Wild Beyond Belief. Interviews with Exploitation Filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s (McFarland, 2008)

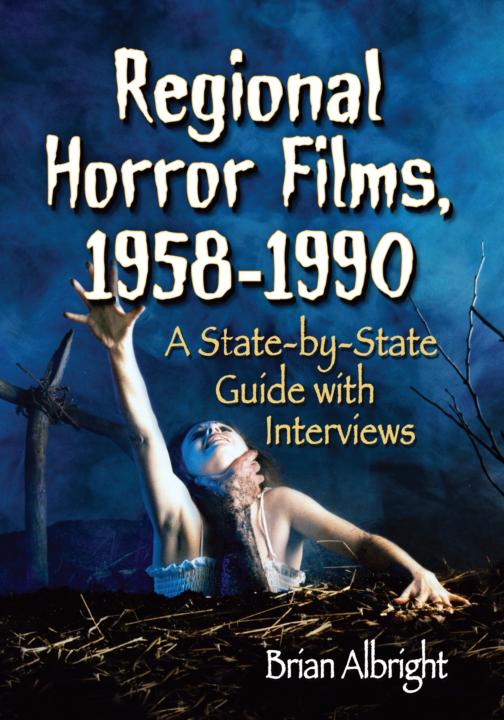

A State-by-State Guide with Interviews

BRIAN ALBRIGHT

First of all, I owe an enormous debt to the people who helped me with my background research, contacts or photos, and who helped me refine the listings and focus the book: Gordon K. Smith in Texas, Ed Tucker in Florida, Fred Olen Ray, Tom Weaver, Bill Warren, Daniel Griffith, George Reis at DVD Drive-In, Rebecca Preston at the Dallas Producers Association, and Joseph Ziemba at Bleeding Skull. And a big thank you to Joel Sanderson at The Basement Sublet of Horror in Kansas for giving me the opportunity to see one of the rarest films in this book, The Beast from the Beginning of Time (1965), and to Johanna Perrino at WCTV in Wadsworth, Ohio, who sent me a copy of the only-slightly-lessrare The Wednesday Children (1973). Jean-Claude Michel and Jose Bogato in Spain deserve special mention for putting me on the trail of Southern Shockers (1985).

Extra special thanks to Chris Poggiali, the world's coolest librarian and curator of The Temple of Schlock, who not only pointed me in the direction of some of the more obscure entries in the book, but who also read through portions of the manuscript and helped correct my boneheaded mistakes. Likewise, the amazing Fred Adelman at Critical Condition granted me access to his mindblowing archive of vintage movie advertisements and video box cover art, and the book would be a much poorer looking pile of paper without his significant contributions.

Thanks to J.R. Bookwalter for publishing my first work and letting me crib the title of his first feature for my blog (to be fair, he stole it from Billy Idol), and to Terry Maher for his opinions, photographic memory and access to his back issues of Fangoria.

And to all my editors: Michael Stein and Jim Wilson at Filmfax, Anthony Timpone, Chris Alexander and Mike Gingold at Fangoria, Steven Puchalski at Shock Cinema, Darryl Mayeski at SCREEM, and Joe Kane at VideoScope.

As always: Adele, my parents, Fritz the Nite Owl, Video Central in Columbus, Star Time Video in Circleville, and B-Ware Video (rest in peace) in Cleveland.

vi

Part I: The Interviews

Part II: The Films

It's the summer of 1964, and you and your family have rolled into the Telegraph DriveIn just outside of Toledo to munch popcorn and watch a seemingly innocuous double feature of Spencer's Mountain (1963) and The Wheeler Dealers (1963).

Suddenly, up on the screen, a sweaty man in a suit appears against a red backdrop and ominously intones: "Ladies and gentlemen, you are about to witness some scenes from the next attraction to play this theater. This picture, truly one of the most unusual ever filmed, contains scenes, which under no circumstances, should be viewed by anyone with a heart condition or anyone who is easily upset. We urgently recommend that if you are such a person, or the parent of a young or impressionable child now in attendance, that you and the child leave the auditorium for the next 90 seconds."

