ARTIFICIAL HELLS

Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship

CLAIRE BISHOP

This edition first published by Verso 2012

Claire Bishop 2012

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-84467-796-2

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bishop, Claire.

Artificial hells : participatory art and the politics of spectatorship / by Claire Bishop. 1st [edition].

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-84467-690-3 ISBN 978-1-84467-796-2 (ebook)

1. Interactive art. I. Title.

N6494.I57B57 2012

709.0407dc23

2012010607

Contents

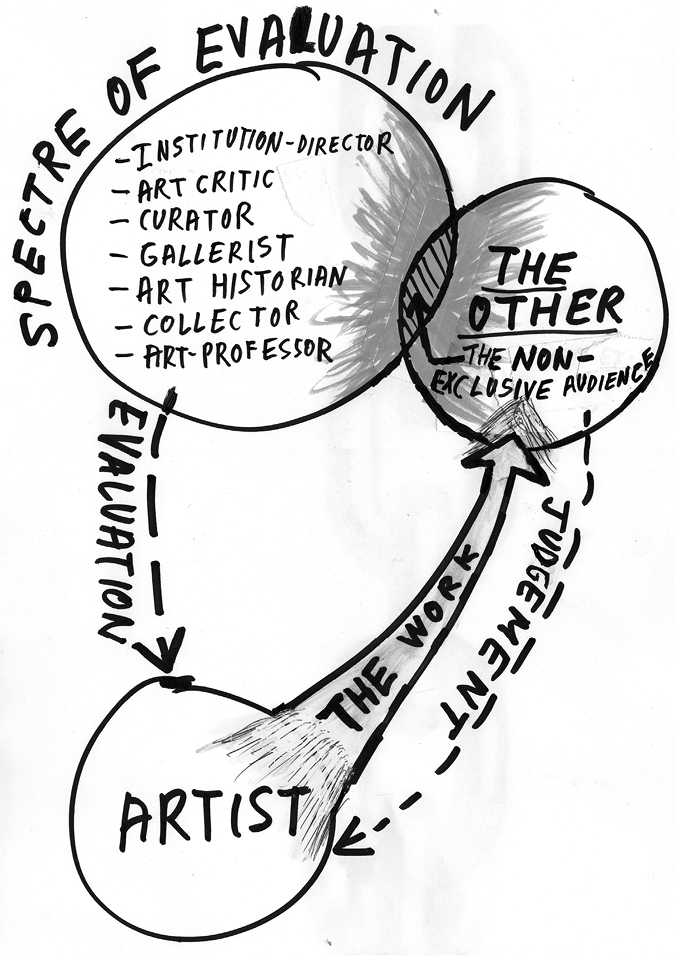

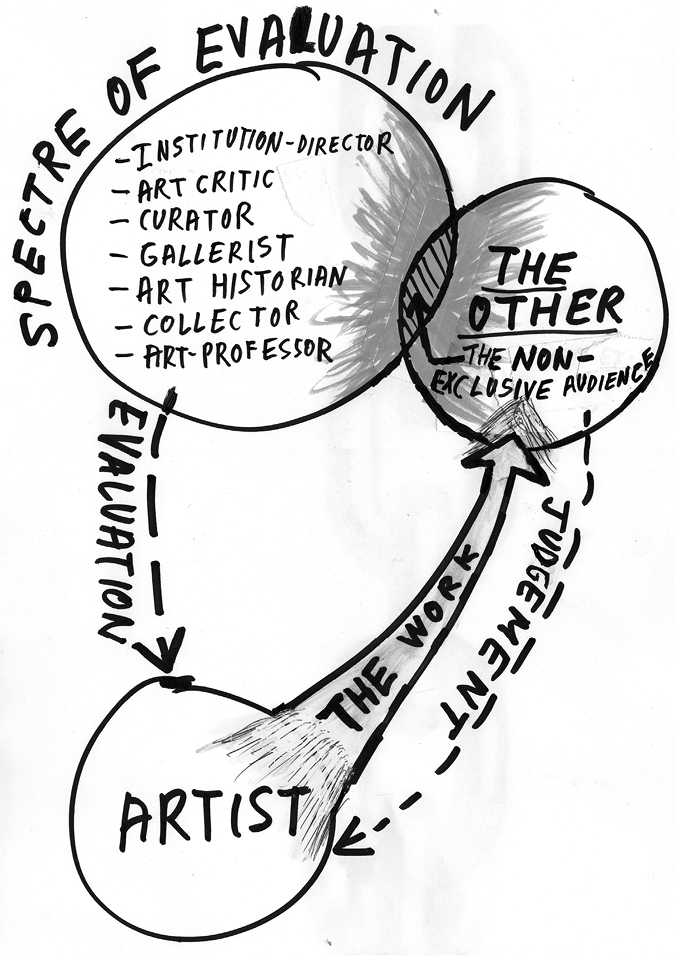

Thomas Hirschhorn, Spectre of Evaluation , 2010, ink on paper

Introduction

All artists are alike. They dream of doing something thats more social, more collaborative, and more real than art.

