Acknowledgments

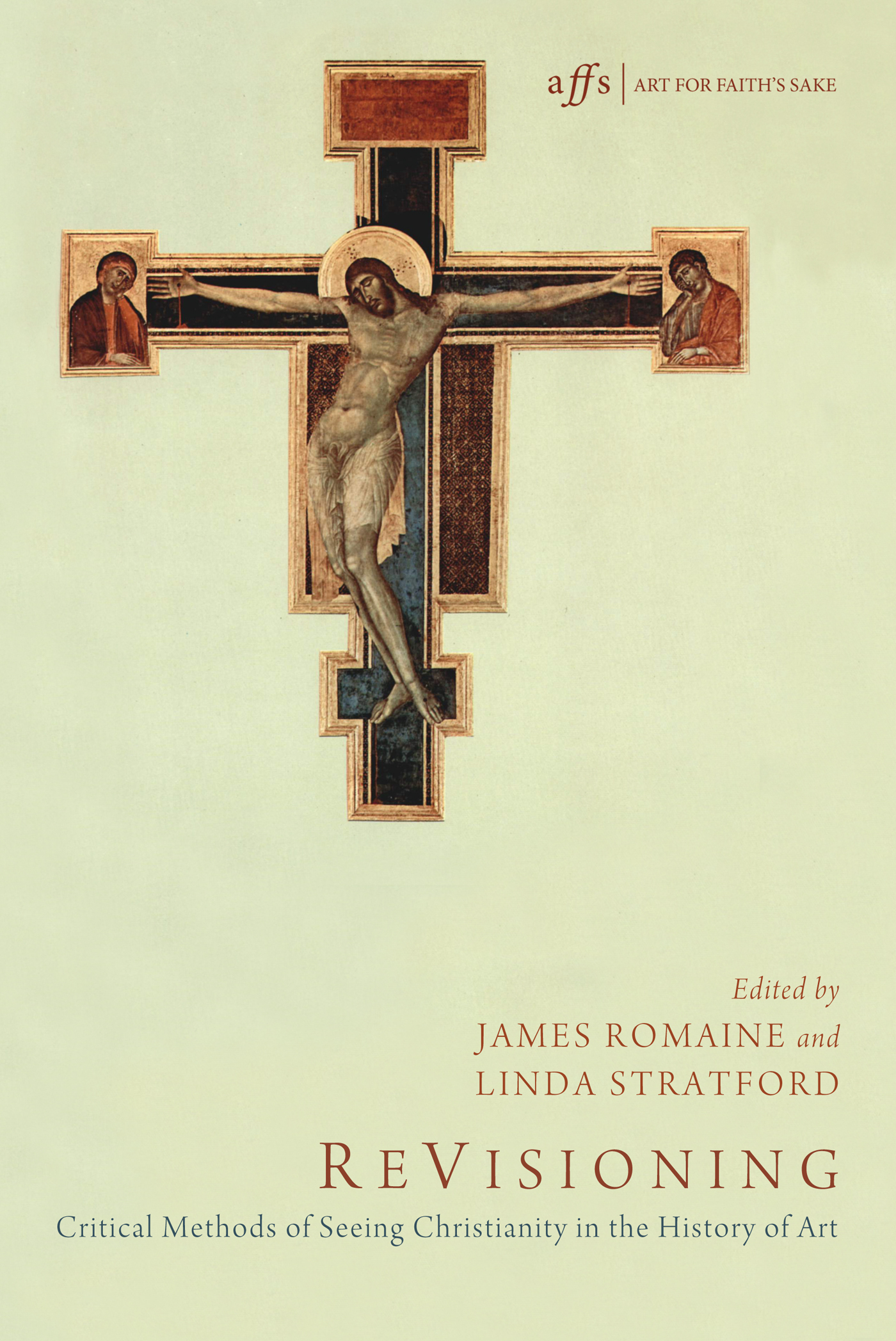

ReVisioning is a project of the Association of Scholars of Christianity in the History of Art (ASCHA). ASCHA has been organized by James Romaine, Linda Stratford, Ronald Bernier, and Rachel Smith. Many of the essays in this volume are based on papers presented at ASCHA symposia. These symposia include History, Continuity, and Rupture: A Symposium on Christianity and Art (Paris, 2010), co-organized by Romaine and Stratford; Why Have There Been No Great Modern Religious Artists? (New York, 2011), co-organized by Romaine and Smith; and Faith, Identity, and History: Representations of Christianity in Modern and Contemporary African American Art (Philadelphia, 2012), co-organized by Nikki A. Greene, Emily Hage, and James Romaine. We are grateful to all of the institutions and scholars who participated in and contributed to these symposia. This book is a record and recognition of the importance of those symposia for the development of methodologies by which the history of Christianity and the visual arts is addressed.

The co-editors are especially grateful to all of the scholars who contributed essays to ReVisioning . Each scholar has contributed something unique to this project. Their scholarship has been made possible by personal and institutional support that cannot all be named here but should not go unrecognized.

