Copyright 2012 by Jack Hitt

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

eISBN: 978-0-307-95518-0

Illustrations by John Burgoyne

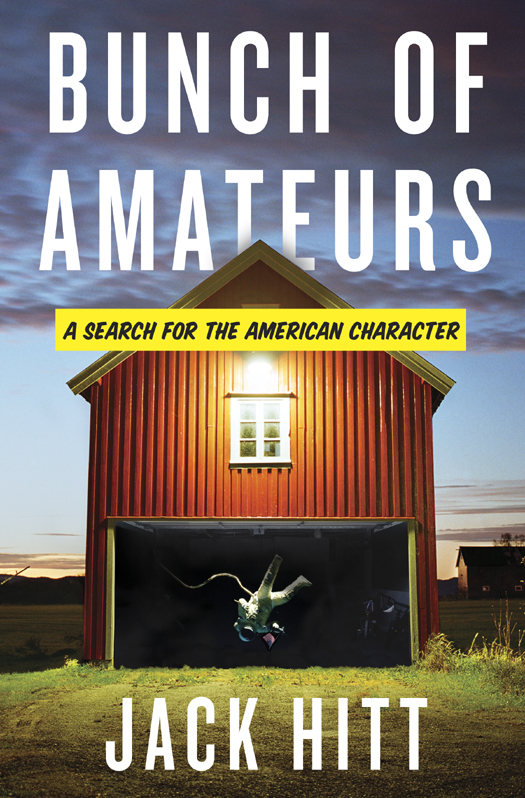

Jacket design by Christopher Brand

Jacket photographs: (Astronaut) Francesco Reginato/Getty Images; (barn) Samuel Hicks/Gallery Stock

v3.1

For Yancey and Tarpley

Contents

1

GUNGYWAMPING

n a forested bottomland of southeastern Connecticut, amid stony outcroppings and strewn granite boulders, lies an unusual cluster of nine beehive-like stone shelters. As far back as anybody can remember, including the Pequot Indians, the area has had a funny name: Gungywamp. When I first heard about the place, I called around and found David Barron, then the president of the Gungywamp Society. He invited me to join him on a walk in the woods with some fresh recruits, mostly married couples in their fifties. He told me that Gungywampers believed the odd stone huts are Celtic dwellings, an abandoned camp left by Irish monks who visited America fifteen hundred years ago.

n a forested bottomland of southeastern Connecticut, amid stony outcroppings and strewn granite boulders, lies an unusual cluster of nine beehive-like stone shelters. As far back as anybody can remember, including the Pequot Indians, the area has had a funny name: Gungywamp. When I first heard about the place, I called around and found David Barron, then the president of the Gungywamp Society. He invited me to join him on a walk in the woods with some fresh recruits, mostly married couples in their fifties. He told me that Gungywampers believed the odd stone huts are Celtic dwellings, an abandoned camp left by Irish monks who visited America fifteen hundred years ago.

After parking our cars on the side of a remote road, a dozen of us slipped into the woods. Barron, a tall man with sprouts of white hair exploding out from under a Greek fishermans cap, marched with vigor, bubbling with enthusiasm. As a guide, he cut a familiar figure. He possessed a partiality for crippling puns. When someone had to peel off early from the group, he shouted to them, Shalom on the range! He smoked so much his white mustache was tainted yellow. He had a salty way of sprinkling his comments with innuendo that amused the wives, yet affected a Victorian coyness about cursing. When I found some trashbeer cans and cigarette buttsobviously left at one shelter by some teenagers, he let fly the foulest term possible: Sheitzen!

Then Barron led us to a large rock. He wanted to know if we noticed anything. There were some lichens on it, not much else; we stared intently. Barron explained that the rock had faded carvings on it and that one of them was a Chi-Rho, a symbol that superimposes the letter X over the stem of a capital P and served as an early emblem of Christianity. We all squinted.

This particular style of Chi-Rho was common among Irish monks during the fifth to seventh centuries A.D. , Barron told us excitedly, linking the symbol to a time when a certain Brendan the Navigator of Ireland, according to legend, sailed west in search of the Promised Land of Saints. Do you see it? We all leaned over, carefully scanning every blotchy divot. An uneasy silence, broken only by the cracking of twigs beneath our boots, seized the forest.