Dan Graham

Alfredo Jaar hands out disposable cameras to the residents of Catia, Caracas, whose images are shown as the first exhibition in a local museum ( Camera Lucida , 1996); Lucy Orta leads workshops in Johannesburg to teach unemployed people new fashion skills and discuss collective solidarity ( Nexus Architecture , 1997); Superflex start an internet TV station for elderly residents of a Liverpool housing project ( Tenantspin , 1999); Jeanne van Heeswijk turns a condemned shopping mall into a cultural centre for the residents of Vlaardingen, Rotterdam ( De Strip , 20014); the Long March Foundation produces a census of popular papercutting in remote Chinese provinces ( Papercutting Project , 2002); Annika Eriksson invites groups and individuals to communicate their ideas and skills at the Frieze Art Fair ( Do you want an audience? , 2004); Temporary Services creates an improvised sculpture environment and neighbourhood community in an empty lot in Echo Park, Los Angeles ( Construction Site , 2005); Vik Muniz sets up an art school for children from the Rio favelas ( Centro Espacial Vik Muniz , Rio de Janeiro, 2006).

These projects are just a sample of the surge of artistic interest in participation and collaboration that has taken place since the early 1990s, and in a multitude of global locations. This expanded field of post-studio practices currently goes under a variety of names: socially engaged art, community-based art, experimental communities, dialogic art, littoral art, interventionist art, participatory art, collaborative art, contextual art and (most recently) social practice. I will be referring to this tendency as participatory art, since this connotes the involvement of many people (as opposed to the one-to-one relationship of interactivity) and avoids the ambiguities of social engagement, which might refer to a wide range of work, from engag painting to interventionist actions in mass media; indeed, to the extent that art always responds to its environment (even via negativa ), what artist isnt socially engaged? This book is therefore organised around a definition of participation in which people constitute the central artistic medium and material, in the manner of theatre and performance.

It should be stressed from the outset that the projects discussed in this book have little to do with Nicolas Bourriauds Relational Aesthetics (1998/2002), even though the rhetoric around this work appears, on a theoretical level at least, to be somewhat similar.

This orientation towards social context has since grown exponentially, and, as my first paragraph indicates, is now a near global phenomenon reaching across the Americas to South East Asia and Russia, but flourishing most intensively in European countries with a strong tradition of public funding for the arts. Although these practices have had, for the most part, a relatively weak profile in the commercial art world collective projects are more difficult to market than works by individual artists, and less likely to be works than a fragmented array of social events, publications, workshops or performances they nevertheless occupy a prominent place in the public sector: in public commissions, biennials and politically themed exhibitions. Although I will occasionally refer to contemporary examples from non-Western contexts, the core of this study is the rise of this practice in Europe, and its connection to the changing political imaginary of that region (for reasons that I will explain below). But regardless of geographical location, the hallmark of an artistic orientation towards the social in the 1990s has been a shared set of desires to overturn the traditional relationship between the art object, the artist and the audience. To put it simply: the artist is conceived less as an individual producer of discrete objects than as a collaborator and producer of situations ; the work of art as a finite, portable, commodifiable product is reconceived as an ongoing or long-term project with an unclear beginning and end; while the audience, previously conceived as a viewer or beholder, is now repositioned as a co-producer or participant . As the chapters that follow will make clear, these shifts are often more powerful as ideals than as actualised realities, but they all aim to place pressure on conventional modes of artistic production and consumption under capitalism. As such, this discussion is framed within a tradition of Marxist and post-Marxist writing on art as a de-alienating endeavour that should not be subject to the division of labour and professional specialisation.

In an article from 2006 I referred to this art as manifesting a social turn, but one of the central arguments of this book is that this development should be positioned more accurately as a re turn to the social, part of an ongoing history of attempts to rethink art collectively. Each phase has been accompanied by a utopian rethinking of arts relationship to the social and of its political potential manifested in a reconsideration of the ways in which art is produced, consumed and debated.

The structure of the book is loosely divided into three parts. The first forms a theoretical introduction laying out the key terms around which participatory art revolves and the motivations for the present publication in a European context. The second section comprises historical case studies: flashpoints in which issues pertinent to contemporary debates around social engagement in art have been particularly precise in their appearance and focus. The third and final section attempts to historicise the post-1989 period and focuses on two contemporary tendencies in participatory art.

Some of the key themes to emerge throughout these chapters are the tensions between quality and equality, singular and collective authorship, and the ongoing struggle to find artistic equivalents for political positions. Theatre and performance are crucial to many of these case studies, since participatory engagement tends to be expressed most forcefully in the live encounter between embodied actors in particular contexts. It is hoped that these chapters might give momentum to rethinking the history of twentieth-century art through the lens of theatre rather than painting (as in the Greenbergian narrative) or the ready-made (as in Krauss, Bois, Buchloh and Fosters Art Since 1900 , 2005). Further sub-themes include education and therapy: both are process-based experiences that rely on intersubjective exchange, and indeed they converge with theatre and performance at several moments in the chapters that follow.

Next page