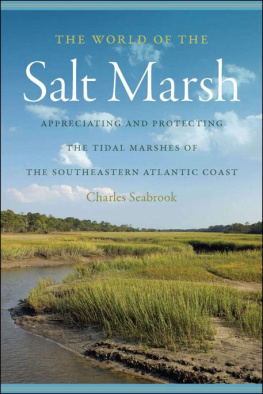

THE WORLD OF THE SALT MARSH

THE WORLD OF THE SALT MARSH

Appreciating and Protecting the Tidal Marshes of the Southeastern Atlantic Coast

CHARLES SEABROOK

2012 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602 www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Designed by April Leidig

Set in Arno Pro by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia

Manufactured by Sheridan Books

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America

12 13 14 15 16 C 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Seabrook, Charles.

The world of the salt marsh : appreciating and protecting the tidal marshes

of the southeastern Atlantic coast / Charles Seabrook.

p. cm. (A Wormsloe foundation nature book)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-2706-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8203-2706-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Salt marshesAtlantic Coast (U.S.) 2. Salt marshesSouthern States.

3. Salt marsh conservationAtlantic Coast (U.S.) 4. Salt marsh conservation

Southern States. 5. Salt marsh ecologyAtlantic Coast (U.S.)

6. Salt marsh ecologySouthern States. 7. Salt marsh restorationAtlantic Coast (U.S.)

8. Salt marsh restorationSouthern States. I. Title.

QH76.5.A85S43 2012

577.60975dc23

2011038256

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8203-4384-6

To my brothers, Jim, Carl, and Wilson

In respectful memory of

Eugene Odum

Edgar Sonny Timmons Sr.

Peter Verity

Richard Wiegert

Sam Hamilton

Ogden Doremus

Charles Wharton

Vernon Jim Henry

Jimmy Chandler

Nick Williams

Reid Harris

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EVERY PERSON WHOSE NAME appears on these pages deserves my considerable thanks for their guidance and kind advice during the research for this book. To name everyone who graciously helped me, though, would require the equivalent of another chapter. I am grateful to them all. I must, however, express my special gratitude to some very helpful individuals: Ron Kneib, Merryl Alber, and Lawrence Pomeroy at the University of Georgia; Fred Holland at the Hollings Marine Laboratory in Charleston; Charlie Phillips, fishmonger and airboat pilot supreme; library director John Cruickshank and public information director Mike Sullivan at the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography; James Holland of the Altamaha Riverkeeper; Larry and Tina Toomer, co-owners of the Bluffton Oyster Company; and my fellow board members of the Center for a Sustainable CoastDave Kyler, Charlie Belin, Steve Willis, Peter Krull, Mindy Egan, Les Davenport, and Ellen Schoolar.

Many thanks to Christa Frangiamore, Judy Purdy, and Laura Sutton, who as editors at the University of Georgia Press encouraged me to pursue the book when it seemed a daunting task. Thanks to Mindy Conner for her skilled editing. And thanks to the entire UGA Press staff for their talent and professional ability.

Finally, thanks to my wife, Laura. Without her, I would be an aimless wanderer.

