Copyright Hugh Cornwell and Jim Drury 2001

This edition 2010 Hugh Cornwell and Jim Drury

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

ISBN: 978-0-85712-444-9

All Photographs courtesy of the author

The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Visit Omnibus Press on the web: www.omnibuspress.com

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

CONTENTS

In memory of Hans Wrmling

FOREWORD

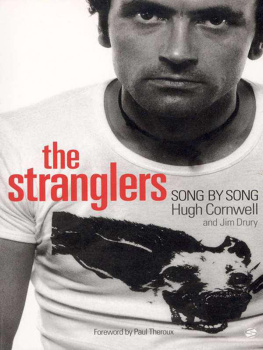

When I first met Hugh Cornwell, whom I admired as lead singer of The Stranglers, I saw an opportunity to talk about music, the punk scene, drugs, sex, groupies and trashed hotel rooms. He wanted to talk about books those that he happened to be reading, others I might recommend. I was surprised by his seriousness, and a bit relieved, too, because he seemed someone I might get to know. Had he been a hellraiser with a riotous past and great mayhem stories, we would have probably enjoyed a lively evening and never seen each other again. As it was, we became friends. Hugh struck me as an intelligent, quietly humorous fellow, with good manners and the sort of appreciative nature that you associate with people who have had a hair-raising close call, if not a brush with death. Such episodes dont make people reckless, in my experience, but rather fill them with a love for life and a kind of quiet gratitude.

This was in the 1980s. Later, Hugh told me that he had known a long period of heroin use and a spell in the slammer. I realise from this book that Pentonville came first, and afterwards the romance with Golden Brown, to use his bewitching expression. I heard that song as I was riding through Dorset one summer evening in 1982, when I was travelling around the British coast, a trip that became the travel narrative The Kingdom By The Sea. In that book, and throughout my 17 years of living in London, I was always on the lookout for songs or films or books that summed up a period. There were so few books and hardly any films, but so much English music was capable of evoking a period. The Specials Ghost Town absolutely captured the demoralised sense of life and the disorder in London in the 1970s. Just as important for me was the music of The Stranglers, and it interests me that in Song By Song Hugh describes how small an impact the early US tours made, The Stranglers following a diminishing interest and blank incomprehension that was parodied by Spinal Tap. Americans couldnt relate to The Stranglers at first, but perhaps that isnt so strange. Look at The Stranglers imagery and the range of reference: the Shah and Khomeini, Victor Hugo, Gregor Mendel, Marie Antoinette and Nostradamus, aliens in New Mexico, the La Brea tar pits and geographical allusions to Japan, Sweden, Morocco and elsewhere, not to mention the sort of suggestions of drugs, violence and mayhem that Hugh discusses here when he relates how The Stranglers have always had an aura of darkness about them. It also seems to me that the last title a US record producer would allow on an album would be Rattus Norvegicus. Anything but that, guys!

When I came to write Dr Slaughter, a novel that I intended to be the embodiment of London in the early 1980s, I devised a plot in which an American girl worked in a think-tank during the day (where she was pawed by her colleagues) and as an escort/hooker at night (where she discussed oil prices with her clients). She was a scholar, a linguist, a cunnilinguist, a fellatrix, a doctoral candidate and a jogger, and her jogging song was Shah Shah A Go Go by The Stranglers. While other people were writing about nailing au pairs, getting Wimbledon tickets, race relations and farting around on the Thames, Dr Slaughter summed up the London I knew. A mention in this novel which was filmed as Half Moon Street pleased Hugh, and the admiration was mutual; I liked his music, and he liked my writing.

Our work even overlapped, and I felt I understood such rebelliousness and the black-clad villains who came out of the woodwork (I never saw them anywhere else) to attend Stranglers concerts. The opacity of British society seemed designed to provoke the young to enrage them, to make them dress perversely and scream obscene lyrics. When Hugh said to the others, I dont want to be a Strangler anymore a lovely way of leaving the group he was also commenting on the times, on his own development, and sort of charting a new course.

George Melly described The Stranglers as the Dada surrealists of the punk movement. Melly knows about art, but I dont agree with that formula. Dadaism was about anti-explanation, anti-meaning, humour and outrage, in equal measure, but Hughs book is proof that every Stranglers lyric had a distinct origin, a reason for being written, a personal meaning in some cases, so deeply personal it would have been unfathomable without his explanation. What a great thing it would be if other musicians and lyricists of stature wrote similar sorts of books, deconstructing (a word Hugh himself might use) their songs, talking about their lyrics and imagery. I am saying this partly because I dont know diddly-squat about music, but I loved living in Britain to the music of The Stranglers, which became a sort of soundtrack to my life in London.

Paul Theroux

September 2001

INTRODUCTION

In 1990, Hugh Cornwell left The Stranglers one of the most extraordinary bands in the history of rock music after 16 eventful years. Throughout this period, The Stranglers were outsiders, ostracised from the outset by their punk brethren, despised by the politically correct and frequently dismissed by a fickle music press. Yet they outlasted and outsold virtually every other band of the era, recording ten hit studio albums and releasing 21 Top 40 singles, an achievement bettered by only a handful of artists.

The four original band members Hugh, Jean-Jacques Burnel, Dave Greenfield and Jet Black were an odd collection of individuals whose career was characterised by spectacular success, dismal failure and suicidal decision-making. They overcame serious drug abuse, near financial ruin, riots, stints in jail and a catalogue of appalling errors and misfortunes to record more than 150 songs and make a lasting impression on a generation of rock listeners.

Over the years, The Stranglers embraced a wide range of musical styles. The bands constant desire to take risks led them to experiment with a diversity of styles, from punk to electropop through to soul and Europop, making The Stranglers impossible to pigeonhole as a musical act.

Numerous column inches have been written about the controversial and unconventional behaviour of The Stranglers, yet little is known about the inspiration for the bands music and the weird and wacky philosophies that influenced their songs. Some Stranglers lyrics contain an aggression that is frightening in intensity and a wit that is savage and unforgiving, but the band have also produced some of the most beautiful, heartfelt songs of the past quarter of a century, Strange Little Girl and Always The Sun to name but two.

![Lambley - And the Band Begins to Play: [Part9 The Definitive Guide to the Beatles White Album]](/uploads/posts/book/213743/thumbs/lambley-and-the-band-begins-to-play-part9-the.jpg)

![Lambley - And the Band Begins to Play: [Part6 The Definitive Guide to the Beatles Rubber Soul]](/uploads/posts/book/213742/thumbs/lambley-and-the-band-begins-to-play-part6-the.jpg)

![Lambley - And the Band Begins to Play: [Part1 The Definitive Guide to the Beatles Please Please Me]](/uploads/posts/book/213741/thumbs/lambley-and-the-band-begins-to-play-part1-the.jpg)