We also wish to thank Cascade Books and especially D. Christopher Spinks, editor, for supporting this project. We are grateful to Art for Faiths Sake (AFFS) series editors Clay Schmit and J. Frederick Davison, who along with editors at Cascade reviewed our proposal and selected it for inclusion in AFFS. We are grateful to Heather Carraher for typesetting the manuscript. Susan Cottenden and Erika Graham provided valuable editorial assistance for the project. Mike Peterson offered valuable advice. ReVisioning has been greatly enhanced by the inclusion of color plates. We thank Asbury University for generously funding these color image reproductions, facilitating critical examination of historical methods in tandem with works of art. We also thank Kayce Price and Kerry Geary for their work in photo editing.

We are especially grateful to our institutions, Nyack College and Asbury University, for their support of our scholarship. Finally, we wish to thank our spouses and families for their continual patience while we have faced the pressures of completing a challenging project.

James Romaine

Nyack College

New York, NY

Linda Stratford

Asbury University

Wilmore, KY

Figure 1. Masolino, St. Peter Preaching , 1420s, fresco, altar wall, left side, upper register, Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence. Photo permission of Antonio Quattrone.

Expanding the Discourse on Christianity in the History of Art

James Romaine

The substance, terms, and tone of the art historical discourse are established by the methodologies that scholars employ. These methods shape how and what art history is written and taught. This is true both broadly across the academic field as well as when specifically addressing the history of Christianity and the visual arts. ReVisioning: Critical Methods of Seeing Christianity in the History of Art explores some of the underlying methodological assumptions in the field of art history by examining the suitability and success, as well as the incompatibility and failure, of varying art historical methodologies when applied to works of art that distinctly manifest Christian narratives, themes, motifs, and symbols.

In developing this project, the co-editors looked to several precedents in which the field of art history has engaged in a critical self-examination. One model for this book is Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany , edited by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard . Following that model, this book and the Association of Scholars of Christianity in the History of Art (ASCHA), the organization that initiated this project, are here contributing to further expanding the dialog and the maturation of the discipline of art history by calling to its attention certain methodological attitudes and assumptions that limit the scholarly study of the history of Christianity and the visual arts.

Broude and Garrards introduction articulated a two-part objective, both of which are applicable to ReVisioning . They wrote,

On the most basic and, to date, most visible level, [feminism] has prompted the rediscovery and reevaluation of the achievements of women artists, both past and present. Thanks to the efforts of a growing number of scholars who are devoting their research skills to this area, we know a great deal today about the work of women artists who were almost lost to us little more than a decade ago, as the result of their exclusion from the standard histories.

ASCHA and this book aim to cultivate a community of scholars committed to the recovery of the richness and diversity of the history of Christianity and the visual arts that has been in danger of becoming neglected and invisible.

However, as Broude and Garrard observed, there was/is a larger goal to be accomplished. They wrote, Feminism has raised other even more fundamental questions for art history as a humanistic discipline, questions that are now affecting its functioning at all levels and that may ultimately lead to its redefinition. Broude and Garrards self-consciousness of the theoretical basis of their own practice as well as their act of shining a light onto the methodological assumptions evident in the field at large were both a great contribution to art history and have served as a model for this books attempt to question how art history has addressed, and failed to address, the history of Christianity and the visual arts.

The prevailing narrative of art history is one that charts a movement from the sacred to the secular, progressing out of past historical periods in which works of art were produced to reveal, embrace, and glorify the divine and toward a modern conception of art as materialist and a more recent emphasis on social context. The rise of the academic art historian in the nineteenth century and the development of critical methods of art history, such as connoisseurship, formalism, iconography, psychoanalysis, and semiotics, have been regarded, and even designed, as part of a movement away from matters of personal (and therefore presumed to be subjective) faith toward a critical and rational (and therefore presumed to be objective) discipline. Some recent methods of art history have maintained what has been regarded as a necessary skepticism toward matters of religious faith, presuming that art history and religion, especially Christianity, do not belong together.

In Art History after Modernism , Hans Belting notes that modernism was not only an artistic practice; it was also a paradigm of art history.

In critiquing the secularist assumptions of those methods of art history persisting from the last century, it is advisable, however, not to go too far. In many cases, the development of these art historical methods has contributed positively to the establishment of professional practices. At the same time, these methods have created problems for the field of art history. The history of art, that is, the production of art by artists, has been, is, and is likely to continue to be, largely committed to the creative visualization of faith, spirituality, and religion. Over the last two centuries, artists, not only in Europe and the Americas but throughout the world, have continued to produce works of art with distinctly Christian subjects, forms, and purposes. At the same time, images and objects reflective of Christian content and contexts have too often been met by a field that lacks the methodological framework by which to meaningfully inform their engagement. In some cases, the very structures imposed by these methods secularist assumptions minimize, misconstrue, or marginalize the work of arts Christian content. The effect is a contracting rather than expanding of the experience of looking at art. ReVisioning: Critical Methods of Seeing Christianity in the History of Art contends that scholars ignore the pervasive and influential presence of Christianity in the history of art at the risk of distorting that history. There is today an urgency to develop an open and rigorous discussion of methods by which scholars can constructively engage the history of Christianity and the visual arts, as a benefit not only to that history, but to the very integrity of the field of art history itself.