Clairvoyant of the Small

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2021 by Susan Bernofsky.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Bulmer type by IDS Infotech Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020948375

ISBN 978-0-300-22064-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

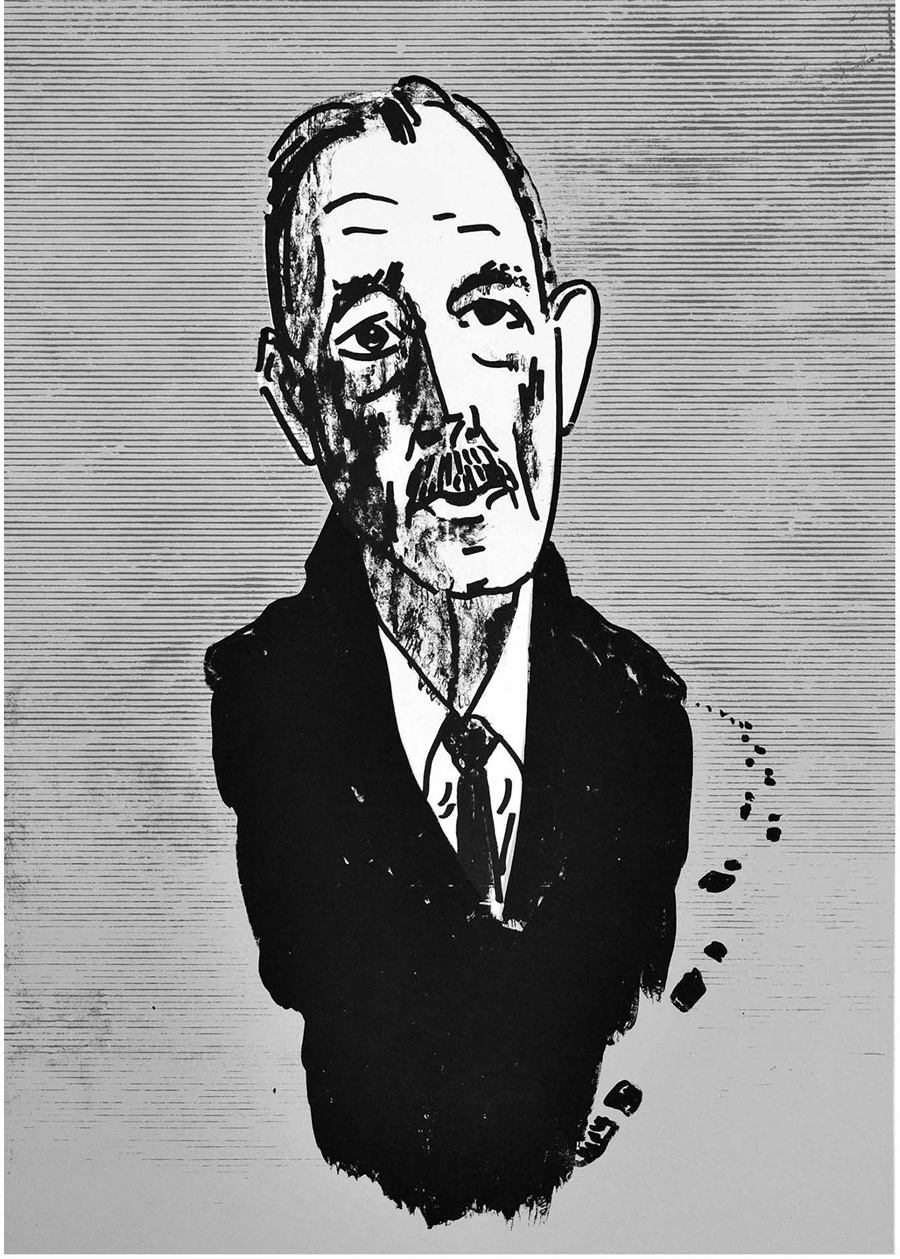

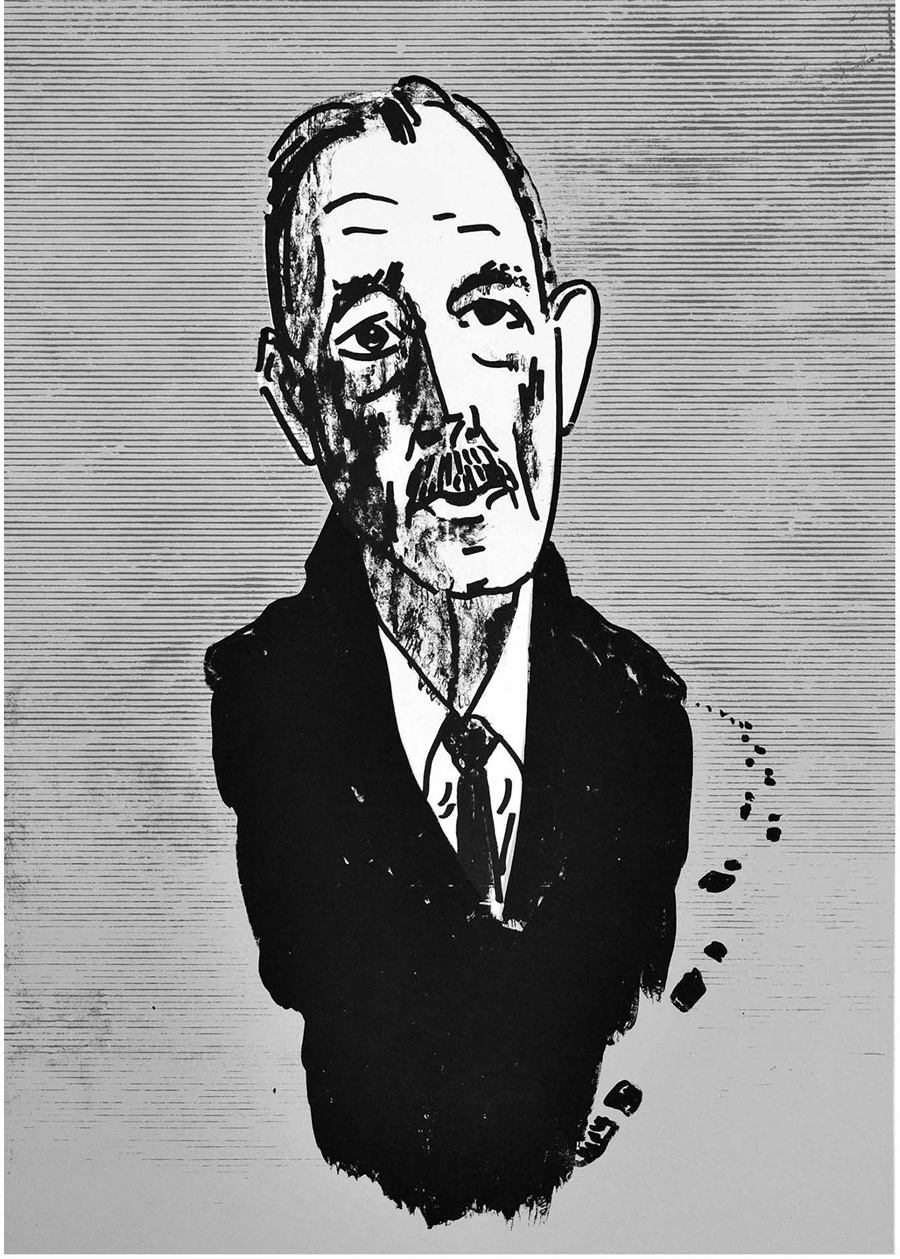

Frontispiece: Klaus Dennhardt, Portrait of Robert Walser

(Private Collection of J. A. Hopkin, Berlin)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Richard

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Searching for Robert Walser

NOT SO LONG AGO, ROBERT WALSER (18781956) was the greatest modernist author youd never heard of. Although much admired as a young writer in his native Switzerland and beyond, including by his contemporaries Franz Kafka, Robert Musil, Hermann Hesse, and Thomas Mann, he was almost forgotten in later lifeand his obscurity outlived him. Only after the centenary of his birth was his work rediscovered and enthusiastically embraced by new generations of readers and scholars. A writers writer celebrated mainly for his brilliant short prose, Walser is now recognized as one of the most singular and original voices of the early twentieth century. He is also revered as a literary antihero who lived and wrote on the margins of society, a romantic outsider.

The bits of Walsers life story best known today are that he trained as a bank clerk and butler when young and later spent decades as an inpatient in a psychiatric clinic, dying while out for a solitary walk in the snow. Readers in the English-speaking world might know his novel about butler school, Jakob von Gunten, on which the film Institute Benjamenta by the Brothers Quay is based, or have picked up a copy of Selected Stories of Robert Walser from 1982 with the foreword by Susan Sontag. Those who encountered Walser more recently may have heard first of the miniature manuscripts (microscripts) he produced during the latter part of his careerthough not only while institutionalized, as is widely and erroneously believed.

