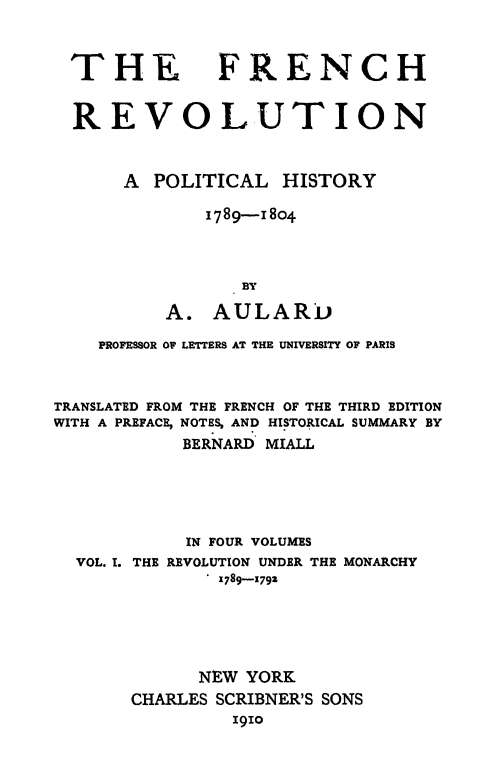

CONTENTS OF THE FIRST VOLUME

PAGE

AUTHOR'S PREFACE ... 9 TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE ..... 19

I. THE MONARCHY. 1789-1792.

CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY ,... -35 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES . 55

CHAPTER I.

DEMOCRATIC AND REPUBLICAN IDEAS BEFORE THE REVOLUTION......79

I. No Republican Party in France. Monarchical opinions of Montescjujeu, Voltaire, d'Argcnson, Diderot, d'Holbach, Helvetius, Rousseau, and Mably, among the illustrious dead: of RayiiaC Condorcet, Mirabeau, Sieyes, d'An

CONTENTS

PAGE

traigues, La Fayette, and CamiUe Desmoulins, among the celebrated and influential living.II. Certain writers aim at the introduction of republican institutions under the Monarchy.III. Increasing weakness of the Monarchy : the opposition of Parliament.IV. Parliament prevents the absolute Monarchy from reforming itself, and opposes the establishment of Provincial Assemblies.V. English and American influence.VI. How far are the writers of the period democratic ?VII. The democratic and republican states of mind.

CHAPTER II.

DEMOCRATIC AND REPUBLICAN IDEAS AT THE OUTSET OF THE REVOLUTION.....127

I. Convocation of the Estates-General. The Ca?iicrs.ll. Formation of the National Assembly.III. The taking of the Bastille and the municipal revolution.IV. The Declaration of Rights.V. Logical consequences of the Declaration.

CHAPTER III.

THE MIDDLE CLASS AND THE PEOPLE (" BOURGEOISIE " AND DEMOCRACY).....161

I. Neither all the logical social consequences nor all the logical political consequences ensue from the Dcctaration of Rights* At this period there arc neither Socialists nor Republicans.II. The organisation of the* Monarchy. III. The organisation of the bourgeoisie as the prtviit-gcc! middle class. The rule of the property-holders.IV. The Democratic movement.V. The application of the rule of the property-holders.VI, The claims of the Democrats arc emphasised.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER IV.

PAGE

FORMATION OF THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND BIRTH OF

THE REPUBLICAN PARTY (1790, 1791). 312

I. The Democratic Party.II. Federation.III. The first Republican Party: Mme. Robert, her paper and her salon. IV. First manifestations of Socialism.V. Feminism.

VI. The campaign against the rule of the bourgeoisie.

VII. Signs of the times ; Republicanism from December, 1790, to June, 1791.VIII. Humanitarian politics.IX. Summary.

CHAPTER V.

THE FLIGHT TO VARENNES AND THE REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT (JUNE SI-JULY 17, 1791) 260

I. The character of Louis XVI. Historic importance of the flight to Varennes.II. The attitude of the Constituent Assembly.III. The attitude of Paris. The people ; the sections; the clubs; the press.IV. The King's return acts as a check on the Republican Party.V. Polemics on the question: "Republic or Monarchy?"VI. The Republican movement in the provinces.VII. The Democrats and the affair of the Champ de Mars.

CHAPTER VI.

THE REPUBLICANS AND THE DEMOCRATS AFTER THE

AFFAIR OF THE CHAMP DE MARS .. 3 I 5

I. Scission and reaction after July i7th.II. Aggravation of the bourgeois system.III. The Assembly closes every legitimate outlet for Democracy and Republicanism. IV. Restoration of the royal power.

