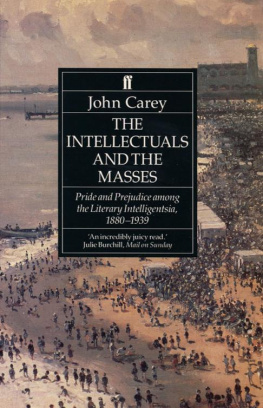

Preface

This book is about the response of the English literary intelligentsia to the new phenomenon of mass culture. It argues that modernist literature and art can be seen as a hostile reaction to the unprecedentedly large reading public created by late nineteenth-century educational reforms. The purpose of modernist writing, it suggests, was to exclude these newly educated (or semi-educated) readers, and so to preserve the intellectuals seclusion from the mass.

The mass is, of course, a fiction. Its function, as a linguistic device, is to eliminate the human status of the majority of people or, at any rate, to deprive them of those distinctive features that make users of the term, in their own esteem, superior. Its usage seems to have been originally neither cultural nor political but religious. St Augustine writes of a massa damnata or massa perditionis (condemned mass; mass of perdition), by which he means the whole human race, with the exception of those elect individuals whom God has inexplicably decided to save. Even in modern times, the belief that God is implicated in the condemnation of the mass lingers on among intellectuals, as I show in Chapter 4. Those not saved will, Augustine trusts, burn in Hell. This well-established Christian precedent for disposing of the surplus mass by combustion was, as my final chapter notes, given practical expression in our century in Hitlers death camps.

My first four chapters are based on the T. S. Eliot Memorial Lectures that I gave at the University of Kent in November 1989. I added the remaining case studies because I wanted to see how the ideas in the lectures would apply to a number of individual writers, each of whom was conscious (though in contrasting ways) of the mass as a new and challenging presence, and none of whom I had had a chance to write on before.

I should like to thank Mrs Valerie Eliot, Matthew Evans, Robert McCrum and the other directors of Faber and Faber for inviting me to give the Eliot Lectures. For my generous welcome at Canterbury, and for enthusiastic feedback and criticism, I am indebted to Shirley Barlow, Master of Eliot College, Bill Bell, Keith Carabine, David Ellis, Krishnan Kumar and Michael Irwin. I greatly enjoyed and benefited from my stay among them.

The first of my two chapters on Wells was given, in shorter form, as the 1990 Henry James Lecture at the Rye Festival. I am grateful to Dr lone Martin and to Anthony Neville, that prince of booksellers, for endowing the lecture and asking me to give it. Dr Martin and her husband kindly entertained me at Lamb House, where I had the unexpected (and, given this books general tenor, rather inappropriate ) honour of sleeping in Henry Jamess bedroom.

To record all the friends and colleagues I have pestered and gained stimulus from would make an embarrassingly long list, but six I cannot omit David Bodanis, David Bradshaw, Martin Green, David Grylls, Peter Kemp and Craig Raine, for whose wisdom and encouragement, much thanks.

John Carey,

Merton College, Oxford,

March 1992

Notes

See Augustines Enchiridion in J. Rivire (ed.), Oeuvres de Saint Augustin, Vol. IX , Exposs Gnraux de la Foi, Descle de Brouwer, Paris, 1947, pp. 152, 3467, and Contra Duas Epistulas Pelagianorum, Book 2, Para. 13, in F. J. Thonnard, E. Bleuzen and A. C. de Veer (eds.), Oeuvres, Vol. XXIII , 1974. See also the use of massa in the Vulgate, Romans 9: 21, from which Augustine derives the term.

PART I

Themes

[1]

The Revolt of the Masses

The classic intellectual account of the advent of mass culture in the early twentieth century was by the Spanish philosopher Jos Ortega y Gasset. His book was called, in its English translation, The Revolt of the Masses , and it was published in 1930. The root of its worries is population explosion. From the time European history began, in the sixth century, up to 1800, Europes population did not, Ortega points out, exceed 180 million. But from 1800 to 1914 it rose from 180 to 460 million. In no more than three generations Europe had produced a gigantic mass of humanity which, launched like a torrent over the historic area, has inundated it.

In Ortegas analysis, population increase has had various consequences. First, overcrowding. Everywhere is full of people trains, hotels, cafs, parks, theatres, doctors consulting rooms, beaches. Secondly, this is not just overcrowding; it is intrusion. The crowd has taken possession of places which were created by civilization for the best people. A third consequence is the dictatorship of the mass. The one factor of utmost importance in the current political life of Europe is the accession of the masses to complete social power. This triumph of hyperdemocracy has created the modern state, which Ortega sees as the gravest danger threatening civilization. The masses believe in the state as a machine for

Ortegas ideas recall those of Nietzsche, who prefigures many of the developments we shall be concerned with. Nietzsche similarly deplores overpopulation. Many too many are born, his Zarathustra declares, and they hang on their branches much too long. I wish a storm would come and shake all this rottenness and worm-eatenness from the tree! Where the rabble drink, all fountains are poisoned. Zarathustra also denounces the state, which overwhelms the individual. It is the coldest of all cold monsters. In it universal slow suicide is called life. It was invented for the sake of the mass the superfluous. Nietzsches message in The Will to Power is that a declaration of war on the masses by higher men is needed. The times are critical. Everywhere the mediocre are combining in order to make themselves master. The conclusion of this tyranny of the least and the dumbest will, he warns, be socialism a hopeless and sour affair which negates life.

We should see Nietzsche, I would suggest, as one of the earliest products of mass culture. That is to say, mass culture generated Nietzsche in opposition to itself, as its antagonist. The immense popularity of his ideas among early twentieth-century intellectuals suggests the panic that the threat of the masses aroused. W. B. Yeats recommended Nietzsche as a counteractive to the spread of democratic vulgarity, and George Bernard Shaw nominated Thus Spake Zarathustra as the first modern book that can be set above the Psalms of David. True, Nietzsches acolytes seem often to have read him selectively, in a bid to harmonize his doctrines with socialism, democracy or even feminism. The influential A. R. Orage, for example, editor of the New Age (which featured some eighty items relating to Nietzsche between 1907 and 1913), published two studies of Nietzsche which give a very partial idea of their subject. However, Orages admiration for the white heat of Nietzsches brain is unstinting, and he reports that Nietzsche is being discussed all over Europe in the most intellectual and aristocratically-minded circles.

Nietzsches view of the mass was shared or prefigured by most of The great Norwegian novelist Knut Hamsun provides an extreme example of this anti-democratic animus. Hamsuns novel Hunger , published in 1890, was a seminal modernist text. Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse and Gide all recorded their debt to Hamsun, and Isaac Bashevis Singer has called him the father of the modern school of literature. Hamsuns Nietzschean view of the mass is epitomized in a speech by his character Ivar Kareno, hero of the Kareno trilogy, a young, struggling author of fiercely anti-democratic views: