For Peter Alexander Ring, MS, FRCS , orthopaedic surgeon.

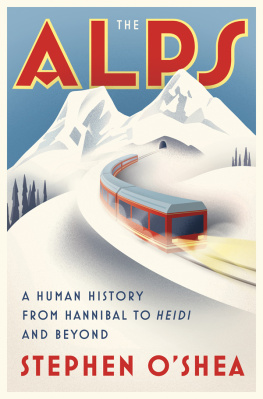

Everybody knows the Alps. Nobody knows how Europes playground became its battlefield.

Virtually from the Fall of France in June 1940 to Hitlers suicide in April 1945, the swastika shadowed the peaks of the Haute-Savoie in the western Alps to the passes above Ljubljana in the east. The Alps as much as Berlin were the heart of the Third Reich. Yes, Hitler declared of his headquarters in the Bavarian Alps, I have a close link to this mountain. Much was done there, came about and ended there; those were the best times of my life My great plans were forged there.

In 1940, Mussolinis troops pitched battle with the French on the Franco-Italian Alpine border, skiing resorts all over the Alps were turned into training centres for mountain warfare, and Switzerland prepared to be invaded. Concentration camps were seeded in the Alpine valleys, Gauleiters were installed in the resorts, and secret rocket factories established; in the southern Alps of Switzerland, St Moritz and Zermatt welcomed escaping Allied PoWs, whilst further north Berne grew fat on looted Nazi gold, and guards turned away Jewish refugees at the countrys borders.

Yet as the war progressed, the occupied Alps became the cradle of resistance to totalitarian rule. Backed by Churchills brainchild, the Special Operations Executive and its US equivalent, the Office for Strategic Services, the mountain terrain spawned the French maquis and the Italian and Yugoslav partisans. From Slovenia to the Savoie, ski-runs became battlegrounds, the upper and lower stations of tlphriques fell to opposing forces, and atrocities were committed with Mausers, bowie knives, mortars and grenades where once winter sports enthusiasts sipped Glhwein. In the spring of 1945, with the Red Army nearing Berlin, Goebbels propagated the myth of the Reichs Alpine Redoubt. Here, Hitler and his diehards would supposedly hold out for years. Eisenhowers armies were diverted south away from the German capital, leaving the city open to Stalin. After the Fhrers death the Allies discovered hoards of looted Nazi treasures, banknotes and bullion secreted in the Bavarian and Austrian Alps.

I was attracted to this story partly because in its entirety it had been told only tangentially and parenthetically before in broader studies of the European war; partly because of the paradox of fascism engulfing such a potent symbol of freedom as the Alps; and partly because of the richness of the personalities it involves, its sheer human drama.

Adolf Hitler, the Luftwaffe chief Hermann Gring, the SS mastermind Heinrich Himmler and the prototypical spin doctor Joseph Goebbels are familiar enough; less so are the Nazis leader in Switzerland Wilhelm Gustloff, the Alpine concentration camp commandant Obersturmfhrer Otto Riemer, and the perpetrator of the Glires tragedy, Waffen-SS Sturmbannfhrer Joseph Darnand. Similarly, the figures of Churchill, Roosevelt and Eisenhower are complemented by the Swiss general Henri Guisan who stepped in where his countrys politicians feared to tread, Conrad OBrien-ffrench (the model for James Bond), the German spy Fritz Kolbe, the hundreds of charismatic Frenchmen who rose above the countrys 1940 fall one of whom rejoiced in the fanciful name of Emmanuel dAstier de la Vigerie and the US spymaster and Don Juan, Allen Welsh Dulles. There are also those with two faces: Josip Broz aka Marshal Tito, the good Nazi Albert Speer, and Frances Charles de Gaulle. The General was the man who accepted such large quantities of Anglo-American blood and treasure resulting in the freeing of his own country with such admirably regal disdain. La France, cest moi!

There were also the everyday people of the Alps drawn by the vortex of fascism into the denouncements, betrayals and atrocities that rendered them inhuman: the agents, above all, of the Holocaust. These were countered by tales of courage, heroism and self-sacrifice, of the ordinary people doing extraordinary things, that characterise conflict wherever and whenever it occurs.

For the Alps, the years under the swastika really were both the best and the worst of times. This is the story that for the first time this book tells.

Burnham Overy Staithe,

June 2013

From this surrender at Berchtesgaden, all else followed.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER

1

On 14 September 1938 an Englishman was getting ready to leave London for the Alps.

There was nothing unusual in this as such, for the English, as well as other Europeans and North Americans, had been seeking adventures in the Alps for more than two hundred years. First as Grand Tourists en route to the classical remains of Italy and Greece; then as scientific travellers, trying to unravel puzzles like the movement of glaciers and the impact of altitude on human physiology; later, in the wake of the Napoleonic wars, as artists. The Romantic poets Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, William Wordsworth had defined Romanticism in their response to the Alps; J. M. W. Turner and Caspar David Friedrich did likewise in paint; Mary Shelley had created Frankenstein on the shores of Lake Geneva. In their wake came the mountaineers who were the first to actually climb the high peaks of Europes great mountain range: from Mont Blanc in the west, the Matterhorn and the Monte Rosa towering above Zermatt, the famous trio of the Eiger, Mnch and Jungfrau in the Bernese Alps high above the Swiss capital of Berne, to the Piz Bernina, the Ortler and the Grossglockner in the east. In the second half of the nineteenth century the clean, dry Alpine air was identified as a palliative and even a cure for tuberculosis. Sufferers from a disease at the time widespread flocked to the mountains for the Alpine cure. Amongst them were Thomas Mann, A. J. A. Symons, Robert Louis Stevenson and the wife of Arthur Conan Doyle, her husband in train. With the coming of the railways, the travel entrepreneurs Thomas Cook and Henry Lunn introduced tourism to the summer Alps. In the early years of the twentieth century, Henrys son Arnold for the first time brought skaters, tobogganers and skiers to the Alps in winter, hitherto closed season. By the outbreak of the First World War a handful of remote villages had won worldwide fame as Alpine holiday resorts. Amongst them were Chamonix, Cortina dAmpezzo, Davos, Grindelwald, Kitzbhel, St Anton, St Moritz, Wengen and Zermatt. After the war skiing established itself as a major international sport, and in 1936 the Bavarian resort of Garmisch-Partenkirchen joined the winners circle as the venue for the Winter Olympics. In an age defined by industrialisation, the Alps had become the playground of Europe. Here the upper and later the middle classes escaped from their dark satanic mills to a purer, older and less material world.

For Switzerland in particular at the heart of the Alps, the English had an affection based on shared liberal constitutional principles and a tradition of personal freedom. Charles Dickens, writing to Walter Savage Landor at the height of the vogue for European revolutions in 1848, declared of the Swiss: They are a thorn in the side of the European despots, and a good and wholesome people to live near Jesuit-ridden kings on the brighter side of the mountains. My hat shall ever be ready to be thrown up, and my glove ever ready to be thrown down for Switzerland! This was echoed in 1878 by Mark Twain:

I met dozens of people, imaginative and unimaginative, cultivated and uncultivated, who had come from far countries and roamed through the Swiss Alps year after year they could not explain why. They had come first, they said, out of idle curiosity, because everybody talked about it; they had come since because they could not help it, and they