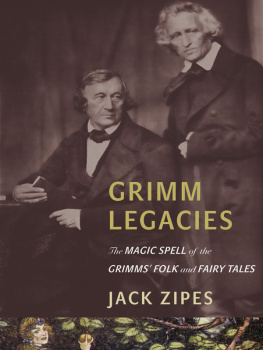

GRIMM LEGACIES

GRIMM LEGACIES

The Magic Spell of the Grimms Folk and Fairy Tales

Jack Zipes

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

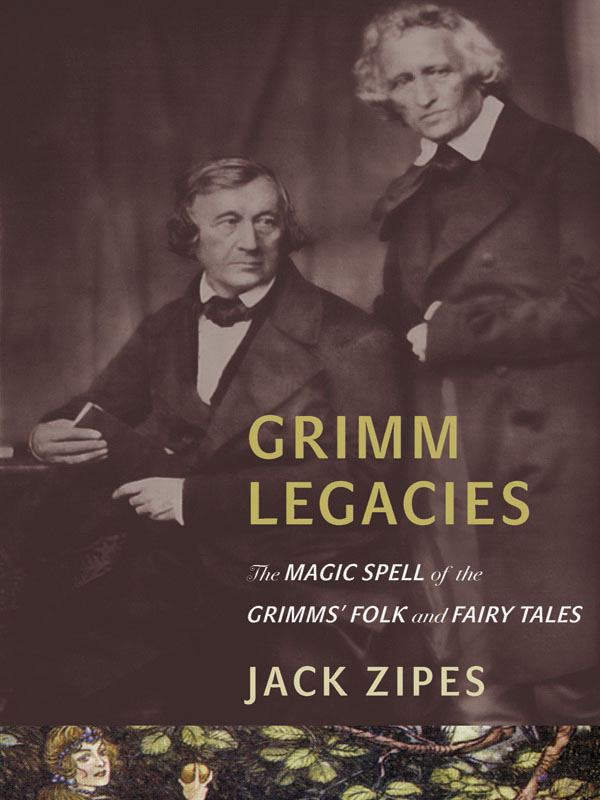

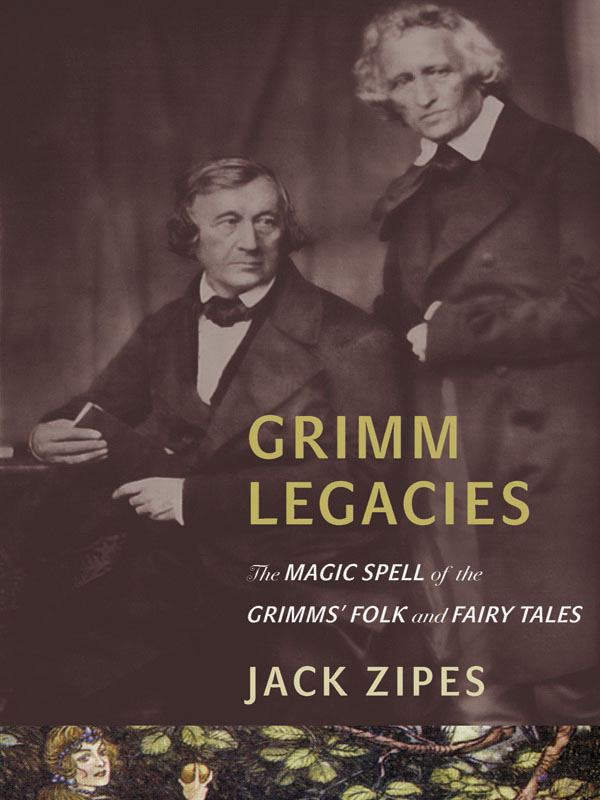

Jacket images: Photograph of Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm by Hermann Biow, 1847. Detail of illustration from The Frog Prince by Charles Folkard, orginally published in Grimms Fairy Tales, 1911.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zipes, Jack, 1937

Grimm Legacies : the Magic Spell of the Grimms Folk and Fairy Tales / Jack Zipes.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780-691160580 (hardback)

1. Grimm, Jacob, 17851863Influence. 2. Grimm, Wilhelm, 17861859Influence. 3. Fairy talesGermanyHistory and criticism. 4. TalesGermanyHistory and criticism. 5. FolkloristsGermany. I. Title.

