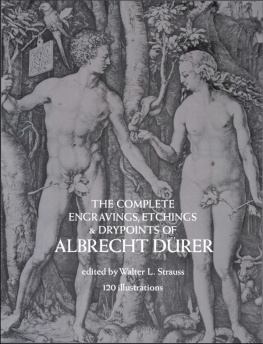

THE COMPLETE

ENGRAVINGS,

ETCHINGS AND

DRYPOINTS OF

Albrecht Drer

THE COMPLETE

ENGRAVINGS,

ETCHINGS AND

DRYPOINTS OF

Albrecht Drer

Edited by Walter L. Strauss

___________________________________________________________________________

DOVER PUBLICATIONS INC.

NEW YORK

Copyright 1972, 1973 by Dover Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved.

The Complete Engravings , Etchings and Drypoints of Albrecht Drer is a new work, first published by Dover Publications, Inc., in 1972.

Second edition, 1973.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-189347

International Standard Book Number

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-22851-8

ISBN-10: 0-486-22851-7

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

22851715

www.doverpublications.com

CONTENTS

The merchants of Italy, France and Spain are purchasing Drers engravings as models for the painters of their homelands

[Johannes Cochlaeus, Cosmographia Pomponij Mele , Nuremberg, 1512].

The entire world was astonished by his mastery

[Giorgio Vasari, Vite de pi eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori , Florence, 1568].

Drers contemporaries were already fascinated by his engravings. The esteem in which they have been held ever since is exemplified by Vasaris remarks, made forty years after Drers death by an Italian in Italy, the country which thought it had a monopoly in the arts.

Apart from the mastery of execution, this admiration of Drer has frequently been attributed to his versatility and to the large number of works in all media which have come down to us. These consist of some 2000 drawings, 250 woodcuts, more than seventy paintings, three books on theoretical subjects and over one hundred engravings.

There are indeed other artists who have left us legacies of similar magnitude, novelty and mastery. The reason for the peculiar fascination exercised by the body of Drers work goes beyond this, however, and must be sought elsewhere.

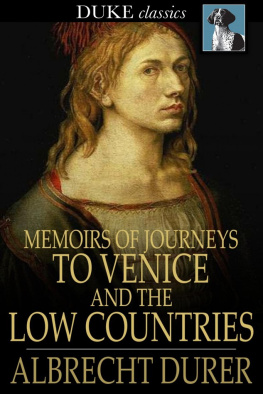

Drer never stood still. He innovated and experimented to the end of his life. Even during his sojourn at Basel as a journeyman, he introduced an effervescent new element into woodcut book illustration. But only a few years later, at Venice, the center of book publishing, he was engaged in other pursuits.

Upon his return to his native city of Nuremberg, he carried with him a portfolio of water-color landscapes made at a time when landscape painting was unknown. These sketches strike us even today as thoroughly modern.

In Nuremberg he then established his fame with the publication of a series of extra-large woodcuts illustrating the Revelation of St. John the Divine, known as The Apocalypse . It was the first book both illustrated and published by an artist. The text is therefore subordinate to the pictures, but these are revolutionary and drastically different in concept and execution from anything seen before.

Shortly after this Drer became interested in the theory of the proportion of the human body. He embarked upon experimentation with constructed faces and figures, culminating in the engraved Adam and Eve of 1504. Only three years later, in 1507, in the painted version of the same subject, the constructed system has given way to idealization.

During 1506 Drer went to Italy a second time. Evidence of the change that came over him is found in the letter of February 7 to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer: The works which pleased me eleven years ago no longer appeal to me. If I had not seen it for myself, I would not have believed anyone who told me such a thing.

In Italy, Drers Brotherhood of the Rosary amazed the Venetian painters. Drer had meticulously alternated numerous layers of color and transparent varnish in order to achieve an unprecedented iridescent effect. Upon his return to Germany he painted a few more commissioned panels, but then abandoned this medium for several years.

