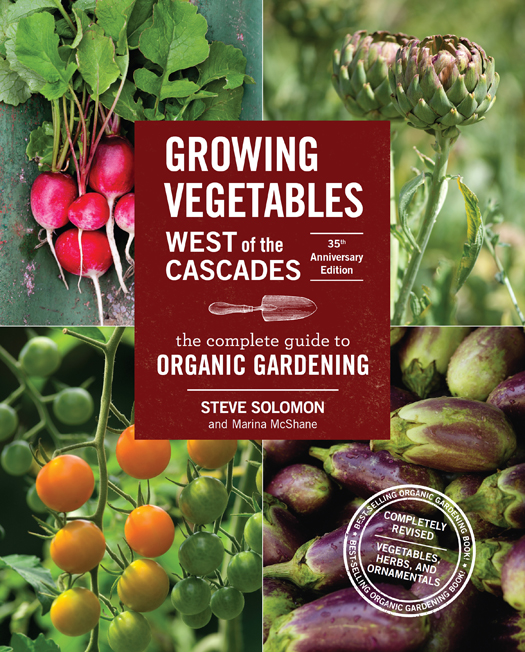

Copyright 2015 by Steve Solomon and Marina McShane

Illustrations copyright 2000 by Muriel Brown

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by Sasquatch Books

Editors: Gary Luke and Christy Cox

Production editor: Emma Reh

Illustrations: Muriel Brown

Cover design: Anna Goldstein

Cover photos: iStock.com/ Innershadows/ Radishes

Alloy Photography/ Veer/ Tomatoes

Zidi/ Veer/ Artichokes

Collage Photography/ Veer/ Eggplants

Interior design: Rebecca Shapiro

Interior composition: Scott Taylor

Copyeditor: Carrie Wicks

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-57061-972-4

eBook ISBN: 978-1-57061-973-1

Sasquatch Books

1904 Third Avenue, Suite 710

Seattle, WA 98101

(206) 467-4300

www.sasquatchbooks.com

v3.1

CHAPTER TEN: Ornamentals and Herbs

by Marina McShane

Introduction

IntroductionThe cheapest experience you can get comes secondhand if youll only buy it.

S IDNEY S OLOMON, MY FATHER, IN PRIVATE CONVERSATION

IN YOUR HANDS is a food gardening guide for the Cascadia bioregion. Most people call it the maritime Northwest.

Cascadia needs its own food gardening book. West of the mountains, summer days are rarely hot except for a few days during most summers, when they get really hot; rarely do summer nights feel warm enough for short-sleeved shirts. Heat-demanding vegetable varieties that perform excellently in the Midwest grow poorly in Cascadia. Cascadian gardens can provide vegetables during the winter when soils east of the Rocky Mountains are frozen solid several feet deep; eastern books say nothing about this possibility. Cascadia has a perverse rainfall pattern; lots of moisture in winter when crops dont need it, but little or none in summer when they do. Heavy winter rains combined with a unique geology have leached Cascadian soils into a pattern of infertility far different than the soils of the eastern United States. The East contends with different pests; traditional eastern techniques that evade those difficulties do not apply to Cascadia.

Had the indigenous Cascadians been food gardeners, then the first Anglo-Americans arriving in the Oregon Territory might have learned regionally appropriate agriculture from them. But the tribes along the West Coast did not grow food. So the invaders farmed and gardened as though they were still in Ohio (where the largest fraction of them came from). As I learned more about Cascadian soils, I came to think the local tribes intelligently avoided food gardening. I also strongly suspect, without evidence, that the first Cascadians knew other Native Americans raised crops, and probably tried it themselves in natural meadows. And failed.

When I arrived in the late 1970s, Cascadia resembled a Third World country exporting wood products and farm crops. Like other poor countries, Cascadia imported technology. We used gardening books published in New York City or Emmaus, Pennsylvania, and we bought seeds from mail-order catalogs east of the Rockies and from national picture-packet distributors racks that offered varieties not suited to Cascadia. I settled in Oregon one year before the publication of Binda Colebrooks Winter Gardening in the Maritime Northwest. Bindas book opened my eyes to this possibility. Thanks to Binda, I started Territorial Seed Company because seeds for varieties crucial to winter gardening were difficult to obtain.

These days many Cascadian gardeners take advantage of their climates possibilities. Reputable regional garden/homestead seed businesses and seedling growers now supply appropriate varieties. I feel proud to have helped this transformation along. I consider Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades to be a valuable regional resource that I am responsible for, so I have kept this book in print by steadily improving it as I learned more. The last major upgrades were made for the fifth edition, published over 15 years ago. This, the seventh, has been broadly improved by 15 more years of growing experience and the great deal Ive learned about soil fertility in that time.

Marina McShane, an old and dear friend who lives near Eugene, Oregon, and has been gardening nearly as many years as I have, helped me write this edition because in 1994 I moved to Nelson, British Columbia, and soon thereafter was led to Tasmania, the smallest and least-known state of Australia. Tassie is a remote, uncrowded temperate South Pacific island, slightly smaller than western Oregon, with a noticeably lower population density. I feel blessed to live here. Tassie life these days is a lot like Oregon was when I first settled there. Tasmania is a hardscrabble place of forests, fisheries, and sheep; of people mostly concerned about family; of narrow, twisty roads and slightly untidy homesteads with chickens, vegetable gardens, and sometimes a house cow. Tasmanians who are after material wealth move to the mainland.

Locals consider the part of Tasmania I live in a banana belt, much like Elkton, Oregon, where I used to live. Where I garden now has a climate like youd find near the Rogue River, 5 miles inland from Gold Beach, Oregon, so I have not forgotten how to take full advantage of Cascadias climate. In fact, living in this gentle district has shown me winter gardening possibilities that apply to coastal Northern California. What I have lost touch with are the newest pest control products and some new vegetable varieties because Australia Quarantine makes it awkward to fully evaluate them. In addition to contributing generally, Marina has investigated and written up those specific areas.

Why I Grow Most of My Own Food

M arina and I have long been homesteaders. Homesteading means producing products or services from your own property that earn income or that are personal survival necessities, like food or firewood. I encourage this lifestyle because when people create any part of their necessities, they develop confidence. Theyre less concerned with pleasing the authority paying their salary; theyre less dependent on a government that cant be influenced and often works toward harmful ends. I think life would be better for everyone if more people would produce their own necessities. Many independence-minded Cascadians agree with me. Thats why Ive sold so many books these past 35 years and why Territorial Seed Company did surprisingly well.

Independence mindedness greatly increases when a person enjoys a high degree of physical well-being, but these days the majority of North Americans are trapped in a dwindling spiral, starting with poor nutrition leading to poor health, leading to dependency on medicines that further lower overall health. The way out is not found by seeking a smarter doctor. The way out requires (1) overcoming unhealthy eating habits and switching to nutrient-dense whole foods while (2) eliminating otherwise decent foods that happen to be inappropriate for your bodys genetic makeup or foods it reacts badly to. In my opinion thats all it takes to keep most people healthy, make them energetic and optimistic, and make them live longer. For those who havent degenerated too far, eating right heals diseases caused by years of wrong feeding.