GR166.Z57 2014

398.20943dc23

2014005508

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in 10.5/13 Minion Pro Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Heinz Rlleke

With great admiration and respect

CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

PREFACE

Legacies and Cultural Heritage

In 2012, the bicentenary year of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimms first edition of Kinder- und Hausmrchen (Children and Household Tales), published 1812 and 1815 in two volumes, numerous conferences and individual lectures in Europe and North America were held that commemorated and celebrated the achievement of the Brothers Grimm. Moreover, their tales continued to be honored in 2013 and 2014. Almost all the conferences that I attended produced new insights into the significance of the Grimms tales from different critical perspectives. Yet, from my own standpoint, it was clear to me that many scholars and critics were not fully aware of the cultural heritage of the Grimms folk and fairy tales and their impact throughout the world. Therefore, in the talks that I delivered, I concentrated on the different legacies of the Grimms tales. In my opinion, there are many legacies to consider, not just one. My goal was to test my ideas at the conferences, learn from the critical reception, and then revise my talks after a year to address the question of the legacies of the Kinder- und Hausmrchen in greater depth.

Central to my efforts was the question: Did the Grimms consciously begin collecting folk and fairy tales with the intention of bequeathing a legacy that would be cultivated in German-speaking principalities? Related to this question are others such as: What exactly is a legacy? How have the Grimms tales as legacy been received and honored in Germany up to the present? How have the tales been received as legacies in other countries and regions of the world? As I have stated, it is quite clear that there is more than one legacy. Moreover, it is also clear that the Grimms intentions were different from the reception and impact that the tales have had, not only in Germany, but also in other parts of the world. And this difference is indeed great.

To give one example: It is impossible in the twenty-first century to think of all the Walt Disney adaptations of fairy tales and their worldwide popularity without the legacy of the Brothers Grimm. In fact, it is, in part thanks to the Disney corporation, impossible to think about the dissemination of fairy tales throughout the world without taking into account the Grimms collection of tales, even though most of the Grimms stories were not strictly speaking fairy tales, nor were they intended for children. Through Disney, the Grimms name has become a household name, a trademark, and a designator in general for fairy tales that are allegedly appropriate for children. More than any author or collector of fairy tales, including Charles Perrault and Hans Christian Andersen, the Grimms are totally associated with the fairy-tale genre, and their tales, which have been translated into 150 languages, have seeped into the conscious and subconscious popular memory of people throughout the world.

Some of the ramifications of the Grimms worldwide influence have been carefully analyzed in a recent book, Grimms Tales around the Globe: The Dynamics of Their International Reception (2014) edited by Vanessa Joosen and Gillian Lathey. However, it is, of course, impossible to study the impact of the Grimms tales in the cultural heritage of all the countries in which they have had an important reception. Therefore, my present study focuses primarily on the role that the Grimms tales have played in German-speaking and English-speaking countries. My hope is that my work might pave the way for similar studies about the reception of the Grimms tales as a legacy in other countries.

Most of the essays in my book were first composed as talks that I held at various conferences and universities in 2012 and 2013. The introduction, The Vibrant Body of the Grimms Folk and Fairy Tales, Which Do Not Belong to the Grimms, discusses how the Grimms began developing the corpus of their tales at the beginning of the nineteenth century with the purpose of preserving an ancient tradition of storytelling. The Brothers were among the first scholars to recall and establish the historical tradition of authentic folk tales that stemmed from oral storytelling. In the course of their research from 1806 until their deaths, Wilhelm in 1859, and Jacob in 1863, they published seven large editions and ten small editions of folk and fairy tales along with separate volumes of notes that were constantly changed and edited. These are the books that form the body of their work on folk and fairy tales, but it is a live and vibrant body that consists of other books of legends and tales that they collected, edited, and published. In addition, one must take into consideration the 150 or more translations and the Grimms manuscripts such as the lenberg manuscript of 1810 and their posthumous papers. What then, I ask, is the corpus that they left behind them? How are we to appraise the neverending and seemingly eternal reproduction of their tales?

In (3) that the tales were German (which they arent). The great success of Taylors books with illustrations by the famous caricaturist, George Cruikshank, stimulated the Brothers, especially Wilhelm, to change the format of their tales so that they might find a greater resonance among young readers primarily from middle-class families in German-speaking principalities.

, Hyping the Grimms Fairy Tales, explores Taylors influence in greater depth to examine how, without realizing it, the Brothers began embellishing and marketing their tales to seek a greater reading public. There was an overt change in policy that was initiated in 1825, when they decided to publish their Small Edition of fifty tales with illustrations by their brother Ludwig Grimm. It was not a question of money and profit, but the Grimms created more hyperbolic paratexts to their editions with the hope that German folk culture would gain the respect that it deserved. At the same time, they also maintained their scholarly philological approach. However, in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries this marketing strategy also led to a trivialization if not banalization of the tales. So in this chapter, I discuss the ramifications of hyping the Grimms tales in todays hyperglobalized cultures.

Next page