ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

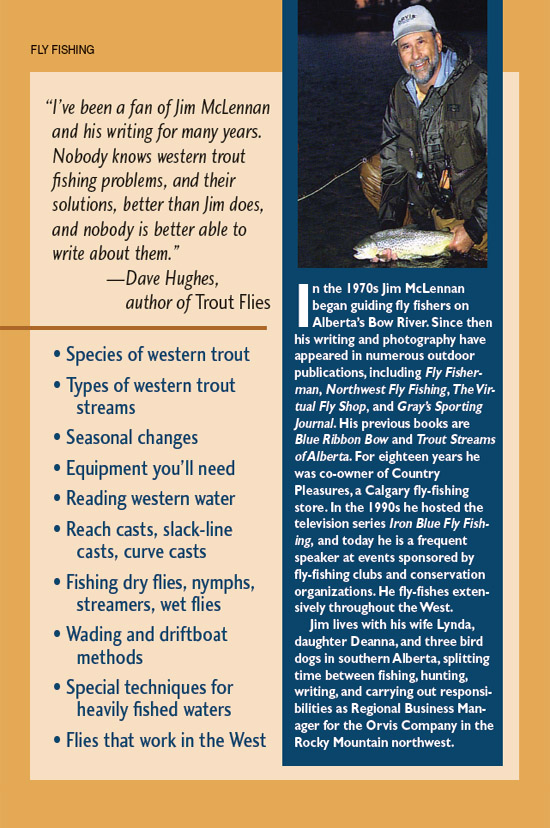

L ike most, this book began as an idea that wouldnt go away. And like all, this book had help with its birth. Near the beginning of the process Dave Hughes, probably the most prolific writer in the history of fly fishing, provided information, inspiration, and advice. From an idea, it became a query, sent to Judith Schnell at Stackpole, who seemed to think it might be possible to turn this pesky idea into a book. Through the rest of the process Judith and Amy Dimeler and the staff at Stackpole were polite, patient, and astute, answering e-mails and directing the books course wisely.

Long-time friend Ross Purnell, of Fly Fisherman magazine, read and commented on parts of the manuscript dealing with tailwater trout streams. George Anderson, of Livingston, Montana, helped with some of the spring creek methods. I leaned heavily on Dave Hughess book Wet Flies for the information on that method of fishing.

I also called on a number of fishing friends for information in the hatch chartsKen Beatty, Chuck Echer, Gary Gould, Tyler Thomas, and Tim Wade.

For help in other ways, thanks to Ken Kohut, Bob Scammell, Jim Gilson, Tim Tollet, and Leigh Perkins. Thanks to Glenn Smith, of Calgary, Alberta, the vise magician whose flies appear in the photographs. Big thanks to my wife, Lynda, for bringing coffee and breakfast on those long mornings in the basement and for sharing western trout streams with me for twenty-five years.

Discover more Fishing books, eBooks, and expert advice from the best in the field

With expert instruction and detailed, step-by-step photos, Stackpoles Fishing titles help advance your skills to the next level.

Visit Stackpole Books Fishing webpage

CHAPTER 1

Western Trout (and Some Relatives)

RAINBOW TROUT

If you were to design the perfect fish for fly fishing, you might end up with a duplication of the rainbow trout. Rainbows possess all the practical and esthetic qualities we want in a sport fish. They live comfortably in streams and lakes and will go to the ocean if theres one handy. They feed heavily on aquatic insects and are happy to do it at the surface of the water. They are beautiful, sleek creatures that, like European sportscars, look fast even when theyre parked. Add the fact that they can be reared quickly and easily in hatcheries, and its not hard to understand why rainbow trout are now favorites of anglers around the world.

What anglers like best about them is their exceptional fighting ability. When hooked, rainbow trout are the uncontested champions of performance. No freshwater fish runs as far, jumps as high or as often. This was made clear to me for the umpteenth time when I fished a small western spring creek a number of years ago. Pale morning dun mayflies were on the water one cloudy, showery afternoon, and the fish were rising to them nicely. They were mostly cutthroats, and I had been having a pretty good day, catching some good-size fish when I did everything just right. At a spot where a gentle run ducked beneath a round, plump willow bush, several good fish were rising, quietly sipping the duns that drifted on the placid surface of the spring creek. I slipped gently into the water downstream of the willow and made a few casts to the nearest fish. After a while, it took my fly. It was an eighteen-inch cutthroat and it thrashed about a bit, but I was able to keep it from disturbing the other fish while I brought it to my net.

The next fish was rising a bit farther back under the willow, and it took several tries to get the cast right. Finally the fly settled like a piece of lint on a billiard table and bobbed along until the head of a trout politely creased the surface to take it. I tightened up gently, congratulating myself for showing restraint and remembering to set the hook with my 6X strike. When the fish felt the prick of the hook, it bolted upstream, ripping the fly line out of my hand. The reel stuttered, the handle stung my knuckles, and the tippet broke about the time the fish reached the shallow water beyond the willow. After breaking off, it jumped, going hard around the next corner, and as it left the water, I saw the pink stripe on its side that explained everything. This was not a bigger fish; it was a different fisha rainbow, just doing its thing.

Few fishermen get confused when rainbow trout are mentioned in a conversation. Other species of fish, especially Pacific salmon, have many localized names that can make it difficult to know just what is being discussed. A taxonomist might disagree, but to most anglers a rainbow is a rainbow is a rainbow, whether it lives in Alaska, Montana, New Zealand, or South America.

Rainbow trout are native to North American waters draining the Pacific Ocean, from Alaska to northern Mexico. With a few exceptions, one being the Athabasca strain in Alberta, they are not native to waters draining the eastern slopes of the Rockies. In general, rainbow trout are spring spawners, though their longtime affiliation with fish hatcheries has allowed human tampering to the point where fall-spawning strains now exist.

The rainbow has been the subject of a classic lumper versus splitter debate among taxonomists for decades. For many years it was believed there were two speciesthe oceangoing rainbow, called steelhead, and the non-migratory stay-at-home version, simply called rainbow. Then the lumpers took the lead, and for a time both migratory and nonmigratory rainbows were called Salmo gairdneri. Its been a seesaw battle, though, and in the 1990s the splitters had their way and steelhead were removed from the rainbow trout list and assigned a new classification, called Oncorhynchus mykiss.

The ease with which rainbow trout eggs and fry can be reared in hatch-eries and transported great distances is the reason they are the most common trout in the West today. In the early days, before the practice of non-native introductions was governed by sound biology and political correctness, fish planting was a make it up as you go proposition. Consequently, migratory and nonmigratory strains of rainbows were mixed, resulting in inconsistent success in establishing rainbows in new waters.

Rainbows were also introduced to many waters already occupied by native cutthroats and bull trout. In some cases, this reduced the stocks or compromised the purity of the native fish. In other cases, rainbows may have accidentally saved the day by giving a stream a species hardier than the natives. In Albertas Bow River, the introduction of rainbows has been a huge blessing, simply because they are more capable than the native cutthroats and bulls of withstanding the pressures caused by the proximity of a major city.

Throughout North America, the heritage of most non-native rainbows can be traced to California and Oregon. Both resident and migratory fish from rivers such as the Rogue and McCloud were used for transplantation as early as 1870. In 1874 fertile California rainbow trout eggs destined for New York State were packed in ice-chilled trays and placed in the bowels of a steamship. Their route was around South America, but the eggs survived, with the result that California rainbow trout reached the eastern United States nine years ahead of European brown trout. The expansion of their range continued, and today there are great rainbow trout fisheries around the world.