About the Book

Twenty years ago, Bill Bryson went on a trip around Britain to celebrate the green and kindly island that had become his adopted country. The hilarious book that resulted, Notes from a Small Island, was taken to the nations heart and became the best-selling travel book ever, and was also voted in a BBC poll the book that best represents Britain.

Now, to mark the twentieth anniversary of that modern classic, Bryson makes a brand-new journey around Britain to see what has changed.

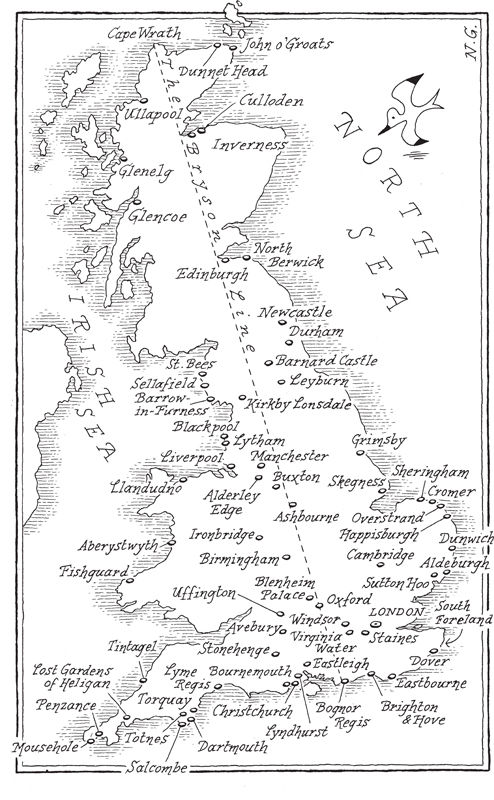

Following (but not too closely) a route he dubs the Bryson Line, from Bognor Regis to Cape Wrath, by way of places that many people never get to at all, Bryson sets out to rediscover the wondrously beautiful, magnificently eccentric, endearingly unique country that he thought he knew but doesnt altogether recognize any more. Yet, despite Britains occasional failings and more or less eternal bewilderments, Bill Bryson is still pleased to call our rainy island home. And not just because of the cream teas, a noble history, and an extra day off at Christmas.

Once again, with his matchless homing instinct for the funniest and quirkiest, his unerring eye for the idiotic, the endearing, the ridiculous and the scandalous, Bryson gives us an acute and perceptive insight into all that is best and worst about Britain today.

Contents

To James, Rosie and Daphne. Welcome.

Prologue

I

ONE OF THE THINGS that happens when you get older is that you discover lots of new ways to hurt yourself. Recently, in France, I was hit square on the head by an automatic parking barrier, something I dont think I could have managed in my younger, more alert years.

There are really only two ways to get hit on the head by a parking barrier. One is to stand underneath a raised barrier and purposely allow it to fall on you. That is the easy way, obviously. The other method and this is where a little diminished mental capacity can go a long way is to forget the barrier you have just seen rise, step into the space it has vacated and stand with lips pursed while considering your next move, and then be taken completely by surprise as it slams down on your head like a sledgehammer on a spike. That is the method I went for.

Let me say right now that this was a serious barrier like a scaffolding pole with momentum and it didnt so much fall as crash back into its cradle. The venue for this adventure in cranial trauma was an open-air car park in a pleasant coastal resort in Normandy called Etretat, not far from Deauville, where my wife and I had gone for a few days. I was alone at this point, however, trying to find my way to a clifftop path at the far side of the car park, but the way was blocked by the barrier, which was too low for a man of my dimensions to duck under and much too high to vault. As I stood hesitating, a car pulled up, the driver took a ticket, the barrier rose and the driver drove on through. This was the moment that I chose to step forward and to stand considering my next move, little realizing that it would be mostly downwards.

Well, I have never been hit so startlingly and hard. Suddenly I was both the most bewildered and relaxed person in France. My legs buckled and folded beneath me and my arms grew so independently lively that I managed to smack myself in the face with my elbows. For the next several minutes my walking was, for the most part, involuntarily sideways. A kindly lady helped me to a bench and gave me a square of chocolate, which I found I was still clutching the next morning. As I sat there, another car passed through and the barrier fell back into place with a reverberating clang. It seemed impossible that I could have survived such a violent blow. But then, because I am a little paranoid and given to private histrionics, I became convinced that I had in fact sustained grave internal injuries, which had not yet revealed themselves. Blood was pooling inside my head, like a slowly filling bath, and at some point soon my eyes would roll upwards, I would issue a dull groan, and quietly tip over, never to rise again.

The positive side of thinking you are about to die is that it does make you glad of the little life that is left to you. I spent most of the following three days gazing appreciatively at Deauville, admiring its tidiness and wealth, going for long walks along its beach and promenade or just sitting and watching the rolling sea and blue sky. Deauville is a very fine town. There are far worse places to tip over.

One afternoon as my wife and I sat on a bench facing the English Channel, I said to her, in my new reflective mood, I bet whatever seaside town is directly opposite on the English side will be depressed and struggling, while Deauville remains well off and lovely. Why is that, do you suppose?

No idea, my wife said. She was reading a novel and didnt accept that I was about to die.

What is opposite us? I asked.

No idea, she said and turned a page.

Weymouth?

No idea.

Hove maybe?

Which part of no idea are you struggling to get on top of?

I looked on her smartphone. (Im not allowed a smartphone of my own because I would lose it.) I dont know how accurate her maps are they often urge us to go to Michigan or California when we are looking for some place in Worcestershire but the name that came up on the screen was Bognor Regis.

I didnt think anything of this at the time, but soon it would come to seem almost prophetic.

II

I first came to England at the other end of my life, when I was still quite young, just twenty.

In those days, for a short but intensive period, a very high proportion of all in the world that was worth taking note of came out of Britain. The Beatles, James Bond, Mary Quant and miniskirts, Twiggy and Justin de Villeneuve, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylors love life, Princess Margarets love life, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, suit jackets without collars, television series like The Avengers and The Prisoner, spy novels by John le Carr and Len Deighton, Marianne Faithfull and Dusty Springfield, quirky movies starring David Hemmings and Terence Stamp that we didnt quite get in Iowa, Harold Pinter plays that we didnt get at all, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, That Was the Week That Was, the Profumo scandal practically everything really.

Advertisements in magazines like the New Yorker and Esquire were full of British products in a way they never would be again Gilbeys and Tanqueray gin, Harris tweeds, BOAC airliners, Aquascutum suits and Viyella shirts, Keens felted hats, Alan Paine sweaters, Daks trousers, MG and Austin Healey sports cars, a hundred varieties of Scotch whisky. It was clear that if you wanted quality and suavity in your life, it was British goods that were in large part going to supply it. Not all of this made a great deal of sense even then, it must be said. A popular cologne of the day was called Pub. I am not at all sure what resonances that was supposed to evoke. I have been drinking in England for forty years and I cant say that I have ever encountered anything in a pub that I would want to rub on my face.

Because of all the attention we gave Britain, I thought I knew a fair amount about the place, but I quickly discovered upon arriving that I was very wrong. I couldnt even speak my own language there. In the first few days, I failed to distinguish between