. She has also written two works of autobiography,

. The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship and an NEA fellowship, Silko lives in Tucson, Arizona, on the boundary of Saguaro National Park West.

STORYTELLER

LESLIE MARMON SILKO

PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in the United States of America by Arcade Publishing, Inc. p. cm. cm.

ISBN: 978-1-101-62191-2 1. Indians of North AmericaFiction. I. Title. PS3569.I44S55 2012 813.54dc23 2012023724 Printed in the United States of America Set in Fournier Designed by Ginger Legato Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

This book is dedicated to the storytellers as far back as memory goes and

to the telling which continues and through which they all live and we with them.ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

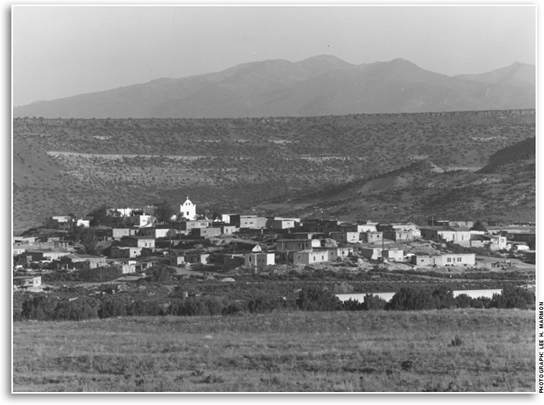

Nearly all of the photographs were taken by my father, Lee Marmon. He set out in 1949 to record the beauty of the elders and the beauty of the land lest they be forgotten. I want to thank him for his lifetimes work as well as to thank him for finding the prints I needed for this new version of

Storyteller. Many thanks to his wife, Kathy, who sent the digital images.

Many thanks to Mike Kelly at the University of New Mexicos Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, who helped us obtain the images of the Lee Marmon prints in the New Mexico Digital Collections. The Lee Marmon collection can be viewed at http://econtent.unm.edu.

INTRODUCTION

All human languages have words and tones of voice we use when we want to impart information. If you think about it, nearly everything of consequence that we tell one another involves narration or story. When we explain ourselves or our reasoning in a situation, when we describe what we remember of an experience, we organize the experience into a narrative structure to communicate the information. The narrative may begin anywhereat the conclusion of the incident with the result, then backtracking to the actions that led to the results.

Or one may start at the beginning and proceed in a linear manner, step by step leading to the action and finally the conclusion. Often there are stories about other stories and differing versions of the same events. The human capacity for language and storytelling go hand in hand. Neither precedes the other; rather, the urge to share our experience, to tell our stories to another human is so strong that humans invented languagessign languages and spoken languages but also dance, music, and painting in order to communicate the full range of our experiences. Sign languages are highly sophisticated and involve body language, which may reveal far more than the spoken word. Sign languages must have served our ancient ancestors well on the African plains when they were stalking game and any sound would stampede the prey; sign language also served humans when danger threatened, and silence was essential.

Help! might have been one of the first words in human language, along with run! Or hide! But once the danger had passed, the urge to tell and the need to know what had happened would have been paramount. This exchange of information through stories about what had just happened was a primary factor in the survival of human species in a world in which nearly all creatures were either bigger, stronger, or faster than human beings. So I imagine that at first humans exchanged stories to acquire knowledge as a survival strategy, to learn to anticipate the many threats and dangers in their world. Considerable details and vivid descriptions were essential to the telling; the most important actions in a story might be repeated to make sure the listeners remembered what to do to survive in a similar situation. I like to imagine that the listeners took solace but also pleasure in hearing these stories told by survivorsamazing stories with happy endings. These stories gave them the heart to face danger with the hope that if they did exactly what the survivor had done then they too might survive.

So they paid close attention to the survivors story, and thus stories rich in detail and description became the most pleasurable because they gave the listeners the most information. The association of knowledge with power begins here. Storytelling also gave expression to fears and dreams and to faith and belief. Religious ceremonies came out of certain sacred stories that described the relationship between humans and the spirit world or gods. Storytelling among the family and clan members served as a group rehearsal of survival strategies that had worked for the Pueblo people for thousands of years. This was the case among the Pueblo people of the southwest and at Laguna Pueblo, where I am from.

The entire culture, all the knowledge, experience, and beliefs, were kept in the human memory of the Pueblo people in the form of narratives that were told and retold from generation to generation. The people perceived themselves in the world as part of an ancient continuous story composed of innumerable bundles of other stories. The impulse of the old-time Pueblo people was to leave nothing outthey were not prudish about subject matter because valuable experience and knowledge are found in all levels of human activity. As I wrote in my essay on story and landscape: Accounts of the appearance of the first Europeans in Pueblo country or the tragic encounters between Pueblo people and Apache raiders were no more and no less important than stories about the biggest mule deer ever taken or adulterous couples surprised in cornfields and chicken coops. Whatever happened, the Pueblo people instinctively sorted events and details into a loose narrative structure. Everything became story.

PENGUIN BOOKS STORYTELLER Leslie Marmon Silko is the author of the novels Ceremony, Almanac of the Dead, and Gardens in the Dunes. She has also written two works of autobiography, Sacred Water and The Turquoise Ledge; a collection of essays, Yellow Woman and a Beauty of theSpirit; and a book of verse, Laguna Woman. The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship and an NEA fellowship, Silko lives in Tucson, Arizona, on the boundary of Saguaro National Park West.

PENGUIN BOOKS STORYTELLER Leslie Marmon Silko is the author of the novels Ceremony, Almanac of the Dead, and Gardens in the Dunes. She has also written two works of autobiography, Sacred Water and The Turquoise Ledge; a collection of essays, Yellow Woman and a Beauty of theSpirit; and a book of verse, Laguna Woman. The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship and an NEA fellowship, Silko lives in Tucson, Arizona, on the boundary of Saguaro National Park West.  Laguna Pueblo

Laguna Pueblo  PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3