THE CHANGING

CONCEPT

OF REALITY IN ART

by

ERWIN ROSENTHAL

Introduction by Deborah Rosenthal

A Biographical Note by Julia Rosenthal

ARCADE PUBLISHING NEW YORK

Copyright 1962 by Erwin Rosenthal; copyright 2012 by Estate of Erwin Rosenthal

Introduction copyright 2012 by Deborah Rosenthal

Biographical Note copyright 2012 by Julia Rosenthal

The publishers are pleased to note the use by permission of the following artists works and appropriate copyrights:

Paul Klee, Realm of Birds copyright 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Wassily Kandinsky, Red"; Matta, The Disasters of Mysticism, 1942; Georges Rouault, Head of Christ, Le Christ au Lac de Tibriade copyright 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Pablo Picasso: Sonnets, Histoire Naturelle, Saint Matorel, Odysseus and the Sirens, Les Metamorphoses, Small Female Figure, Seuno y Mentir de Franco, Seated Female, copyright 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Arshile Gorky, Agony, copyright 2012 The Arshile Gorky Foundation/The Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or arcade@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Arcade Publishing and Artists & Art are trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

www.arcadepub.com

10 987654321

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-769-8

Printed in China

TO KARL KUP

Acknowledgments

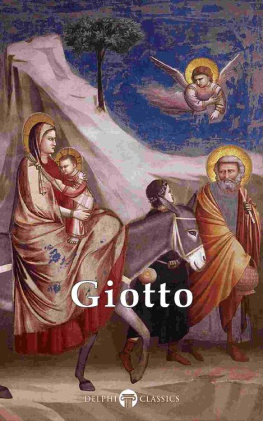

This book has grown out of reflections over many years, in the course of which I have, in lectures and publications, stated some of its themes. Giotto and Dante was the subject of a public lecture at the University of California in 1941.1 also lectured upon Picasso, Painter and Engraver there and at Howard University in Washington, D.C. in 1947. The text of that lecture was later privately printed in an edition of seventy five copies by Adrian Wilson, San Francisco, for Igor Stravinsky, on the occasion of his seventieth birthday (1952). An extract from The Condition of Modern Art and Thought appeared in Scritti di Storia dellArte in onore di Lionello Venturi, edited by de Luca in Rome, 1956.

Contents

Introduction

by Deborah Rosenthal

The writings of Erwin Rosenthal, who died in 1981, are virtually unknown today. Originally published in 1962 by George Wittenbornwho brought to American readers such crucial texts as Mondrians Plastic Art and Pure Plastic Art and Robert Motherwells Dada Painters and PoetsRosenthals The Changing Concept of Reality in Art presents readers with what amounts to a fresh, unexpected voice in a very old discussion about the nature of artistic style. Rosenthals writing has some of the intimacy and freewheeling exploratory spirit of conversations between friends who love art. As he investigates the origin and evolution of artistic style, he moves from art to literature, from psychology to music, reflecting on the sculpture of Henry Moore, the poetry of Mallarm, or the architecture of New York City. Rosenthal sees a tension between two competing views of the origin and evolution of artistic style; he regards the artist both as a prime mover, willing styles into being, and also as the instrument through which more general stylistic shifts are registeredshifts that reflect transformations in culture and society at large.

Rosenthal, who earned a doctorate in medieval art history at Augsburg in 1912, spent his student years near the epicenter of these debates about artistic style, many of which were taking place in Austrian and German universities and museums and in books and articles published in Vienna and Berlin. But in choosing never to pursue an academic career, he ended up standing somewhat apart from these debates as well. Instead, as his granddaughter writes in her biographical note in this edition, he entered the family antiquarian-bookselling firm, and for the rest of his life he worked in that business while writing occasionally on art-historical subjects that interested him. The Changing Concept of Reality in Art, which collects some of Rosenthals historical observations and aesthetic musings, is a meditation on the subject of abstraction and representation. The reality of Rosenthals title consists of everything the artist can feel or experience or perceive, whether that reality is expressed through naturalistic forms or through forms that reject the appearance of the natural world. He invites us into the intimacy of works of art in all their permutations. Moving back and forth through the history of many arts, he reveals the contours of his mind and his personality by distilling parallelisms and polarities within artistic styles; a reader feels the varied aspects of Rosenthals taste. As a scholar, he most often wrote about medieval art. But he was also fascinated by twentieth-century abstraction, the revolutionary art of his youth, which was still evolving in the 1940s, when he gave the occasional lectures at American universities on which some of these essays were based.

Though Rosenthals canvas is large, he works with light touches. There are passages that home in on individual periods, artists, or works of art and crystallize ideas through an apposite quotation, a bit of formal analysis, or a summary of historical phenomena. He frames his discussion with the years 1300 and 1900. He focuses first on the pivotal figures of Giotto and Dante, who were transforming the spiritual, anti-naturalistic expression of the Middle Ages into an art that represents the world as men and women see it. Turning to 1900, he shows how Picasso and his contemporaries reversed that revolution, and restored the possibilities of an abstract art. He takes the reader to the 1937 Paris Worlds Fair to look at etchings by Picasso, and on the same page mentions twelfth-century art from Catalonia; he cites contemporary Japanese art, and recent exhibitions by little-known French artists. He draws parallels between the plastic arts and music and poetry, and touches on philosophy and psychology, at one point reminding the reader of a link between Freud and Virgil. Declaring himself a humanist, he expresses his belief in art as thought, thought as artperhaps deliberately echoing the title of The History of Art as the History of Ideas by Max Dvorak, one of the Viennese academics who had framed the great art-historical questions in Rosenthals student days.

Rosenthals deft sketches of some of the developments in the art of the past seven centuries outline a fundamental duality of abstraction and representation that was already familiar when he published this book. It is hard to imagine that he was not thoroughly familiar with Wilhelm Worringers 1908 Abstraction and Empathy, a German dissertation published, to a very wide reception, a few years before he wrote his own. When Rosenthal in his foreword disclaims any grand dialectical frame and says he is not constructing a psychology of art, he may be thinking of Worringers book, which is subtitled A Contribution to the Psychology of Style. Whatever his sympathy with the touchstones of Worringers theory, his own approach is more open and speculative. For Rosenthal, abstraction and representation are both expressions of reality and both may be present in the imaginations of artists in all times and places. He believes that the artists deep connection with reality, which is nothing less than the sum of his experience, fuels even the geometry, stylization, and reduction of artists who have worked in a non-naturalistic manner throughout the ages. He says that Contemporary art has not, any more than contemporary science, abolished reality but has opened the way to a new concept of what is real. Rosenthal would certainly agree with Paul Klee, who said that the abstract artist makes visible a world.