F or as long as she could remember, Francess parents had told her stories about England. But when she got there, the real England wasnt like the stories at all. Frances could see that as soon as the ship pulled into the harbor.

It was only teatime, but night had already fallen. Frances had expected streetlamps and cheery windows with light showing through the curtains. Now all she could see was darkness.

It was something called a Blackout, Francess parents said. It would last all night, every night, until the Great War was over.

Frances and her parents walked down the gangplank and through the dark, cold streets.

They boarded a train, and it rattled through the night. Sometimes it stopped and soldiers got off. More soldiers got on, with their guns and helmets and heavy packs.

When morning came, the train pulled into a small station. The sign on the platform said BINGLEY , and Frances knew that was their stop. Francess father found a man with a horse and cart to take their trunks. He picked up the big leather suitcase that held their clothes.

Frances and her parents walked down Bingleys Main Street, past little shops and a church made of grim, gray stone.

It wasnt at all like the bustling streets of Cape Town, South Africa, where Frances had lived ever since she was a tiny baby. In Cape Town, her father wouldnt have had to lug a big heavy suitcase. They could have taken a taxicab.

Snow lay in drifts along the pavement. Frances picked some up and was surprised to find it was cold. Her parents laughed, but how was she to know? Shed only seen snow on Christmas cards, where it looked as white and soft as cotton.

They walked to the trolley stop and waited in the cold. When the trolley came, it was one of those glorious double-decker ones, so that at least was nice. They rode it through the winter-bare fields until it stopped at a bridge guarded by a big, round tower that looked like a castle. The conductor called out, Cottingley Bar!

Cottingley, Yorkshire, England, was where Frances and her mother would be staying for a while nobody knew how long. They would live with Aunt Polly and Uncle Arthur and Cousin Elsie in their house in Cottingley while Francess father was away in the War. He would be leaving for the battlefields in just two weeks.

A muddy lane led past a woolen mill that stank of grease and raw wool. Frances and her parents followed it up a hill, past a grand manor house, until they came to a village built of stone that seemed even grimmer and grayer than the streets of Bingley. Coal smoke rose from the chimneys into the cold air.

In Cape Town, the air smelled sweet and clear, like fir forests.

In Cape Town, women sold baskets of fragrant flowers that grew wild on the mountains.

Usually when Frances went places, she jumped and skipped and took the bottom four stairs at a bound. Usually she was always being told to hush. But today her parents didnt have to tell her to walk quietly or hush.

They walked up the hill to the very edge of the village, and there stood a row of narrow houses all joined together. In the doorway of the very last one, Aunt Polly waited.

Eeh! she said, smiling widely. She had an odd sort of accent. A Yorkshire accent, Frances realized. She was the most beautiful woman Frances had ever seen.

Her hair was the same color as Francess mothers hair: shining brown with touches of auburn and gold. She wore a beautiful, old-fashioned green dress that went well with her hair.

Frances remembered that first meeting with her aunt for the rest of her life. But oddly enough, she couldnt remember the first time she met her cousin Elsie.

Memory is a funny thing sometimes. Maybe Frances didnt remember because Elsie... well, Elsie was the kind of person who seemed as though youd always known her.

N ow that Frances lived at 31 Main Street, when she came home she opened the front gate and stepped through a tiny garden. It was shaped like a postage stamp, with a low fence all around it. It was the last in a line of postage-stamp gardens, one for each of the seven houses in the row.

The front door opened onto a small, formal parlor with flowered wallpaper. Lace curtains framed the rooms one window, which looked out onto the muddy lane that was Main Street.

If Frances went through the parlor (taking care not to knock over one of the potted palms or bang into the piano), she came to the kitchen, which was even smaller than the parlor.

Stairs from the kitchen led down to the cellar. It was bright, for a cellar, with windows looking out to the back garden. A tin bathtub hung on the wall. The cellar door opened to the back garden, where a path led to the privy.

If Frances bounded back up the stairs, she came to the bedrooms: one for Elsie and one for Elsies parents.

The top story was an attic, which had been made into another bedroom now that Francess family was here.

Still, that made only three bedrooms for two sets of parents and Elsie and Frances. That meant the only place for Frances to sleep was in Elsies room.

Elsies room was so small that there was hardly space for one bed, let alone two. So Frances and Elsie shared a bed.

It was lucky that Elsie didnt mind.

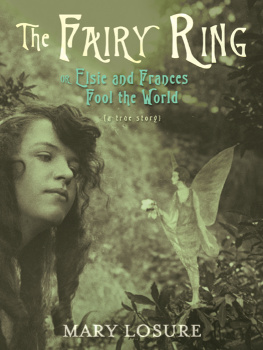

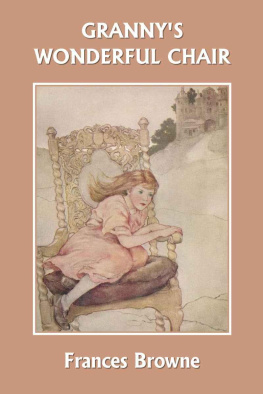

Elsie was much older fifteen going on sixteen, while Frances was only nine. Elsie was a good head taller than Frances, too. Still, she was nice to Frances from the very beginning. Frances was glad, she wrote later, that her first friend in England would be her lighthearted cousin. Elsie had a wide beaming smile and beautiful, thick dark hair. She laughed a lot.

Elsie let Frances look at her watercolor paintings, which she kept in an old chocolate box under her bed. Sometimes she even played dolls with Frances.

Elsies window looked out over the back garden, which sloped down to a little valley, its treetops bare now in the wintertime. A stream ran through it.

Elsie called it a beck, a Yorkshire word for stream. The beck was frozen now, but Elsie said in summer there was a waterfall.

One day, when Frances and her parents had been in Cottingley for two weeks, Francess father packed his things and boarded the train for France. In France, he would be a gunner on the front lines.

Now each week when the newspaper came, it showed rows and rows of photographs of men and boys from Yorkshire who had volunteered to fight, just as Francess father had. Next to each name were a few words saying what had happened to each soldier.

Killed.

Wounded.

Missing.

Sometimes the words were shell shock, septic poisoning, or found in German trench.

And every week, there would be a new batch of photographs.

Francess mothers hair began to thin. The doctor said it was from worry. After a while, Francess mother lost all her hair and wore a wig.

Soldiers in the War didnt get paid very much, so Francess mother had to find a job. She went to work for Uncle Enoch. He had a tailors shop in Bradford, which was a big city bristling with smokestacks from woolen mills.