AMERICAN POETS PROJECT

IS PUBLISHED WITH A GIFT IN MEMORY OF

James Merrill

AND SUPPORT FROM ITS FOUNDING PATRONS

Sidney J. Weinberg, Jr. Foundation The Berkley Foundation Richard B. Fisher and Jeanne Donovan Fisher Introduction, volume compilation, and notes copyright 2005 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission. Copyright 1944, 1945, 1949, 1959, 1960, 1963, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1975, 1980, 1986, 1991 by Gwendolyn Brooks Blakely. Copyright 2003 by Nora Brooks Blakely. For permissions, write to Brooks Permissions, P.O. Box 19355, Chicago, IL 60619. Design by Chip Kidd and Mark Melnick.

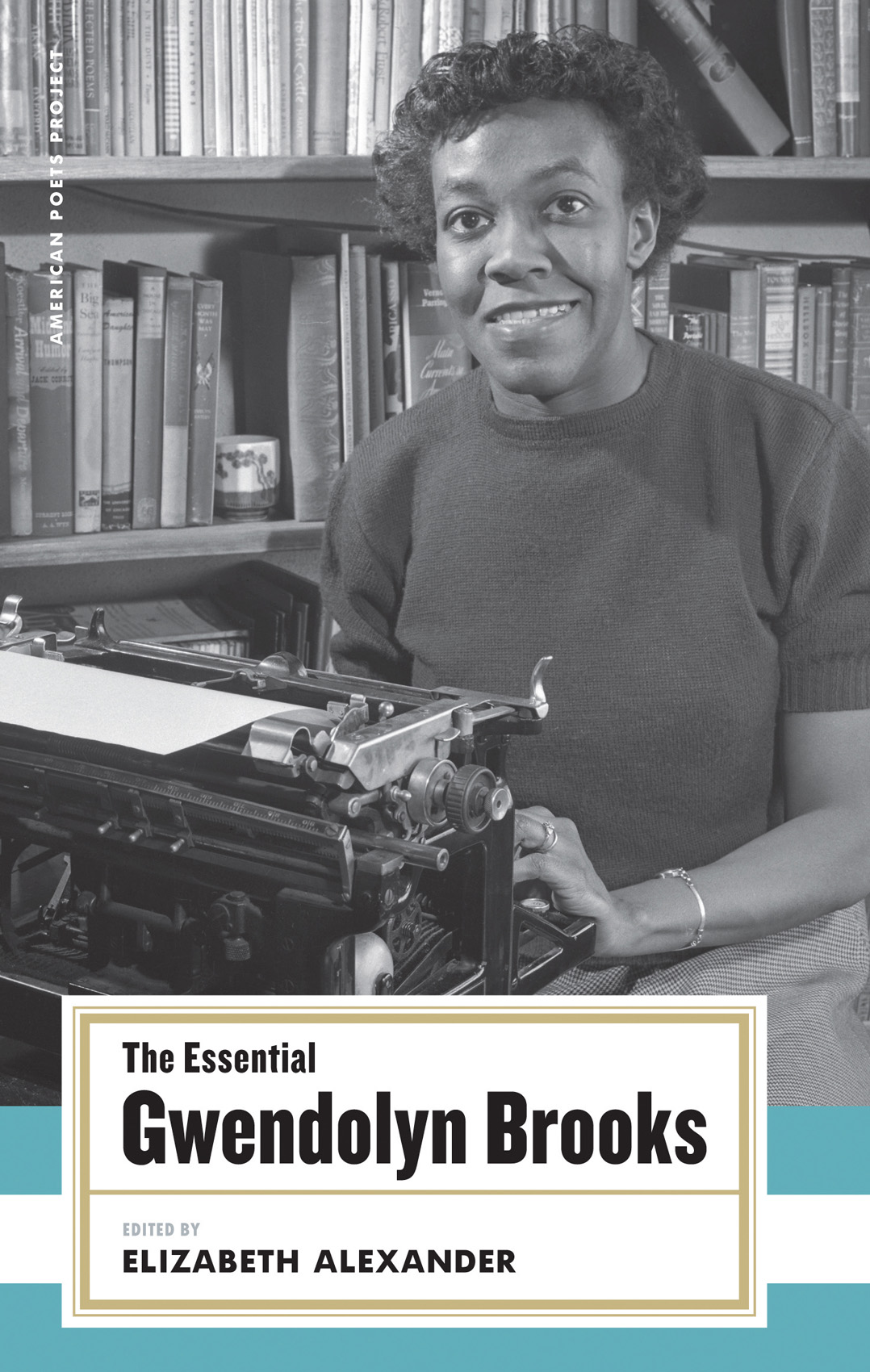

Frontispiece: Gwendolyn Brooks, ca. 1972; Bettmann/CORBIS THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of Americas best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen. If you would like to request a free catalog and find out more about The Library of America, please visit with your name and address. Include your e-mail address if you would like to receive our occasional newsletter with items of interest to readers of classic American literature and exclusive interviews with Library of America authors and editors (we will never share your e-mail address). [Poems. [Poems.

