THE OXFORD SHAKESPEARE

General Editor Stanley Wells

THE OXFORD SHAKESPEARE

Richard II

EDITED BY ANTHONY B. DAWSON AND PAUL YACHNIN

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Anthony B. Dawson and Paul Yachnin 2011

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

Typeset by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

MPG Books Group, Bodmin and Kings Lynn

ISBN 9780198186427 (hardback)

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

OXFORD WORLDS CLASSICS

For over 100 years Oxford Worlds Classics have brought readers closer to the worlds great literature. Now with over 700 titlesfrom the 4,000-year-old myths of Mesopotamia to the twentieth centurys greatest novelsthe series makes available lesser-known as well as celebrated writing.

The pocket-sized hardbacks of the early years contained introductions by Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Graham Greene, and other literary figures which enriched the experience of reading. Today the series is recognized for its fine scholarship and reliability in texts that span world literature, drama and poetry, religion, philosophy, and politics. Each edition includes perceptive commentary and essential background information to meet the changing needs of readers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our edition, the last of the Oxford series, has been a long while gestating and during that time we have incurred a number of debts. To previous editors of the play, especially Peter Ure (Arden 2), Stanley Wells (Penguin), Andrew Gurr (Cambridge), John Jowett et al. (Complete Oxford), and Charles Forker (Arden 3), we owe dozens of insights both textual and semantic. Several graduate student research assistants have contributed significantly and cheerfully to the shaping of this edition. Amy Scott provided assistance with bibliography early in the project and excellent service on a number of matters, especially the images, toward the end. Karen Oberer worked through the text with Paul Yachnin before he and Anthony Dawson analysed and shaped it again; the earlier process is vestigial but foundational. David Anderson provided assistance with the commentary, again at an early stage, while Andrew Brown and Katie Davison helped with indexing and proofs near the end. Colleagues have also graciously lent their help. Of these we would like to thank especially Patsy Badir, Bradin Cormack, David George, Gordon McMullan, Michael Neill, Patricia Parker, Steve Partridge, and Carol Rutter. We thank Kate Rumbold and Christie Carson for timely advice about sourcing of images. The staff of the Folger Shakespeare Library, especially Georgianna Ziegler, have been hugely supportive; the Folger collection has been an indispensable resource. The Shakespeare Association of America sponsored a research seminar on Richard II, led by Paul Yachnin, whose members helped deepen our understanding of the play. Steven Mullaney was a member of that seminar; his thinking about the theatre and the play has been of considerable value. We are pleased to acknowledge the careful and creative contributions of our copy-editor, Christine Buckley, whose judicious attention to detail rescued us from error on many occasions. More than anything, it is a pleasure to thank the General Editor. Many Oxford editors have said it before us; it is true: Stanley Wells is a model of patience, deep learning, and great intellectual generosity. He has no part in any of the faults of this edition, but a substantial share in anything in it that is sound and insightful. Finally, we would like to thank each otherthis is not the first time that we have worked together collaboratively, and we are pleased that the spirit of cooperation and friendly debate established in our earlier work together has remained as vital as in the past.

CONTENTS

(with permission of the National Portrait Gallery)

(This item is reproduced by permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California)

(National Gallery, London, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library)

(University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections)

(with permission of Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey)

(with permission of the National Portrait Gallery)

(Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

(Joe Cocks Studio Collection at Shakespeare Birthplace Trust)

(Magnum Photos / Martine Franck)

(Rex Features)

(Laurence Burns / ArenaPAL)

(with permission of Donald Cooper / Photostage)

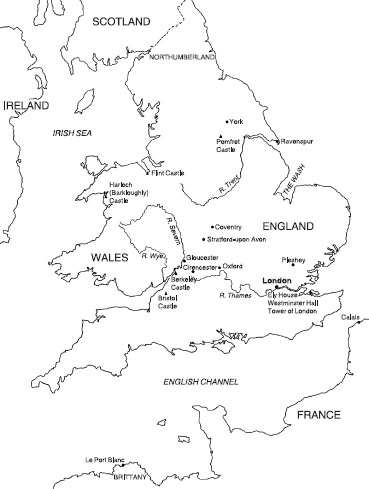

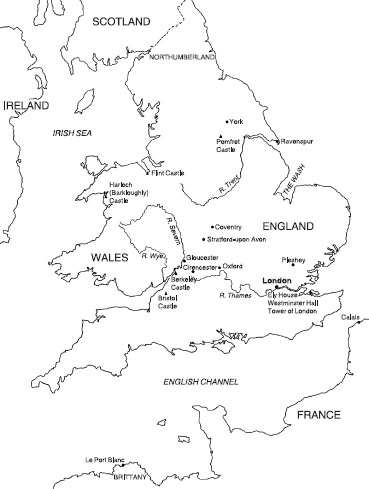

1. Map of England showing the Key locations mentioned in the play.

Richard II occupies an important place in the Shakespeare canon. Written in 1595, at a point when Shakespeare was finding his full stride as a poet and dramatist, the play marks a transition from the earlier history plays (the first tetralogy comprising the three parts of Henry VI and Richard III) in which the terrible mechanisms of civil war and naked power dominate the scene. Here a new note is audible, a more nuanced representation of the political conflicts of the English past in which character and politics are so deeply intertwined as to be inextricable. The language too is suppler and more richly elaborated. Overall, there is a sense of emerging mastery, as there is too in the other plays he completed in that very productive year, A Midsummer Nights Dream and Romeo and Juliet. In Dream he takes the comic genre in which he had worked in several earlier plays to new heights of complexity while Romeo, with its subtle blend of chance and inevitability, does something similar for tragedy (his only previous tragedy had been the bloody and savage revenge play,