In one of his letters Drer mentions his intention of traveling to Bologna for the purpose of learning more about the secret art of perspective. In 1509, the publication at Nuremberg of a plagiarized version of Viators De Perspectiva apparently intensified his interest. His lines suddenly become ruler-straight and the near point of sight is clearly indicated in drawings of this period.

Parallel with these developments, Drer experimented with color. The portrait of Frederick the Wise of Saxony is in sober shades of black and olive, that of Oswald Krell has a bright red background, the St. Onuphrius is in shades of brown and tan, and there are unusual color combinations in the costume studies of Livonian ladies and Irish warriors. But near the end of his life, as reported by Melanchthon, Drer abandoned the lively and radiant colors he had favored in his youth. He realized that simplicity was the highest form of art and no longer admired his own paintings, as had been his wont, but sighed now that he recognized his shortcomings (P. Melanchthon to Georg von Anhalt, December 17, 1546).

After Drers return from the journey to the Netherlands, 1520/21, his works became more sparse, restricted mostly to portrait commissions and printed memorial portraits of his friends. This is perhaps not primarily due to sickness and fatigue, as has frequently been asserted. Drer was then actively engaged in the preparation of his three theoretical works On Measurement, On Fortification and On Human Proportion . The four volumes of manuscripts at London and the papers at Dresden give an indication of the immense amount of time and detailed work expended on these projects. He continued experimentation to the very end. Even the final pages of the fourth book on human proportion, which Drer could no longer edit before his death, comprise an attempt to find a new method of stereometric demonstration of movement. Pirckheimer, who saw to the publication, included these last illustrations without text. Only Drer could have supplied it.

Viewed against this tapestry of experimentationso coarsely woven in the preceding paragraphsexperimentation that encompassed technique, color, perspective and proportion, Drers engravings represent the quintessence of his efforts and thoughts and most succinctly demonstrate the development of this profoundly intellectual artist.

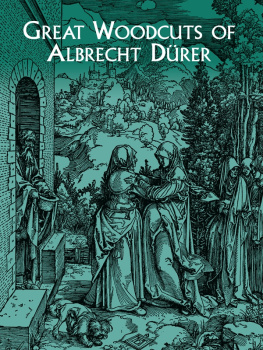

In the case of woodcuts, Drer more often than not simply provided sketches which were then cut into the wood block by skilled artisans. These woodcuts, particularly exemplified by the various Passion series, are simple, direct, outspoken and emotional, marked by an economy of line. The engravings, however, by the very nature of the medium, are entirely his own handiwork. The impression of each fine line is dependent upon the degree of pressure on the burin in the hand of the artist. Drers engravings, in spite of their wealth of detail, are erudite and, at the same time, subtle understatements directed toward a more sophisticated audience. It is here that Drer demonstrates to the world what can be achieved in black and white. These prints are no longer an invitation to add color, like so many of the woodcuts of the fifteenth century.

Engravings, unlike woodcuts, were generally unsuitable as book illustrations. The process of inking and then wiping the plate was too tedious for that purpose. Drer conceived his engravings as individual works of art. At the same time, he was fully conscious of the advantage, commercial and otherwise, of being able to reproduce them in limited editions.

In a letter to Jacob Heller he stresses the importance of selling a picture to Frankfurt, even if he could obtain a higher price elsewhere, because more people will be able to see it there. In another communication Drer asserts that he will no longer accept commissions for paintings with many figures and will return to engraving, for it is much more profitable.

The subject matter of many of his engravings follows this dictum. A great number of his prints are devotional sheets which his wife Agnes sold at the market square of Nuremberg or at the fairs at Frankfurt and other cities. Others are peasant scenes typical of the quaint outdoor types who attended these events as vendors or as buyers. They may well be engraved snapshots of particular individuals who were seen regularly in the marketplace and whom everyone in town recognized.

Next page