THE WORLD OF THE SALT MARSH

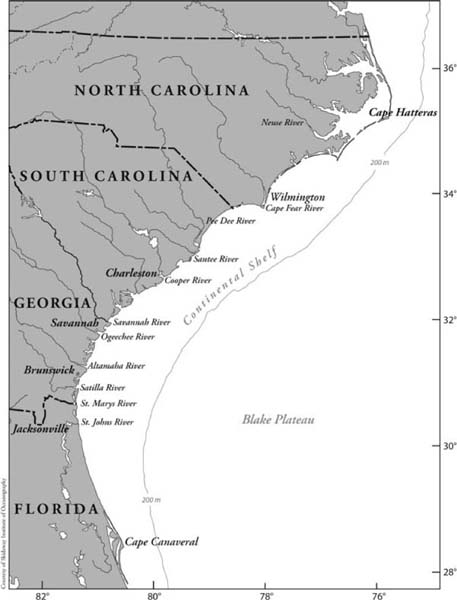

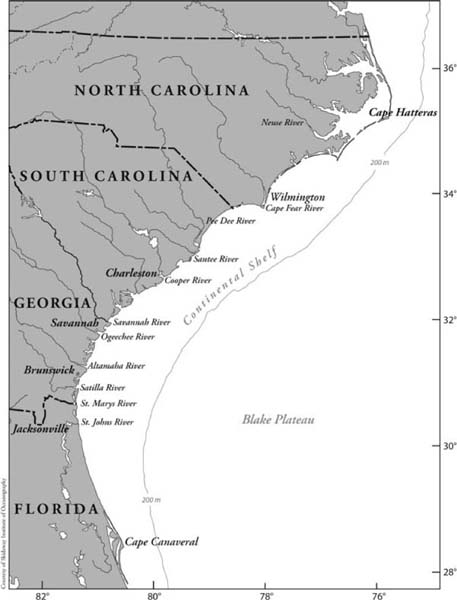

The South Atlantic Bight is an indentation in the coastline stretching roughly from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to Cape Canaveral, Florida, and encompassing the continental shelf offshore.

Map by Anna Boyette at the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography.

INTRODUCTION

I SPENT HALF MY childhood trying to get off an island. I have spent half my adulthood trying to get back.

The island is Johns Island, one of the sleepy, semitropical sea islands nuzzling the South Carolina coast that are surrounded by vast salt marshes, broad sounds, and winding tidal rivers. It was home to my ancestors for two hundred years, a haven where everyone knew my name. My daddy once warned me how it would be when I left: When you leave this island, nobody will give a damn whether your name is Seabrook, he said.

But I could not wait to leave. There were soaring mountains with snowcapped peaks and tropical rainforests with wild, howling monkeys to see. I wanted to ride a camel across the Sahara and descend into deep caverns to gaze upon stupendous geological wonders. I wanted to see Paris, London, New York, Rio, Rome, Istanbul, and the thousands of other places I read about in National Geographic.

So, three days after graduating from high school in 1962, I left my island. Since then I have seen many of those places. As a science reporter for thirty-three years with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution I wrote stories from such far-flung places as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska and the rainforests of Guatemala. I walked on the Great Wall of China, paddled a dugout canoe down an Amazon tributary in Brazil, and rode through the Panama Canal in an outboard skiff. I saw Paris, Rome, London, Rio, Berlin, Beijing, Hong Kong, Prague, Budapest, and other marvels.

But I know now that the most wondrous, magical place of all was the place I left as soon as I got the chancemy island. I remember the moment when I finally realized that. I had been living for many years in Atlanta, and I was crossing the bridge to the island on a glorious autumn afternoon to see my mother. It was high tide, and the golden marsh with the tidal creeks twisting through it glowed softly in the afternoon sun. The beauty took my breath away.

An unnamed salt marsh creek in late summer on Johns Island, South Carolina.

The creeks, of course, have always wound through the marsh; the sun has always set over it. I just hadnt appreciated the splendor of the view before. I was too busy plotting to get away. Now, after years of being away, I long for what I once took for granted.

In my boyhood, Johns Islanda twenty-minute drive from downtown Charlestonwas a place of magnificent spreading live oaks dripping with Spanish moss that formed cathedral-like canopies over the sandy roads and pathways; of stately palmettos that rustled when nudged by the soft air; of the broad Stono River, now placid blue, now roiling green in mood with the sky. Dolphins frolicked in the water and rolled up on mud banks and then back into the water again. You could spend all day sailing the river or searching its high bluffs for arrowheads, rusting Civil War cannonballs, and long-lost pirate booty.

Anyone who flung a cast net into the tidal creeks pulled out bountiful shrimp, blue crabs, and mullet. Oysters crowded the creek banks and were there for the taking. At oyster roasts, we tossed the mollusks onto a redhot sheet of tin, threw wet croaker sacks soaked in salt water over them, let them steam several minutes, then shucked them open to get at the succulent meat.

On certain Sunday afternoons in summer, church members gathered at the rivers edge to witness as the preacher in hip boots dipped the white-robed baptismal candidates into the ebb tide, the best tide for washing away sins.

Next page