STORIES IN STONE

By the Same Author

The Seattle Street-Smart Naturalist

A Naturalists Guide to Canyon Country

STORIES

IN

STONE

Travels Through Urban Geology

David B. Williams

Copyright 2009 by David B. Williams

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Walker & Company, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10010.

Published by Walker Publishing Company, Inc., New York

All papers used by Walker & Company are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA.

Williams, David B.

Stories in stone : travels through urban geology / David B.Williams.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-0-802-71981-2

Urban geologyUnited States. Urban geologyItaly. I. Title.

QE39.5.U7W55 2009

550.9173'2dc22

2009005609

To the Rock that will be a Cornerstone of the House from The Collected Poetryof Robinson Jeffers: Volume One, 19201928, edited by Tim Huntby.

Copyright 1938, renewed 1966 by Donnan and Garth Jeffers.

All rights reserved. Used with the permission of Stanford University Press,www.sup.org.

All photographs by David B. Williams except the following: photograph by David B.Williams, used by permission of the Amherst College Museum of Natural History/The Trustees of Amherst College. Photographs by Adam Shyevitch. Photograph courtesy of the Thomas Crane Library, Quincy, Massachusetts, Parker Collection. Photograph by Horace Lyon, used courtesy of Archival Collection, Tor House Foundation. Photograph by John Cipriani, used by permission of National Park Service.

Visit Walker & Companys Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

First U.S. edition 2009

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

To Marjorie

Contents

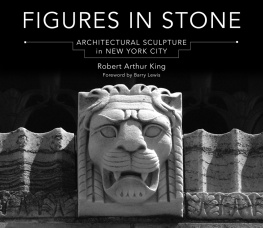

Most people do not think about geology when they are walking on the sidewalks of a major city. But wherever I am in the world, whether strolling through downtown Boston or hiking in the North Cascades, rocks are the first thing I see. I cant walk by a beautiful stone building, or even an ugly one, without touching it and trying to figure out where the stones came from. I go to cemeteries because of the unusual rocks used as grave markers. When I travel I bring back rocks for souvenirs, and I ask friends to pick up rocks from their exotic vacations. When I watch movies, my eyes wander to the buildings in the background to see what stone I can identify.

My passion for rocks began when I majored in geology in college. I had originally planned to go into engineering, but when I took physics and got 16 percent on a quiz I turned to a subject I had excelled at: field trips. I loved being outside learning about the planet and its history. After college, I moved to southern Utah. My passion for stone grew as I hiked, biked, and explored the red rock landscape around Moab, a geologic paradise.

When my wife, Marjorie, decided to pursue her masters degree, we moved to Boston. I hated the first few months. Where I had once traipsed through quiet sandstone canyons, surrounded by thousand-foot-tall cliffs of rock, I now walked through shadowy canyons created by buildings. Where I once hiked on desolate trails, I now crossed busy streets. For the first time in many years I felt disconnected from the natural world.

And then I noticed Bostons buildings. Half-billion-year-old slates abutted 150,000-year-old travertines. Sandstone that formed in Connecticut sat on top of marble that formed in Italy. Metamorphic rocks interfingered with igneous rocks. Fossil-rich, sea-deposited limestones juxtaposed mineral-rich, subduction-created granites. Plus, builders had gone to the effort of cleaning and polishing these fine geologic specimens, making their stories that much easier to read. As I began to notice the stone in buildings, I found the geologic stories that could provide the connection to wildness I had lost.

Now when I need a rock fix, I simply go downtown and wander the business district and look at building stones. I see evidence of continents splitting apart, crashing into each other, and diving deep into the planet; of rivers washing into dinosaur-rich valleys, seas teeming with invertebrates, and hot springs bubbling with bacterial stews; of magma baking limestone into marble, granite carried thousands of miles by plate tectonic movement, and massive trees fossilizing into stunning pieces of petrified wood.

Geology is half the story; building stones also provide the foundation for constructing stories about cultural history. Granite used at the Bunker Hill Monument led to the construction of Americas first railroad. In the brownstones of New York and Boston, the whims of fashion combined with the realities of weathering and erosion to dictate over three hundred years of architectural planning. And in the cottage and tower poet Robinson Jeffers built for his wife and family, you can see how his years of intimate work with stone grounded Jeffers and helped make him one of the most popular American poets of the early twentieth century.

Whether it is a lone iconoclast building his home with rocks he found on a beach or a multinational conglomerate importing millions of tons of marble, we employ building stone to convey sentiments as mundane or grand as we desire them to be. Our use of stone reflects the long relationship between people and natureon levels scientific, emotional, and philosophical. It is a relationship that continues to evolve and to inform our actions.

Stories in Stone offers readers a new window through which to look at urban landscapes. Intriguing cultural and natural history stories are no farther than the nearest building. Building stone did not change the world. Building stone is the world. And it will outlast us all.

THE MOST HIDEOUS STONE

EVER QUARRIEDNEW YORK

BROWNSTONE

In some thirty years every noble cliff will be a pier, and the

whole island will be densely desecrated by buildings of brick,

with portentous facades of brown-stone, or brown-stonn,

as the Gothamites have it. Edgar Allan Poe,

Doings of Gotham, May 14, 1844

Little I ask; my wants are few;

I only wish a hut of stone,

(A very plain brown stone will do,)

That I may call my own;

And close at hand is such a one,

In yonder street that fronts the sun.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Contentment, 1858

I F AMERICA IN the late 1800s was the land where the streets were paved with gold, in Brooklyn and Manhattan the streets were lined with chocolate: chocolate stores, churches, and mansions. But above all, row houses, better known as brownstones. They stretched for block upon block, mile after mile, wearying the eye, as one detractor sneered. In 1880 78 percent of the stone structures in Manhattan had a front of brownstone; in Brooklyn, 96 percent. Brownstones housed the poor, the growing middle class, and the titans of the Gilded Age, such as William Astor II, J. P. Morgan, and Jay Gould.