Copyright 2013 Neil Gaiman

The right of Neil Gaiman to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP in 2013

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978 1 4722 0033 4

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

www.headline.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

Table of Contents

About the Author

Neil Gaiman is the author of over thirty acclaimed books and graphic novels. He has received many literary honours.

Born and raised in England, he presently lives in New England and dreams of endless libraries.

Praise for Neil Gaiman:

A very fine and imaginative writer The Sunday Times

Exhilarating and terrifying Independent

Urbane and sophisticated Time Out

A jaw-droppingly good, scary epic positively drenched in metaphors and symbols As Gaiman is to literature, so Antoni Gaudi was to architecture Midweek

Neil Gaiman is a very good writer indeed Daily Telegraph

Exuberantly inventive a postmodernist punk Faerie QueenKirkus Reviews

Excellent [Gaiman creates] an alternate city beneath London that is engaging, detailed and fun to explore Washington Post

Gaiman is, simply put, a treasure-house of story, and we are lucky to have him Stephen King

Neil Gaiman, a writer of rare perception and endless imagination, has long been an English treasure; and is now an American treasure as well William Gibson

Theres no one quite like Neil Gaiman. American Gods is Gaiman at the top of his game, original, engrossing, and endlessly inventive, a picaresque journey across America where the travellers are even stranger than the roadside attractions George R R Martin

Here we have poignancy, terror, nobility, magic, sacrifice, wisdom, mystery, heartbreak, and a hard-earned sense of resolution a real emotional richness and grandeur that emerge from masterful storytelling Peter Straub

American Gods manages to reinvent, and to reassert, the enduring importance of fantastic literature itself in this late age of the world. Dark fun, and nourishing to the soul Michael Chabon

Immensely entertaining combines the anarchy of Douglas Adams with a Wodehousian generosity of spirit Susanna Clarke

Also by Neil Gaiman and available from Headline

American Gods

Stardust

Neverwhere

Smoke and Mirrors

Anansi Boys

Fragile Things

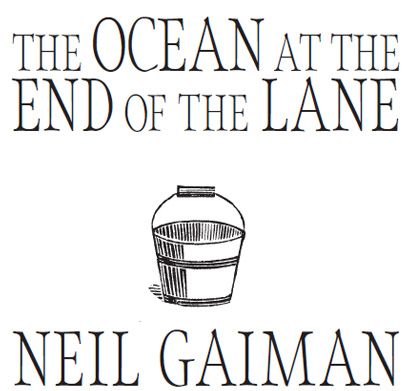

About the Book

It began for our narrator forty years ago when the family lodger stole their car and committed suicide in it, stirring up ancient powers best left undisturbed. Dark creatures from beyond this world are on the loose, and it will take everything our narrator has just to stay alive: there is primal horror here, and menace unleashed within his family and from the forces that have gathered to destroy it.

His only defence is three women, on a farm at the end of the lane. The youngest of them claims that her duckpond is an ocean. The oldest can remember the Big Bang.

The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a fable that reshapes modern fantasy: moving, terrifying and elegiac as pure as a dream, as delicate as a butterflys wing, as dangerous as a knife in the dark from storytelling genius Neil Gaiman.

For Amanda,

who wanted to know

I remember my own childhood vividly I knew terrible things. But I knew I mustnt let adults know I knew. It would scare them.

Maurice Sendak, in conversation with Art Spiegelman, The New Yorker, 27 September 1993

I t was only a duckpond, out at the back of the farm. It wasnt very big.

Lettie Hempstock said it was an ocean, but I knew that was silly. She said theyd come here across the ocean from the old country.

Her mother said that Lettie didnt remember properly, and it was a long time ago, and anyway, the old country had sunk.

Old Mrs Hempstock, Letties grandmother, said they were both wrong, and that the place that had sunk wasnt the really old country. She said she could remember the really old country.

She said the really old country had blown up.

I wore a black suit and a white shirt, a black tie and black shoes, all polished and shiny: clothes that normally would make me feel uncomfortable, as if I were in a stolen uniform, or pretending to be an adult. Today they gave me comfort, of a kind. I was wearing the right clothes for a hard day.

I had done my duty in the morning, spoken the words I was meant to speak, and I meant them as I spoke them, and then, when the service was done, I got in my car and I drove, randomly, without a plan, with an hour or so to kill before I met more people I had not seen for years and shook more hands and drank too many cups of tea from the best china. I drove along winding Sussex country roads I only half remembered, until I found myself headed towards the town centre, so I turned, randomly, down another road, and took a left, and a right. It was only then that I realised where I was going, where I had been going all along, and I grimaced at my own foolishness.

I had been driving towards a house that had not existed for decades.

I thought of turning around, then, as I drove down a wide street that had once been a flint lane beside a barley field, of turning back and leaving the past undisturbed. But I was curious.

The old house, the one I had lived in for seven years, from when I was five until I was twelve, that house had been knocked down and was lost for good. The new house, the one my parents had built at the bottom of the garden, between the azalea bushes and the green circle in the grass we called the fairy ring, that had been sold thirty years ago.

I slowed the car as I saw the new house. It would always be the new house in my head. I pulled up into the driveway, observing the way they had built out on the mid-seventies architecture. I had forgotten that the bricks of the house were chocolate brown. The new people had made my mothers tiny balcony into a two-storey sunroom. I stared at the house, remembering less than I had expected about my teenage years: no good times, no bad times. Id lived in that place, for a while, as a teenager. It didnt seem to be any part of who I was now.

I backed the car out of their driveway.

It was time, I knew, to drive to my sisters bustling, cheerful house, all tidied and stiff for the day. I would talk to people whose existence I had forgotten years before and they would ask me about my marriage (failed a decade ago, a relationship that had slowly frayed until eventually, as they always seem to, it broke) and whether I was seeing anyone (I wasnt; I was not even sure that I could, not yet), and they would ask about my children (all grown up, they have their own lives, they wish they could be here today), and work (doing fine, thank you, I would say, never knowing how to talk about what I do. If I could talk about it, I would not have to do it. I make art, sometimes I make true art, and sometimes it fills the empty places in my life. Some of them. Not all). We would talk about the departed; we would remember the dead.