Undoubtedly important elements of his story, these together create a somewhat misleading picture of the person and author Robert Walser. In this book, I aim to fill in the gaps and present a portrait of the artist as a literary professional, a master craftsman who encountered many obstacles on his path but remained unwaveringly devoted to his art. For most of his career, Walser eked out a modest living by his pen, above all as an author of the short newspaper texts known as feuilletonsbrief sketches or anecdotes drawn from ordinary life, not unlike The New Yorkers Talk of the Town sectiona genre he transformed into a vehicle for spectacular feats of narration.

The misperception of Walser as a minor writer was to some extent a result of his cultivating this form and devoting his work to small subjects and modest motifs. Spinning tales around insignificance, he preached a gospel of appreciation for the overlooked marvels that surround us, prompting W. G. Sebald to dub him a clairvoyant of the small. We dont need to see anything out of the ordinary, one Walser narrator proclaims, [w]e already see so much. For glorifying the modest and inconspicuous, Walser is cherished by many for whom this stance represents a rejection of and resistance to the pernicious commodification of contemporary life.

Forced to leave school at age fourteen out of economic necessity, Walser apprenticed as a bank clerk in his native Biel while harboring dreams of becoming an actor. After moving to Zurich to work in the bookkeeping division of an insurance firm, he published his first poems and then quit his job to devote himself to writing. Soon after his first book, Fritz Kochers Essays, appeared, he moved to Berlin to join his older brother Karl, an artist and stage-set designer. The two became notorious for their antics and boisterous conduct, a pair of enfants terribles living large among the creative spirits of prelapsarian Berlin, a hotbed of literary and cultural activity. Thanks to his brother, Walser was welcomed into lofty artistic circles. But he felt ill at ease in high society, which he rebelled against by enrolling in butler school, scandalizing his artistic peers. Even after beginning to perform as a writer by producing novelsthree in rapid succession that were well-received by critics, including Musilhis books failed to reach a wider audience; they were too quirky, too seemingly modest, too Swiss. And while his short prose was admired by fellow writers (Kafka loved reading Walser aloud), the young dreamer was soon a has-been with writers block. He retreated back to Switzerland in defeat.

Robert Walsers true career begins here. As his dream of literary stardom fizzled, he began to experiment with short prose forms that, over the next two decades, developed into the high-modernist masterpieces that became his signature achievement. Taking the feuilleton-style essay as his starting point, he layered on strata of descriptive flourish and metaphor until hed constructed elaborate edifices around the simplest topics interwoven with fictional elements, such that it was impossible to tell where essay ended and story began.

Walsers protagonists include children, social outcasts, artists, the impoverished, the marginalized, and the forgotten. All these figures have a penchant for speaking in remarkably erudite, well-crafted, and, above all, lengthy sentences whose complexity and intelligence belie the ostensible insignificance of those who utter them. An astute observer of power differentials, he writes of servants whose employers cower inwardly before them because they understand that their dominance is precarious and must be either voluntarily acknowledged or physically enforced. Thus, the powerful find themselves desiring and depending on their subordinates goodwill. But if nurturing a desire of any sort means surrendering power, Walser describes such renunciation as a joyful, empowering act.

Irony permeates Walsers universe. Not, however, the sardonic and occasionally sarcastic sort famously associated, for example, with Thomas Mann. Walserian irony is a different Weltanschauung altogether. Juxtaposing modesty with stunning verbal opulence, Walsers words ascend from the terrain they purport to map, taking flight and sketching such mesmerizing arabesques that a sentences ostensible meaning becomes the least important thing about it.

Walsers prose pieces spiral around their topics, amassing observations, thoughts, and insights until all human history appears contained in the simple act of, say, looking at a picture. The thick texture of his prose foregrounds the writing itself, his syntactical and semantic complexity reflecting the jangling, anxiety-ridden, euphoric spirit of the modern age. His later narratives are characterized by abrupt changes of topic and direction; a new phrase might be prompted by a rhyme that provokes an association or a metaphor that sparks its own subnarrative. His winding sentences parody bureaucratic German by filling its structures with disorienting phrases. The relativizing adverbs he favorsapproximately, perhaps, probably, so to speakconstrict their object until the firm ground of factual assertion disappears entirely.

Next page