Fractured

Times

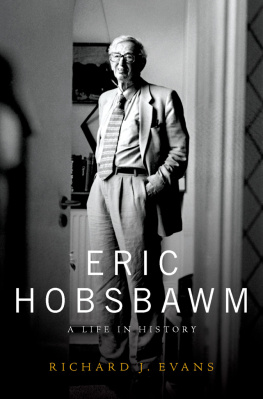

ALSO BY ERIC HOBSBAWM

The Age of Revolution 17891848

The Age of Capital 18481875

The Age of Empire 18751914

The Age of Extremes 19141991

Labouring Men

Industry and Empire

Bandits

Revolutionaries

Worlds of Labour

Nations and Nationalism Since 1780

On History

On the Edge of the New Century

Uncommon People

The New Century

Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism

How to Change the World

On Empire

Interesting Times

2013 by Bruce Hunter and Christopher Wrigley

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Little, Brown Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2014 Distributed by Perseus Distribution

CIP data is available

ISBN 978-1-59558-992-7 (e-book)

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design by M Rules

This book was set in Baskerville

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Contents

I would like to express my gratitude to the Salzburg Festival, and especially its President Mrs Helga Rabl-Stadler and to Prof Heinrich Fischer of Salzburg University, to the London Review of Books where several of the chapters first appeared, to Rosalind Kelly, Lucy Dow and Ze Sutherland who assisted in the research and editing and to Christine Shuttleworth for excellent translations. I also apologise to Marlene for concentrating more intensely than I should have done on the work on this book.

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Matthew Arnold, Dover Beach

This is a book about what happened to the art and culture of bourgeois society after that society had vanished with the generation after 1914, never to return. It is about one aspect of the all-embracing seismic change humanity has been living through since the Middle Ages ended suddenly in the 1950s for 80 per cent of the globe, and about the 1960s, when the rules and conventions that had governed human relations visibly frayed for the rest. It is consequently also a book about an era of history that has lost its bearings, and which in the early years of the new millennium looks forward with more troubled perplexity than I recall in a long lifetime, guideless and mapless, to an unrecognisable future. Having thought and written from time to time as a historian about the curious intertwining of social reality and art, towards the end of the last century I found myself being asked to talk about it (sceptically) by the organisers of the annual Salzburg Festival, a notable survival of The World of Yesterday of Stefan Zweig, who was very much associated with it. These Salzburg lectures form the starting point of the present book, written between 1964 and 2012. More than half of its content has never been published before, at least in English.

are about this world, essentially shaped in nineteenth-century Europe, which created not only the basic canon of classics, especially in music, opera, ballet and drama, but also in many countries the basic language of modern literature. My examples are mainly taken from the region that forms my own cultural background geographically central Europe, linguistically German but they also pay attention to the crucial Indian summer or belle poque of that culture in the last decades before 1914. It ends with a consideration of its heritage.

Few pages are more familiar today than Karl Marxs prophetic description of the economic and social consequences of Western capitalist industrialisation. But as in the nineteenth century European capitalism established its domination over a globe it was destined to transform by conquest, technical superiority and the globalisation of its economy, it also carried with it a powerful prestigious cargo of beliefs and values, which it naturally assumed superior to others. Let us call these the European bourgeois civilisation that never recovered from the First World War. The arts and sciences were as central as belief in progress and education to this self-confident world-view, and indeed were the spiritual core that replaced traditional religion. I was born and brought up in this bourgeois civilisation, dramatically symbolised by the great ring of mid-century public buildings surrounding the old medieval and imperial centre of Vienna: the Stock Exchange, the university, the Burgtheater, the monumental City Hall, the classical Parliament, the titanic museums of art history and natural history facing each other and, of course, the heart of every self-respecting nineteenth-century bourgeois city, the Grand Opera. These were the places where cultured people worshipped at the altars of culture and the arts. A nineteenth-century church was added in the background only as a belated concession to the link between Church and emperor.

Novel as it was, this cultural scene was deeply rooted in the old princely, royal and ecclesiastical cultures before the French Revolution, that is to say, in the world of power and extreme wealth, the quintessential patrons of the high arts and displays. It still survives to a significant extent through this association of traditional prestige and financial power, demonstrated in public show, but no longer hedged by the socially accepted aura of birth or spiritual authority. This may be one reason why it has survived the relative decline of Europe to remain the quintessential expression anywhere in the world of a culture combining power and free spending with high social prestige. To this extent the high arts, like champagne, remain Eurocentric even on a globalised planet.

This section of the book concludes with some reflections on the heritage of this period and the problems it faces.

How could the twentieth century confront the breakdown of traditional bourgeois society and the values that held it together? This is the subject of the eight chapters of the third section of the book, a set of intellectual and counter-intellectual reactions to the end of an era. Among other matters these consider the impact of the twentieth-century sciences on a civilisation that, however devoted to progress, could not understand them and was undermined by them; the curious dialectics of public religion in an era of accelerating secularisation, and of arts that had lost their old bearings but failed to find new ones either through their own modernist or avant-garde search for progress in competition with technology or through alliance with power or, finally, via a disillusioned and resentful submission to the market.

Next page