CHAPTER VII.

PAGE

FROM THE MEETING OF THE SECOND ASSEMBLY TO JUNE 20, 1792.... , -338

I. Elections to the Legislative Assembly and temporary abdication of the Democratic and Republican parties.II. First acts and policy of the Assembly.III. Public opinion.IV. The King's policy. Declaration of war with Austria. Quarrel between the Assembly and the King.V. Anti-republican politics of Robespierre. VI. The day of June 20, 1792.VII. Its consequences.

AUTHOR'S PREFACE

IN this Political History of the French Revolution, I propose to show how the principles of the Declaration of Rights were, between 1789 and 1804, put into operation by the institutions of the time ; or interpreted by speeches, by the press, by the policies of the various political parties, and by the manifestations of public opinion. Two of these prijiciples, the principle of the equality of rights, and the principle of national sovereignty, were those most often invoked in the elaboration of the new state politic. They are, historically, the essential principles of the Revolution ; variously conceived, differently applied, according to thes period. The chief object of this book is the narration of the vicissitudes which these two principles underwent.

In other words, I wish to write the political history of the Revolution from the point of view of the origin and the development of Democracy and Republicanism.

Democracy is the logical consequence of the principle of equality. Republicanism is the logical consequence of the principle of national sovereignty. These two consequences did not ensue at once. In place of Democracy, the men of 1789 founded a middle-class government, a suffrage of property-owners. In place of the Republic, they organised a limited monarchy. Not until August 10, 1792, did the French form themselves into a Democracy by establishing universal suffrage. Not until September 22nd did they abolish the Monarchy and create the Republic. The republi

can form of government lasted, we may say, until 1804that is, until the time when the government of the Republic was confided to an Emperor. Democracy, however, was suppressed in 1795, by the constitution of the year III, or, if not suppressed, at least profoundly modified by a combination of universal suffrage and suffrage with a property qualification. To begin with the people as a whole was required to surrender its rights in favour of one class the middle class, the bourgeoisie; this bourgeois regime was the period of the Directoire. Then the entire people was required to abdicate its rights in favour of one man, Napoleon. Bonaparte, and this plebiscitary republic was the period of the Consulate. The history of Democracy and the Republic during the Revolution falls naturally under four headings :

1. From 1789 to 1792 the period of the origins

of Democracy and the Republicthat is, of the formation of the Democratic and Republican parties under a constitutional monarchy by a property-owners' suffrage.

2. From 1792 to 1795 was tf 16 period of the

Democratic Republic.

3. From 1795 to 1799 was ^ period of the

Bourgeois Republic.

4. From 1799 to 1809 was the period of the

Plebiscitary Republic.

These transformations of the French state politic manifest themselves in a multitude of facts, in a great complexity of circumstance. " We have lived six centuries in as many years," said Boissy d'Anglas, in 1795. F r > in fact, as it proved impossible to reform the old state of affairs pacifically and slowly, a sudden and violent revolution was inevitable, and the work of destruction, of change, and of reconstruction was done in haste, almost at a blow ; work which must, had matters followed a normal course, according to

precedents, domestic and foreign, have demanded very many years for its consummation. Many as were the facts, short as was the time, the complexity of circumstance entailed a still greater confusion. This complexity arose from the fact that the Revolution, while at work upon domestic organisation, had to sustain a perpetual foreign war ; a war against almost the whole of Europe ; a hazardous war, full of sudden and unforeseen vicissitudes ; and, simultaneously, to cope with intermittent civil war as well. These conditions of war, domestic and foreign, impressed on the development and application of the principles of 1789 a quality of feverish haste ; of makeshift, contradiction, weakness, violence, especially from 1792 onwards. The attempts to constitute the Democratic Republic were made in a military camp ; * under the stress of victory or defeat; in the fear of a sudden invasion, or the enthusiasm of a victory achieved. Men had at the same time to legislate rationally for the future, for times of peace, and empirically for the present, for war. These two motives became confused, in the minds of men and in reality. In the various reconstructions of the political edifice, there was neither unity of plan, nor continuity of method, nor logical sequence.

![Clark - Libraries in the Medieval and Renaissance Periods: The Rede Lecture Delivered June 13, 1894, by J. W. Clark [ 1894 ]](/uploads/posts/book/207578/thumbs/clark-libraries-in-the-medieval-and-renaissance.jpg)

![John Willis Clark - Libraries in the Medieval and Renaissance Periods: The Rede Lecture Delivered June 13, 1894, by J. W. Clark [ 1894 ]](/uploads/posts/book/60919/thumbs/john-willis-clark-libraries-in-the-medieval-and.jpg)