealousy, or competition.

Whereas Skinner was convinced that he had found the key to world peace and happiness, almost nobody else seemed to think so in 1948, when the novel was first published. Far from being praised or even debated, the book was simply ignored. Walden Two only began to sell more than a dozen years after its publication. By then, Skinner had become a renowned scientist who was taken seriously in the academic world. His claim that human behavior can be studied scientifically and altered at will, which he had already expounded in 1945 in Walden Two, began to have considerable influence on many areas of thought in the 1960s and 1970s. His ideas not only became the foundation of a school of psychology but also had an immense impact on social reform in the United States and other western countries: if everything humans do, think, and feel is learned by responding to events in the outer environment, the possibilities for societal influence on individuals are endless. The treatment of juvenile delinquency, mental illness, and learning disabilities, the instruction children received in the public school systemall were affected by the apparent effectiveness of employing the techniques of behavior modification.

Yet Skinners ideas were far from universally applauded. Although the soundness of his scientific work was seldom questioned, his far-reaching conclusions about human nature were repudiated by numerous influential critics. Noam Chomsky, Carl Rogers, Joseph Wood Krutch, and Arthur Koestler have repeatedly argued that Skinners behavioral engineering reduces humans to laboratory rats and controlled robots, stripping them of dignity and free will. Skinners refusal to pay attention to anything but observable behavior was thought to threaten a concept at the very root of western civilization: the individual endowed with inalienable rights and personal responsibility. His conclusion that societal survival could be ensured only by making conscious use of the techniques of controlling behavior to induce people to behave for the good of the group was rejected as totalitarian, as was his assertion that scientists could objectively arrive at values that ought to be adopted by society. As a result of the ongoing debate about Skinners controversial ideas, which peaked in 1971 with his publication of Beyond Freedom and Dignity, interest in his early utopian novelhis only work of fictionrose steadily. Quite suddenly, Walden Two was taken seriously.

Skinner gained fame during a time of social unrest in the United States. In the late sixties and early seventies, thousands of young people refused to follow the beaten path and set out to form intentional communities. With the heyday of behaviorism and communal living coinciding, it is perhaps not astonishing that Walden Two inspired some readers to try out Skinners concept of the good life. In the 1960s and 1970s, while Skinners controversial ideas were being widely debated, roughly three dozen intentional communities located almost exclusively in the United States proclaimed themselves to be Walden Two communities, or at least strongly influenced by

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.