Selections] The Essential Gwendolyn Brooks ; Elizabeth Alexander, editor. p. cm. (American poets project ; 19) ISBN 1931082871 (alk. paper) ISBN 9781598533248 (epub) I. Title. III. Series. Series.

PS3503.R7244A6 2005

Gwendolyn Brooks

INTRODUCTION

Since she began publishing her tight lyrics of Chicagos great South Side in the 1940s, Gwendolyn Brooks has been one of the most influential American poets of the twentieth century. Her poems distill the very best aspects of Modernist style with the sounds and shapes of various African-American forms and idioms. Brooks is a consummate portraitist who found worlds in the community she wrote out of, and her innovations as a sonneteer remain an inspiration to more than one generation of poets who have come after her. Her career as a whole also offers an example of an artist who was willing to respond and evolve in the face of the dramatic historical, political, and aesthetic changes and challenges she lived through. Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks was born in 1917 in Topeka, Kansas, the daughter of Keziah Wims Brooks and David Anderson Brooks. Her father aspired to be a doctor and studied medicine for a year and a half at Fisk, but ended up working as a janitor.

He was the son of a runaway slave. Her mother was a teacher before her marriage and then turned her full attention to homemaking, attending fiercely to the creative talent of young Gwendolyn from an early age. Her mother would tell her that she was going to be the lady Paul Laurence Dunbar. The family moved to Chicago shortly after Brookss birth, and she would spend the rest of her life on that citys South Sidea great Negro metropolisthrough years when the innovation, strength, struggle, and vision of its black residents gave her a backdrop and context for all that would interest her in her work. The Chicago of Brookss formative years bustled with creative and political energy. Black Southern migrants from the second wave of the Great Migration flocked to the city in large numbers.

In 1936, Harlem was the only neighborhood in the United States with a larger black population than Chicagos South Side. For many of the Chicago characters in Brookss poems, as well as its real-life residents, the rural South was close at hand in memory and ways even as people navigated the rough and ready wind-whipped city. The South represented the beauty of home ways, but it was also the economically, spiritually, and physically violent home of white supremacy. In 1935, the WPA Federal Writers Project began, and Chicago was a hive of subsidized artistic activity that often dovetailed with progressive interracial (if problematically so) political movements. More artists participated in the Federal Writers Project in Chicago than in any other city in the United States. In 1936, the novelist Richard Wright formed the South Side Writers group that included poets Frank Marshall Davis and Margaret Walker, playwright Theodore Ward, and the admired poet-critic Edward Bland, who died in World War II and whom Brooks memorialized in a poem.

In the flourishing years from 1935 to the end of World War II, Chicago was home at various times to a collection of creative people that rivaled the Harlem Renaissance. There were artists such as Charles Sebree, Eldzier Cortor, Charles White, Elizabeth Catlett, Gordon Parks, Hughie Lee-Smith, Archibald Motley, and writers such as Wright, Walker, Davis, Fenton Johnson, Margaret Cunningham Danner, Margaret Burroughs, Bernard Goss, Arna Bontemps, Frank Yerby, Marita Bonner, and Willard Motley. Dancer Katherine Dunham was finishing her studies in anthropology at the University of Chicago. Paul Robeson and Langston Hughes would frequently pass through and connect with that crowd. Claude McKay attended the publication party for Brookss first book. In the first installment of her autobiography, Report From Part One, Brooks describes the exciting social life that she and her husband, Henry, enjoyed in the early 1940s: My husband and I knew writers, knew painters, knew pianists and dancers and actresses, knew photographers galore.

There were always weekend parties to be attended where we merry Bronzevillians could find each other and earnestly philosophize sometimes on into the dawn, over martinis and Scotch and coffee and an ample buffet. Great social decisions were reached. Great solutions for great problems were provided.... Of course, in that time, it was believed, still, that the society could be prettied, quieted, cradled, sweetened, if only people talked enough, glared at each other yearningly enough, waited enough. The black press was also a powerful force. John Sengstacke was building the Chicago Defender into the most noted black paper in the country, where one could regularly read cutting-edge political news, poetry, and the column by Langston Hughes which began in 1942.

John Johnson, who went on to found and publish Jet, Ebony, Sepia, and Negro Digest/Black World, under the aegis of his Johnson Publications, was in a writers group with Brooks. Brooks attended junior college, began working, and soon married Henry Blakely, who was also a poet. They were both intensely devoted to their work, though like most poets they did other work for money. Their first child, Henry Jr., was born in 1940. In 1941, Brooks joined a poetry workshop organized by a wealthy white woman, Inez Cunningham Stark, who had been the president of the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago and had helped bring the likes of Leger, Prokofiev, and Le Corbusier to the city. Stark also had a long affiliation with Poetry, one of the most influential literary magazines of its time.

In Starks all-black workshop, held in the South Shore Community Center, writers studied Modernist poets and rigorously critiqued one anothers work. In Brookss teenage correspondence with James Weldon Johnson (whose 1922 and 1931 editions of the Book of American Negro Poetry