For Paul LeClerc

You always get it wrong.

Philip Roth to David Plante

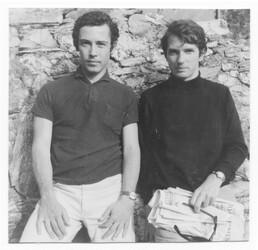

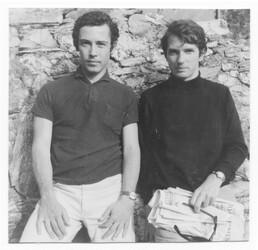

Nikos Stangos and David Plante by Stephen Spender, San Andrea di Rovereto di Chiavari, 1968

Contents

June 1966

As I was approaching from one end of the street the house where Nikos lives, 6 Wyndham Place, I saw him approaching from the other end. He was wearing a dark business suit and carrying a briefcase, returning from the office of the press attach at the Greek Embassy.

Meeting me, he said, If youd come a minute earlier, you would have rung and no one would have answered.

Id have come back, I said.

I followed close behind him as he opened doors with keys into his flat, so close I bumped into him when he paused just inside to turn to me to ask me, his face so near mine I could have leaned just a little forward and kissed him, if Id like to go out or stay in to eat.

Id prefer to stay in, I said.

You like staying in?

I do.

So do I, he said.

He said hed change, and I, in the living room, looked around for something Greek, but saw nothing.

He came from his bedroom wearing grey slacks and a darker grey cardigan, and we had drinks before, he said, hed prepare us something to eat.

He told me how much he likes America, how much he likes Americans, who were, he believed, the only people capable of true originality.

I asked him why he was living in London.

Because, he said, living in London he was not living in Athens. His job in the office of the press attach was the only job he had been able to get that would allow him to leave Greece.

Why?

He would tell me later.

I said, I have a lot to learn about Greece.

He showed me one of his poems, written in English. It was called Pure Reason, and it was a love poem, addressed to you. The poem read almost as if it were arguing a philosophical idea with the person addressed, the terms of the argument as abstract as any philosophical argument. The philosophical idea is reasoning at its purest. What is remarkable about the poem is that, in conveying, as it does, intellectual purity, it conveys, more, emotional purity, and it centres the purity intellectual and emotional and moral in the person with whom the poet is so much in love. I had never read anything like it.

When I handed the poem back to him, he asked me if I would stay the night with him.

In his bed, he said to me, Even if youre worried that it would hurt me, you must always tell me, honestly, what you think, because, later, your dishonesty would hurt much more.

I said, Im not certain what I think.

About me?

About everything.

I am staying with i in his small flat in Swiss Cottage.

He is at work, at Heathrow Airport, where he welcomes and sorts out the problems of visitors using his languages, besides English, Turkish, Greek, Hungarian, Spanish, making him linguistically the most cosmopolitan person I know.

Seven years ago, the i I came to London longing to be with is no longer the i I now know. I was in love with him. I dont love him as I so loved him, but he is a friend.

It seems to me that the i I loved is contained within a room, a moonlit room, in Spain, in a seaside town in Spain, we both in beds across the room from each other, talking. Never mind how we found ourselves in that room, in our separate beds across the room from each other, talking, but remember the smell of suntan lotion, remember the sensation of skin slightly burnt by the sun, remember that skin seemingly made rough by sea salt, remember lying naked in the midst of a tangled sheet, the erection of a nineteen-year-old who had never had sex bouncing against his stomach. We talked, we talked, I cant remember about what perhaps my telling him that my holiday in Spain would soon come to an end and I would go to the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium, for the academic year, emphasizing my regret that I would be leaving Spain, which would be leaving all that was promised in my having met him and then silence between us. He got up from his bed and, naked, went to the open window and leaned out into the moonlight and breathed the fresh pre-dawn air, from where he turned to me and I held out my arms to him. Never, never had I known such a sensation, never, and I fell in love with i for the wonder of that sensation.

A sensation I had to have again and again with him, because I felt that it was only with him that such a sensation was possible.

I went to Louvain, but longed for i in Spain.

When he wrote that he would be in London for the winter holidays, I, possessed by my love, came to London.

He did not love me.

Leave this, from seven years ago, but remember that moonlit room.

When I told i that I had met someone named Nikos Stangos, whom I liked, he said he would find out about this Nikos Stangos through his connections. He smiled his slow, sensual, ironical smile, and said he had many connections, in Turkey, in Greece, in Spain, even in Hungary if I was interested, and, of course, in London.

Later, i told me he had made contact with a Greek who had met Nikos, and, as always with his slow, sensual, ironical smile, as if this was his attitude towards all the world, he said that he had heard that Nikos, working in the Press Office of the Greek Embassy, is acceptable.

I tried to smile, saying, Thats good to know.

I rang Nikos at the Press Office of the Greek Embassy. He said he had thought of going, that evening, to a cello recital by Rostropovich at the Royal Festival Hall. Would I like to go with him? During the recital I was attentive to his attention to the music. As always, I felt that he was in a slight trance; it showed in his stillness, but also in what appeared to me a presence about him, as if his calm extended around his body.

After the recital, he was silent. I didnt know why he was so silent, but I, too, remained silent. Delicate as the calm was that appeared to extend all about him, I felt, within him, a solid gravity; it was as if that gravity caused the outward, trance-like calm by its inward pull. Silent, we crossed the Thames on the walkway over Hungerford Bridge. The trains to the side of the walkway made the bridge sway. In the middle, Nikos reached into a pocket of his jacket and took out a large copper penny, which he threw down into the grey-brown, swiftly moving river far below.

Whats that for? I asked.

For luck, he said.

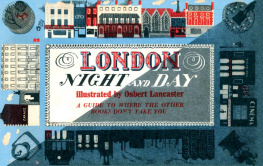

The evening was warm and light. We walked from the Embankment at Charing Cross up to Trafalgar Square, all the while silent.

In Trafalgar Square, he suggested we sit, and we walked among the people standing in groups to the far left corner, behind a great, gushing fountain, where there was no one else and we sat on a stone bench.

We wondered who, in history, had first thought of a water-gushing fountain. In ancient Greece, Nikos said, a fountain was usually a public spigot that water flowed from to fill jugs brought by women. Perhaps the ancient Romans first thought of a gushing fountain that had no use but to look at?

After a silence, Nikos said he had thought very carefully, and he wanted me, too, to think carefully, about what he was going to say. It was very, very important that I be totally honest.

He was in a love relationship with an older Englishman, who was in fact away, and Nikos decided that on the Englishmans return he would tell him their love relationship must come to an end. He had decided this on meeting me, but I must not think that this meant I should feel I had to return the feelings Nikos had for me. I was free, and I must always know that I am free. Then he asked me if I would live with him.

Next page