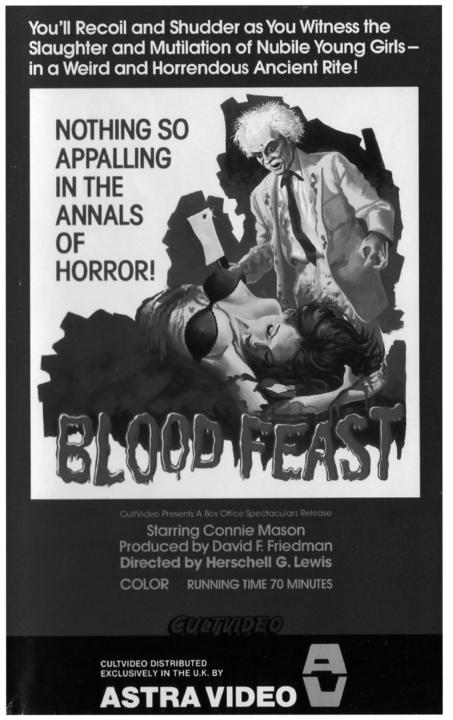

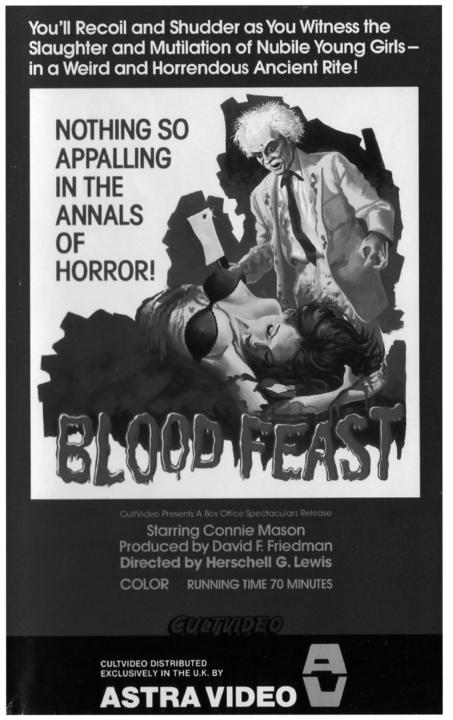

Before you even have time to cover your impressionable child's eyes, let alone consider the logistics of leaving a drive-in for 90 seconds, you are greeted in rapid succession by images of a woman in her bra having her tongue gorily ripped out of her head, two lovers scalped on a beach, a heart plucked from another woman's chest, and a risque bathtub leg amputation, all in dripping color and all featured prominently in the Herschell Gordon Lewis film Blood Feast (1963).

"Nothing so appalling in the annals of horror!" the trailer claimed. And nothing so appalling in the annals of Toledo cinema, apparently, since the local Armstrong Circuit canceled its scheduled screenings of the film after families complained about the unexpectedly grisly trailer.

This was not the first, or last, time Blood Feast (generally credited as the first American gore film) would run into legal problems. When the movie opened in the fall of 1963, drivein audiences responded by lining up for miles to see it, and local bluenoses reacted with shock and horror at its crude gore and crass title. The film was banned in Sarasota after one showing. Newspapers in Pittsburgh refused to even run advertisements for it. A group of East Haven, Connecticut, police officers declared the film objectionable, and a Philadelphia theater owner was arrested for exhibiting an obscene film and contributing to the delinquency of a minor after screening it for an audience of teenagers.

The censors occasionally prevailed against Blood Feast, but the film's producers (Lewis and David F. Friedman) were hardly deterred. They followed Blood Feast with a string of similarly themed gore pictures, and were soon joined by other like-minded filmmakers who were willing to push the limits of good taste for a fast buck.

Blood Feast, in fact, was just the first of what would soon become a flood of horror films that over the course of the next three decades would shock audiences, flummox critics, and completely redefine the boundaries of the genre. In addition to their subversive content, films like Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Last House on the Left (1972), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), I Spit on Your Grave (1978), and Friday the 13th (1980) also shared a very similar production lineage: They were made far outside of Hollywood, produced in burgeoning film communities that had sprouted in Florida, Texas, Oregon, New York and all points in between.

The history of the horror film, at least in the last half of the 20th century, was made as much by enterprising independent filmmakers as it was by the major studios. But the films mentioned above weren't just independent horror films; they were regional horror films, conceived, produced and often distributed entirely in corners of the country not typically associated with the entertainment industry-from the backwoods of Utah to the bayous of Louisiana and the outer boroughs of New York. Made with little regard to genre convention, or in some cases even any basic knowledge of filmmaking, by the 1970s these regional indies were at the vanguard of horror cinema.

Before we go much farther, it might be helpful to provide a better definition of what, exactly, a regional horror film is. Opinions will probably differ, but for my purposes a regional horror film is one that was (a) filmed outside of the general professional and geographic confines of Hollywood; (b) produced independently; and (c) made with a cast and crew made up primarily of residents of the state in which the film was shot.