Historians are painfully aware of how difficult it is to come by reliable facts in any period of study. And it is not only an historians problem. Those who are in the midst of the events themselves are often as much at a loss for reliable information as those who attempt to reconstruct and interpret events after the fact.

Would the U.S. State Department have instructed April Glaspie , the ambassador to Iraq in 1990, to appear as friendly to Saddam Hussein , to have refrained in their last meeting from warning him against attacking Kuwait, if the United States had known of his plans? Or if the Americans did know Husseins intentions and wanted to lure him to attack so that his nuclear weapons development could be halted, what did George W. Bush s advisors know about their ability to destroy Husseins nuclear capability in the war or its aftermath?

Two professors who taught would-be Washington insiders at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, Richard Neustadt and Ernest May , liked to recall that John F. Kennedy used to tell of hearing in college about a former German chancellor who, when asked the reasons for World War I , replied, Ah, if we only knew.

When the facts are known the trouble does not so much end as begin, for we bring our own interpretive point of view to whatever incomplete facts we may possess, and that point of view may include conscious or unconscious biases. Centuries ago, some believed that earthly events were caused by God, and data was interpreted accordingly. This was regarded as the only correct understanding of the world. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there were those who understood that events and even ideas and feelings arose from the material relationships described by Karl Marx , and histories were written to correspond to that view. Others assumed the truth of Thomas Carlyle s view that historical events were shaped by the acts of great men. In the twenty-first century, most of us have been more comfortable with multifactorial, pluralist explanations that recognize the complexities of a multitude of interacting factors that initiate and give distinctive shape to events. We are especially content if we are able to integrate those factors into a statistically based computer model. We accept that the older views are simply wrong, and our current view is the best possible.

Moreover, we bring to the facts we accumulate certain assumptions buried in language or logic or even our neurological makeup, in the sorts of percepts our minds are able, by their nature, to form. In fact, we make fundamental choices just by placing our facts into a narrative, whether it is a simple narrative of individual actions or a more abstract analysis of historical forces. Historiographer David Lowenthal wrote, No account can recover the past as it was, because the past was not an account, no more, of course, than the present. Both past and present are sets of events and situations about which we compose stories that cannot be understood as definitive any more than a novel can.

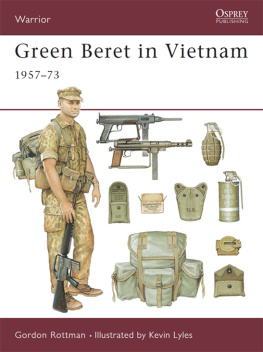

There are numbers of examples of this vexing difficulty of seeing the facts of the matter clearly, by the participants at the time or by those of us who try to reconstruct the event after it occurred. During the Kennedy administration, as Neustadt and May have written, some thought that the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 had been resolved, in part, because of a strategy of graduated escalation in diplomatic maneuvering. Some of these same people, when they served Lyndon Johnson as president, in 1965, thought that graduated escalation would be effective in the Vietnam War . As that strategy was applied, with ever-increasing force, certainty about its effectiveness became elusive and then dissipated.

When the Cold War ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union , many rushed forward to take credit for an American victory. It was confidently said that the Soviet Union was bankrupted because it could not sustain the arms race that the United States economy could afford. George Kennan , who defined the containment policy after World War II, relying on the same facts, wrote that Nobody - country, no party, no person won the Cold War. It was a long and costly political rivalry... It greatly overstrained the economic resources of both countries, leaving both, by the end of the 1980s, confronted with heavy financial, social, and, in the case of the Russians, political problems. Franklyn Holzman, a professor of economics at Tufts University and a fellow at Harvards Russian Research Center, looking at the same evidence as Kennan, wrote, While there is an element of truth in this [explanation of the bankrupting of the Soviet Union by military expenditures], it is not the real explanation... The real causes of the continuously declining growth rate of the Soviet Union, of the poor quality of its products and of its many other deficiencies, are to be found in central planning by direct controls. In short, the Soviet Union would have collapsed without the Cold War, without an arms race. Everyone had the same access to the same broad set of facts - during the Cold War and in retrospect - and intelligent, well-informed people could not agree on what they knew.

Of the many instances of this difficulty of perceiving the historical field as it is, this brief book takes one from the distant past: the meeting between Pope Leo I and Attila the Hun - who, before they met, could not know what they might reasonably hope to achieve; while they were meeting, did not know what they were, in fact, achieving; and after they had met, could not be sure whether they had done anything of lasting significance - any more than we can be certain we know in looking back. Their encounter is an impressive memorial to how little we grasp of the world in which we function.

When Leo the Great, the bishop of Rome, rode out of the Eternal City in the year 452 A.D. to meet Attila the Hun, Leo had no arms, no army, no armor, no bodyguards, no great retinue of ambassadors and advisors, advance men and area specialists, no claque of courtiers, flatterers, or other hangers-on. He went out with only a few fellow churchmen riding alongside him and a couple of lesser officials of the enfeebled and fading Roman Empire.

Attila, the man Leo went to meet, came to the encounter at the head of a large, well-armed, infamously rapacious, battle-hardened army of Huns on horseback: more than 300,000 of them according to some sources, men who had a reputation - at the time, if not among recent, more skeptical scholars - for roasting pregnant women, cutting out the fetus, putting it in a dish, pouring water over it, dipping their weapons into the potion, eating the flesh of children, and drinking the blood of their enemies. They supported themselves, as they rode through the countryside, with pillage and extortion. They ate horsemeat and drank vast amounts of wine. Even the Goths were terrified, according to the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus , when the Hunnish cavalry swept into battle, with dazzling speed, howling and yelling, and dashing in all directions at once.

The Huns, Ammianus said, were almost glued to their horses, which was part of the secret of their success in war. And if Attila followed his usual custom, he did not dismount when he met the pope, but instead stayed on his horse, one leg thrown casually over the horses neck, surrounded by mounted companions, ready to turn and scatter at any moment.

The two men met because Attila and his followers, having plundered the northern Italian peninsula, were on their way south, with the apparent intention of sacking the city of Rome. Leos task was to persuade Attila not to move on down the peninsula and plunder and burn the center of Western civilization.

Geographically, the Roman Empire at this time extended from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean across Europe to the Rhine, the Danube, and the Black Sea. To the north, the empire reached as far as Hadrians Wall in England, and to the south it stretched all the way to Nubia in Africa.

Next page