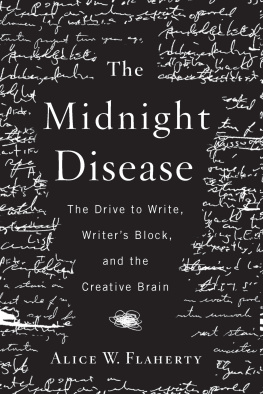

Copyright 2004 by Alice Weaver Flaherty

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Flaherty, Alice W.

The midnight disease : the drive to write, writers block, and the creative brain / Alice W. Flaherty.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-618-23065-3

1. Writers block. 2. AuthorshipPsychological aspects. 3. AuthorsMental health. 4. Creation (Literary, artistic, etc.) I. Title.

PN 171. W 74 F 58 2004

808'.001'9dc21 2003051143

e ISBN 978-0-547-52509-9

v2.0415

To Andrew Hrycyna

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I most want to thank my husband and closest friend, Andrew Hrycynaalso my strictest editorwith whom I had many happily violent arguments about everything from Aristotle to Alice in Wonderland. Katharina Tredes influence permeates the book, with her knowledge (all that European stuff), her nuanced readings, and her ability to keep from categorizing the world too rigidly. Deanne Urmy, my editor at Houghton Mifflin, contributed her literary sensibilities and tolerance, as did my wonderful, warm agent, Mary Evansas sharp a critic as a negotiator.

I am also grateful to Benjamin Davis, Rachel DeWoskin, Nancy Etcoff, C. Miller Fisher (for good advice, Dont tell anyone about it, that I couldnt follow), Ben Greenberg, Alison Hickey (who gave me an Aeolian harp both literarily and literally), Jonathan Rosand (for all things B.C.E. ), Adina Gerver, Patty Gibbons, Ann Graybiel, Esteban Gonzalez, John Herman (knows all the right people, among many other things), Stephen King, Walter Koroshetz (walks on water as a neurologist), Dimitri Krainc, Paul Kafka-Gibbons (great novelists make great critics), Claire LaZebnik (ditto), Kay Redfield Jamison, Scott Liebert (tried to keep me legal), Mia MacCollin, David Perkins, Bruce Quinn, Graham Ramsay (photographer and composer), Mike Rose (remarkable intellectual generosity), Oliver Sacks, Katrin Sadigh, Elaine Scarry, Lee Schwamm, Andrei Shleifer, Ted Stroll (for the most thorough of readings), Janet Taylor, Mike Wiecek, Shirley Wray, and especially Anne Young (who gave me at once freedom and a role model).

Finally, Id like to thank my parents and my sisters, Franklin, Sarah, and Margaret Flaherty (for, among many other things, letting me write at the kitchen table while they washed the Christmas dishes), and my daughters, Katerina and Elizabeth Hrycyna (for providing all the cute twin anecdotes. I hope when theyre teenagers theyll forgive me for having used them).

Introduction

Poets teach us to use words with special force. We may need their help in finding new ways to talk about brains.

J. Z. Young, Programs of the Brain

A creative writer is one for whom writing is a problem.

Roland Barthes, Writing Degree Zero

W RITING IS ONE of the supreme human achievements. No, why should I be reasonable? Writing is the supreme achievement. It is by turns exhilarating and arduous, and trying to write obsesses and distresses students, professional writers, and diarists alike. Writers explain why they write (and have trouble writing) one way; freshman composition teachers, another; literary critics and psychiatrists and neurologists have increasingly foreign explanations. These modes of thinking about the emotions that surround writing do not easily translate into one another. But one fact is always true: the mind that writes is also the brain that writes. And the existence of brain states that affect our creativity raises questions that make us uneasy. What is the relation between mind and body? What are the sources of imagination?

How can both neuroscience and literature bear on the question of what makes writers not only able to, but want to, even need to, write? How can we understand the outpouring of authors such as Joyce Carol Oates or Stephen King? Why does John Updike see a blank sheet of paper as radiant, the sun rising in the morning? (As William Pritchard said of him, He must have had an unpublished thought, but you couldnt tell it.) This compulsion seemsand isan unbelievably complex psychological trait.

Yet it is not so complex that it cannot be studied. Neurologists have found that changes in a specific area of the brain can produce hypergraphiathe medical term for an overpowering desire to write. Thinking in a counterintuitive, neurological way about what drives and frustrates literary creation can suggest new treatments for hypergraphias more common and tormenting opposite, writers block. Both conditions arise from complicated abnormalities of the basic biological drive to communicate. Whereas linguists and most scientists have focused primarily on writings cognitive aspects, this book spends more time exploring the complex relationship between writing and emotion. It draws examples from literature, from my patients, and from some of my own experiences.

Evidence that ranges from Nabokov to neurochemistry, Faulkner to functional brain imaging, shows that thinking about excesses and dearths of writing can also clarify normal literary output and the mechanisms of creativity. The few current books on creativity that include a neuroscientific perspective have neglected crucial brain regions such as the temporal lobe and limbic system in favor of a still-popularbut arguably oversimplifiedemphasis on the role of the right side of the brain.

Focusing on the importance of the brain in the drive to write helps suggest treatments for disorders of creativity that are sometimes medical. It should do so, though, without ignoring the fact that most innovative people, and most people struggling with blocks, are not mentally ill. Concentrating on the brain structures underlying creativity provides surprising answers to such diverse questions as how we learn to write, the nature of metaphor, and even what causes the strange sensation of being visited by the muse.

Although The Midnight Disease attempts to be a scientifically accurate book, it is far from a dispassionate one. How could I speak dryly on a subject as charged as the origin of literature? I am infatuated with writing, and this emotional engagement shapes the book. Writing can do extraordinary things. One night when I was a child, I read a passage in C. S. Lewiss autobiography, Surprised by Joy, which described one of his own reading experiences as a child. He had been reading Longfellows poem Tegners Drapa, when a line jumped out at him: I heard a voice that cried / Balder the beautiful / Is dead, is dead.... The beauty of that line, the way it tore at him, drove him to become permanently addicted to reading and writing. Strangely, even out of context, the line stirred me as well. Something swept me out of his book high into the cold air above the northern wastes. What was it that was transmitted from the writer of Tegners Drapa to the writer of The Allegory of Love to me, possibly even to you?

In her book On Beauty and Being Just, Elaine Scarry imagines Leonardo da Vinci seeing a woman with a face so beautiful that he tries over and over to capture it in different drawings. Later artists are moved by his copies, which they then try to copy themselves. Eventually the critic Walter Pater writes his famous essay on Leonardo, and the copies of the womans face spread from one art form into another. Beauty drives copies of itself, whether in art, or when we want to make children with someone we love. Great scientific ideas drive their own transmission in the same wayit is not a metaphor when researchers refer to an elegant theorem as beautiful.

In another sense, though, it is the brain, not beauty, that drives those copies. Many parts of the brain play a role: Leonardos exquisite motor cortical control of his pen, the way his visual cortex perceived shape from shadow, his face recognition area. Yet some parts of the brain may be more crucial than others for the emotional aspect of the drive toward beauty or meaning.

Next page