JAKOB VON G UNTEN

A NOVEL BY

ROBERT WALSER

TRANSLATED AND WITH AN INTRODUCTION

BY CHRISTOPHER MIDDLETON

VINTAGE BOOKS

A DIVISION OF RANDOM HOUSE NEW YORK

First Vintage Books Edition, August 1983

Copyright 1969 by Helmut Kossodo Verlag

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American

Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States

by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously

in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Originally published by University of Texas Press in 1969.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Walser, Robert, 1878-1956.

Jakob von Gunten.

Translation of: Jakob von Gunten.

Reprint. Originally published: Austin:

University of Texas Press, 1969.

Bibliography: p.

I. Title.

[PT2647.A64J313 1983] 833'.912 83-5738 ISBN 0-394-72168-3

Manufactured in the United States of America

INTRODUCTION

Jakob von Gunten is one of several narratives of its period which transformed the world of German fiction. It is unlike any other German novel, and unlike any other work of European fiction. First, though, one has to realize that the German novel had for a long time been a compendium of writing in all shapes and sizes. So the journal form of Jakob von Gunten, subtitled "Ein Tage-buch," was not something freakish. At the time when it was written (1908), the crux was a refining of the novel's customary gross form into more compact and elementary forms. Whereas in older novels soliloquy (with introspection) had been one element among others, this element was now becoming independent. More, it was becoming analytic. So one might call Jakob von Gunten an analytic fictional soliloquy. That sounds, true enough, very portentous. In reality, the book is more like a capriccio for harp, flute, trombone, and drums.

Three other fictions of the time show what mode of experience was shaping the transformation of the novel: Musil's Torless (1906), Carl Einstein's Bebuquin (1909), and Rilke's The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (1910). In each book, the hero explores remote and perilous regions of his mind; with perceptions of snailhorn delicacy he maps a shifting "inner world" of feelings and impulses; and he pursues a primal enigmatic reality dwelling somehow between the perilous inner world and the brutish disorder of the external world. Strindberg in Paris had started it with his Inferno (1896). In 1910 Kafka, soon to become master of the absurd, was starting to write his journal, and was already familiar with Walser's prose, which he liked. During these four years, 1906-1910, the point of leverage for a revolution in German fiction was being determined. The spirit, at all events, was crystalizing in the disparate imaginations of these writers: Rilke in Paris; in Berlin unknown to one anotherMusil, Einstein, and Walser; and Kafka in Prague. These cities form a neat right angle across the heart of Europe. Still on the fringe, by Lake Constance, lived another writer who was later to evolve his own form of soliloquy (and who also admired Walser): Hermann Hesse.

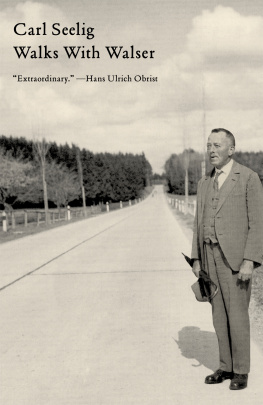

Yet one fails to define Walser by placing him like this among certain crucial "historical developments." Little known as he still is, he was one of the liveliest writers of his time; also he was a sophisticated writer. But his language is peculiar, because it is so unliterary (or what name should be given to this kind of intensity? When a new mode of imagining erupts into literature, it dislocates the rhetoric of its time, and is of subtler stuff than that rhetoric"the infinite arrives barefoot on this earth," says Hans Arp). It would be silly to regard Walser as an intellectual writer in the way that, say, Hofmannsthal, Thomas Mann, or Kafka were intellectual writers. Once, in Berlin, he actually said to Hofmannsthal at a party: "Couldn't you forget for a bit that you're famous?" No, Walser's writing does retain, to the end of his anguished years as a writer, an eccentricity as balanced and as clownishly serious as the paintings of Henri Rousseau. In the framework of the developments sketched above, he stands apart. He is, in significant ways, untutored: something of a "primitive." His prose can display the essential luminous naivete of an artist who creates as if self-reflection were not a barred door but a bridge of light to the real. It is no coincidence that his twenty-five years of writing cover almost exactly the period when "naive" art was being discovered in the West: as a marvel of technique, as a revelation of wonder ranging from the most exotic dreams to the most banal things (while freely swapping their appearances)new and joyous metaphors for a doddering civilization, and energy for Hamlet's heirs. Walser was bom in Biel, Central Switzerland, hi 1878. His father, Adolf, owned a small bookbindery with stationery and toy shop attached. His mother, Elisa Marti, came from a family of country nailsmiths in Schangnau. Not far off in the background was the less lowly paternal grandfather, Johann Ulrich Walser (1798-1866), until 1837 an outspoken liberal-Utopian pastor, who became a journalist and founded his own newspaper, Das Basel-landschajtliche Volksblatt. Adolf and Elisa had eight children: four boys, a girl, two more boys, then another girl. Three of the boys were to distinguish themselves: the second, Hermann (1870-1916) became a professor of geography at Bern University, and Karl (1877-1942) became one of the outstanding stage-designers and book-illustrators of the time (he is the model for the brother described by Jakob von Gunten). Lisa (1874-1944) was also a remarkable person. She ran the household when the mother became mentally deranged, then, with some financial help from an uncle (Friedrich Walser, an architect in Basel), she studied at a seminary in Bern and became a teacher. It was to this strange and beautiful spinster that Walser often looked for guidance during his nomadic life.

He left school when he was fourteen, and worked for a while as a clerk in a bank. Then in 1895 he went to Stuttgart, to work in a publishing house (though he hoped to become an actor). He came to Zurich in the autumn of 1896. In Zurich and several other eastern Swiss towns he earned a living with various odd jobs for the next nine years. His first poems appeared in the Bern newspaper Der Bund in May 1898. Soon after this, he met the elegant litterateur Franz Blei in Zurich, who described him as follows: "A tall, rather gawky lad, with a bony reddish-brown face, over which stood an uncombable shock of fair hair, greyish blue dreamy eyes, and beautifully shaped large hands which came out of a jacket with sleeves too short and didn't know where to go and would have liked best to be stuck into his trouser pockets so as not to be there." During this period, Walser was writing his first prose pieces, in which the clerk (commis) appears as a special kind of underdog. The commis as underdog was a figure who greatly interested the young Kafka in Prague. The period entailed a visit (or two) to Munich (1899? and 1901): the writers associated with the new magazine Die InselOtto Julius Bierbaum, Alfred Walter Heymel, and Rudolf Alexander Schroderwere curious about his work and published poems of his, some prose, and some miniature plays in verse. Walser's first book, Fritz Kochers Auf-sdtze, was published by Insel Verlag in 1904, with illustrations by Karl. It was during the previous year, 1903, that Walser had worked as assistant to an unsuccessful inventor, Karl Dubler-Grassle, at Wadenswil near Zurich: this supplied the setting for his second novel, Der Gehiilfe (1908). His first novel, Geschwister Tanner

Next page