Slightly annoyed at our befuddled postures, Barron turned an exasperated, upturned palm toward some mild indentations. He sneeringly referenced skeptics at Harvard and Yale who had looked at this evidence and were unimpressed. Haaaavard, he said with thick snark. Right away you got the sense that there were two kinds of esoteric knowledge at odds here. The elite evidence-based world of Yaaaaa-uuuull and this other kind of knowledgeBarronic knowledgethat meant you had to see things differently. Barron took a piece of chalk from his pocket and traced over some worn dimples and there it was. A white Chi-Rho leapt off the speckled gray of the boulder like a 3-D trick. Many in the crowd oood and aaahd. It was an emotional moment to stand in this quiet hardwood bottomland and suddenly feel it instantly transform into a place of antiquity. A new idea had us in its grip, this notion that Irish mariners once stood right here fifteen hundred years ago. Then again, a few of us eyeballed another nearby chiseling, smoothed down by weather in much the same way, and we wondered what runic name it went by: JC III.

When you come across a guy like David Barron, you think, Havent I met him before? The eccentric demeanor, the cocksure certainty for his ideas, that panting cascade of arcane information about things like Chi-Rhos. Hes the guy with enough self-accumulated knowledge about local archaeology and medieval orthography and lithic architecture to cobble together a theory about this place. Hes a type, right? Individuals like Barron can be men or women, old or young, but chances are their gusto for their singular obsession is captivating (or irritating, depending on your mood that day). And one other thingIm speaking from personal experience nowpart of this package typically involves an unusual hat.

We all know these people. They are recurring American characters. These people are amateurs.

I say American characters not because the rest of the world doesnt have amateurs. Of course, every place has them and they are everywhere. At its most fundamental, an amateur is simply someone operating outside professional assumptions. The word derives ultimately from the Latin but comes into English via the French word amateur, meaning lover and, specifically, passionate love. Or obsessive love. This powerful emotion usually indicates someones embrace of a notion (invention, theory, way of life) as a compulsive passion for the thingnot the money, fame, or career that could come of it. But there are differences.

In Europe and on other continents, the word hints at class warfare. Credentialism in the Old World suggests the elevation of those occupying a certain station. Amateurs may be taken seriously but, almost by the power of the word, are kept in their place: isolated outside some preexisting professional class, some long-standing nobility.

In America, amateurs dont stay in their place or keep to themselves. So once the word crossed the Atlantic Oceanwhether by St. Brendan or a more traditional wayit came to mean all kinds of, often, conflicting things. Amateur can signify someone who is nearly a professional or completely a fool. The word also encompasses a sense of being pretentious (mere amateur) or incompetent (the meaning one first hears in this books title). In fact, look it up in Rogets Thesaurus and its a wasp nest of contradictionsfalling under five rubrics of meaning: dabbler, dilettante, bungler, virtuoso, and greenhorn. In America, were a little touchy about this word, and for good reason.

Historically, our amateur ancestors grew out of the Ben Franklin tradition of tinkering at home. In the mid-nineteenth century, the homebrew style had to contend with a societal drive to professionalize, a movement that accelerated with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution. That was an era when, for example, the American Medical Association (formed in 1847) sought to distinguish legitimate doctors from snake-oil salesmen, itinerant abortionists, and other makeshift charlatans peddling miracle tonics. Many disciplines organized professional guilds like the AMA or created university departments to grant credentials to the serious practitioners of a craft over the self-schooled.

n a forested bottomland of southeastern Connecticut, amid stony outcroppings and strewn granite boulders, lies an unusual cluster of nine beehive-like stone shelters. As far back as anybody can remember, including the Pequot Indians, the area has had a funny name: Gungywamp. When I first heard about the place, I called around and found David Barron, then the president of the Gungywamp Society. He invited me to join him on a walk in the woods with some fresh recruits, mostly married couples in their fifties. He told me that Gungywampers believed the odd stone huts are Celtic dwellings, an abandoned camp left by Irish monks who visited America fifteen hundred years ago.

n a forested bottomland of southeastern Connecticut, amid stony outcroppings and strewn granite boulders, lies an unusual cluster of nine beehive-like stone shelters. As far back as anybody can remember, including the Pequot Indians, the area has had a funny name: Gungywamp. When I first heard about the place, I called around and found David Barron, then the president of the Gungywamp Society. He invited me to join him on a walk in the woods with some fresh recruits, mostly married couples in their fifties. He told me that Gungywampers believed the odd stone huts are Celtic dwellings, an abandoned camp left by Irish monks who visited America fifteen hundred years ago.