B Y V ERNOR V INGE

Tatja Grimms World

The Witling

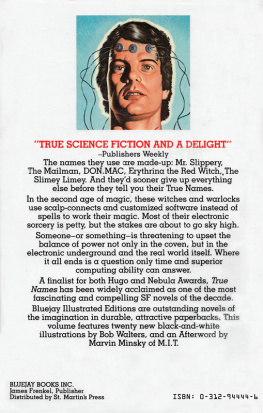

True Names and Other Dangers (collection)

Threats and Other Promises (collection)

Across Realtime

comprising:

The Peace War

The Ungoverned

Marooned in Realtime

*A Fire upon the Deep

*A Deepness in the Sky

*The Collected Stories of Vernor Vinge

*True Names and the Opening of the Cyberspace Frontier (forthcoming)

*denotes a Tor book

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in these stories are either fictitious or are used fictitiously.

THE COLLECTED STORIES OF VERNOR VINGE

Copyright 2001 by Vernor Vinge

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Edited by James Frenkel.

Book design by Jane Regina

An Orb Edition

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

www.tor.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vinge, Vernor.

[Short stories, selections]

The collected stories of Vernor Vinge / Vernor Vinge.

p. cm

ISBN 0-312-87373-5 (hc)

ISBN 0-312-87584-3 (pbk)

1. Science fiction, American. I. Title.

PS3572.I534 A6 2001 2001053966

813'.54dc21

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

Copyright Acknowledgments

Bookworm, Run! Copyright 1966 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Analog Science Fiction Science Fact.

The Accomplice Copyright 1967 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation. First published in Worlds of If Science Fiction.

The Peddlers Apprentice Copyright 1975 by Joan D. Vinge and Vernor Vinge. First published in Analog Science Fiction Science Fact.

The Ungoverned Copyright 1985 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Far Frontiers, Baen Books.

Long Shot Copyright 1972 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Analog Science Fiction Science Fact.

Apartness Copyright 1965 by New Worlds SF.

Conquest by Default Copyright 1968 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Analog Science Fiction Science Fact.

The Whirligig of Time Copyright 1974 by Random House, Inc. First published in Stellar One, Ballantine Books.

Bomb Scare Copyright 1970 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Analog Science Fiction Science Fact.

The Science Fair Copyright 1971 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Orbit 9, G. P. Putnams Sons.

Gemstone Copyright 1983 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Analog Science Fiction Science Fact.

Just Peace Copyright 1971 by Vernor Vinge and William Rupp. First published in Analog Science Fiction Science Fact.

Original Sin Copyright 1972 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Analog Science Fiction Science Fact.

The Blabber Copyright 1988 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Threats and Other Promises, Baen Books.

Win a Nobel Prize! Copyright 2000 by Nature Publishing Group. This article was first published in Nature.

The Barbarian Princess Copyright 1986 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact.

Fast Times at Fairmont High Copyright 2001 by Vernor Vinge.

The Cookie Monster Copyright 2003 by Vernor Vinge. First published in Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact.

Vernor Vinges commentary on a number of stories which appeared in the Baen Books collections True Names and Other Dangers and Threats and Other Promises appeared in substantially similar form in those collections.

Vernor Vinges commentary for The Accomplice appeared in substantially similar form in the program book of the 64 th Anniversary Philadelphia Science Fiction Conference (Philcon 2000).

To all my editors

(including those who have rejected my stories)

for their help over the years

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my editor for this book, Jim Frenkel. More people than I can name have helped me with these stories, but in particular I want to thank those who helped with the new story in this collection, Fast Times at Fairmont High: Sara Baase-Mayers, David Baxter, John Carroll, Bob Fleming, Jim Frenkel, Peter Flynn, Mike Gannis, Pat Hillmeyer, Cherie Kushner, Keith Mayers, Phil Pournelle, Bill Rupp, Mary Q. Smith, and Joan D. Vinge.

Contents

BONUS

T he year 1965 is special for me: thats when I made my first science-fiction sale. In the next few years I sold a number of stories. My ideal length was around twelve thousand words. Shorter than that wasnt enough space to make the point of the story, and with longer stories, I had trouble coordinating characters and detail. Eventually, I became comfortable with novel-length stories. Most of my short fiction has been anthologized, stories scattered through many books: orphans moving from home to home. Publishers are reluctant to do one-author collectionswith happy exceptions, such as the Baen collections in the 1980s and now this Tor collection in 2001.

The Collected Stories of Vernor Vinge contains almost all my published short fiction to date. For the record, the omissions are:

- True Names, which is included in True Names and the Opening of the Cyberspace Frontier ;

- Grimms Story, which is the core of my novel, Tatja Grimms World.

Finally, this Tor collection contains a first appearance, the novella Fast Times at Fairmont High (hot off the word processor).

V ERNOR V INGE

August 2001

I was a child in the 1950s, a little boy who could talk and write better than he could think, but who had a good imagination, and read everything he could by people much smarter than he. I wanted to know the future of science, to participate in revolutions to come. Science fiction seemed a window on all this, I wanted interstellar empires (interplanetary ones at the least). I wanted supercomputers and artificial intelligence and effective immortality. All seemed possible. In fact, our technological success is ultimately based on intelligence. If we could use technology to increase (or create) intelligence The first story I ever wrote (that sold) was a look at this idea. Instead of Artificial Intelligence (Al), I used Intelligence Amplification (IA). The means seemed at hand: After all (I thought) what is memory but retrieval of information? Why couldnt human reason be augmented by hardware? (Perhaps its fortunate that at the time I had no technical knowledge of computers. I might have become discouraged, ended up writing really hardcore science-fiction about punch cards and batch processing.) It was 1962, I was a senior in high school, and I wanted to write about the first man to have a direct mind-to-computer link. I even thought I might be the first person ever to write of such a thing. (In that, of course, I was wrongbut the theme was rare compared to nowadays.) I worked very hard on the story, applying everything I knew about SF writing. I put together a social background that I thought would make things interesting even where the story sagged: cheap fusion/electricity converters had been invented (that worked at room-temperature!), trashing the big power utilities and causing a short-term depression. (In a sense, this was a sequel to Randall Garretts story, Damned If You Dont. I admired that story very much; economic depressions were faraway, alien beasts to me.) And of course, there would be experiments with chimpanzees before the IQ amplifier was tried on my human hero. Having thought things out, I described the plot to my little sister (a tenth-grader). She suffered through my endless recounting, then remarked, Except for the part about the chimpanzee, it sounds pretty dull. What a comedown. Still she had a point. The chimpanzee story had an obvious ending. After it made me famous, I could write the important story, the one with a human hero. John W. Campbell liked the chimpanzee part, too. (And unlike my sister, he got a kick out of the Randall Garrett references.) Eventually, he bought the story for Analog. So. Its 1984 (as seen by a teenager from the early 1960s), and we have a hero with a very serious problem:

Next page