This book made available by the Internet Archive.

To

Ernest J. DeSalvo

Acknowledgments

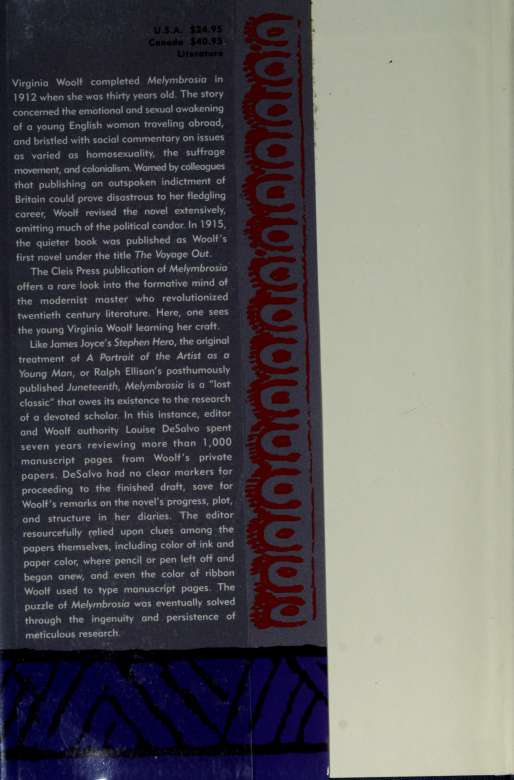

I would like to thank Frederique Delacoste at Cleis Press for her enthusiasm for publishing this edition of Melymbrosia. I am grateful to Felice Newman for her careful reading of the introduction to this edition. Thanks, too, to Don Weise for the energy that he has brought to this, and other projects.

I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to Edvige Giunta, who provides the kind of support that permits a writer to keep working. I thank Hunter College President, Jennifer J. Raab for her unwavering support of my work and for revitalizing Hunter College with the challenges of a new century in mind. I thank, too, Acting Provost, Ann Cohen, Acting Associate Provost, Vita Rabinowitz, Dean Robert Marino, Professor Richard Barickman, Chair of the Department of English at Hunter College and Professor Harriet Luria, Deputy Chair.

Ernest J. DeSalvo first persuaded me that editing Melymbrosia would be worthwhile; I thank him for all the help he has provided during the production of this volume. Frederick B. Adams, Jr., David V. Erdman, Alice Fox, James W. Haule, Elizabeth Heine, W. Speed Hill, Mitchell A. Leaska, Jane Lilienfeld, Jane Marcus, the Modern Language Association's Committee on Scholarly Editions, David J. Nordloh, Susan M. Squier, Lola L. Szladits, and G. Thomas Tanselle, were all enormously helpful with work on the original volume.

I would like to thank Isaac Gerwitz, Curator of the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection. And finally, I would like to express my gratitude to the Author's Literary Estate for permission to produce this volume, and to Elizabeth Haylett for her help and her enthusiasm for the publication of this edition.

Contents

Introduction page ix

A Note to the Reader . page xxviii

"A Wound in My Heart"

Virginia Stephen and the Writing of Melymbrosia

In June 1910, Virginia Stephen entered a nursing-home at Twickenham for a rest cure. She had not been well since March, when she was finishing the draft of her first novel, Melymbrosia, presented in this volume. The completion of major projects would always be a dangerous time for her throughout her writing life. Near the end of her work on The Years, for example, she succumbed to suicidal despair, blaming her disintegration on the book. She had been working at a frenetic pace and was feeling overwhelmed and stressed. This time, the tumult of a flirtatious relationship with Clive Bell, her sister Vanessa's husband, and Virginia's guilty feelings about the affair, complicated the final stage of her work on Melymbrosia.

There has been much speculation about the causes of Virginia Woolf s depressions and mental breakdowns throughout her life. That she was sexually abused in 1888 at age six by her half-brother Gerald Duckworth and, later, when she was a teenager through 1904 when she was in her twenties, both by him and her other half-brother George, is surely supremely important.

In a memoir, "22 Hyde Park Gate," read aloud to friends in the 1920s, Virginia Woolf publicly described how, as a very young woman, she would undress for bed, and,

almost asleep, she would hear the creaking of her door. George Duckworth would enter her room and implore her not to turn on the light. "Beloved," he would say, as he "flung himself" onto her bed and took her in his arms. But, Woolf said, no one in her family's privileged circle in London knew that George was not only brother, but also "lover" of both her and her sister Vanessa. Virginia Woolf, one of the twentieth century's greatest novelists, was an incest survivor.

Her breakdowns, then, can be understood as evidence that she suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. Woolf had many of its symptomsperiods of overwhelming sorrow; mental anguish; negative feelings about her body; feelings of emotional coldness, emptiness, and detachment; sleep disturbances; inexplicable headaches; food disorders; fear, anxiety, and mistrust. And her heroine, Rachel Vinrace, in Melymbrosia, also manifests several of these symptoms.

Virginia Stephen was born on January 25, 1882, into a household in which incest, sexual abuse, physical violence, and verbal abuse towards girls and young women were common. In contemporary parlance, the Stephen family was extremely dysfunctional. Like many writers who achieve fame, her initial impulse to create was fueled by loss, grief, and sexual abuse. These experiences form the emotional bedrock of her first novel.

Virginia Stephen envisioned the kind of novel that she would write one day almost immediately after the death of her father in February 1904. The inspiration for Melymbrosia can be traced to this time, although there is no evidence that she began working on the novel this early. She was writing reviews and essays, but she now started thinking about a project sufficiently lengthy and compelling to take her mind away from her father's death.

The loss of Virginia's brother Thoby Stephen in 1906 also contributed to the novel. After his death, Virginia wandered the streets of London in grief chanting lines from Alfred Lord Tennyson's In Memoriam. For years, Thoby had been her intellectual companion, the sibling with whom she had discussed Shakespeare and the Greeks, who showed respect for the quickness of her mind. With him, she first engaged in equally matched, heated intellectual debates. In losing Thoby, she lost the person who provided her with access to the world beyond her Victorian household, the home to which she had been largely confined (much like her heroine Rachel) by both social custom and frequent illness.

Thoby had contracted typhoid on a holiday the family took in Greece. Virginia became responsible for his care because Vanessa and a family friend, Violet Dickinson, were also ill. Virginia, though she believed her brother's doctor was incompetent (as Terence Hewet believes that Rachel's doctor is in Melymbrosia) , was persuaded by him not to consult another. But the doctor misdiagnosed Thoby s typhoid as pneumonia and there was a botched operation as well.

Virginia blamed herself for his death, and she wished she had died instead. In one sense, because her heroine shares so many of her character traits, Rachel's death in Melymbrosia can be read as a symbolic substitute of her own death for that of Thoby s. And Virginia surely drew upon this event in writing Rachel's deathbed scenes late in the novel.

Virginia's sister Vanessa agreed to marry Clive Bell only two days after Thoby s death. After their marriage, the couple moved into the house that Vanessa, Virginia, Thoby, and her younger brother Adrian had shared, displacing Virginia, and forcing her to share accommodations with Adrian, with whom she did not get along.

~ xi ~

Virginia was furious that Clive had taken her sister away from her by marrying. She expressed her rage at Vanessa by trying to steal her husband's affections. After the birth of Vanessa and Clive s first child, she and Clive carried on what was perhaps the most passionate heterosexual relationship of Woolf's life. It was dangerous and self-destructive, however, for it alienated her from her sister Vanessa's attentions which she counted on for emotional sustenance.