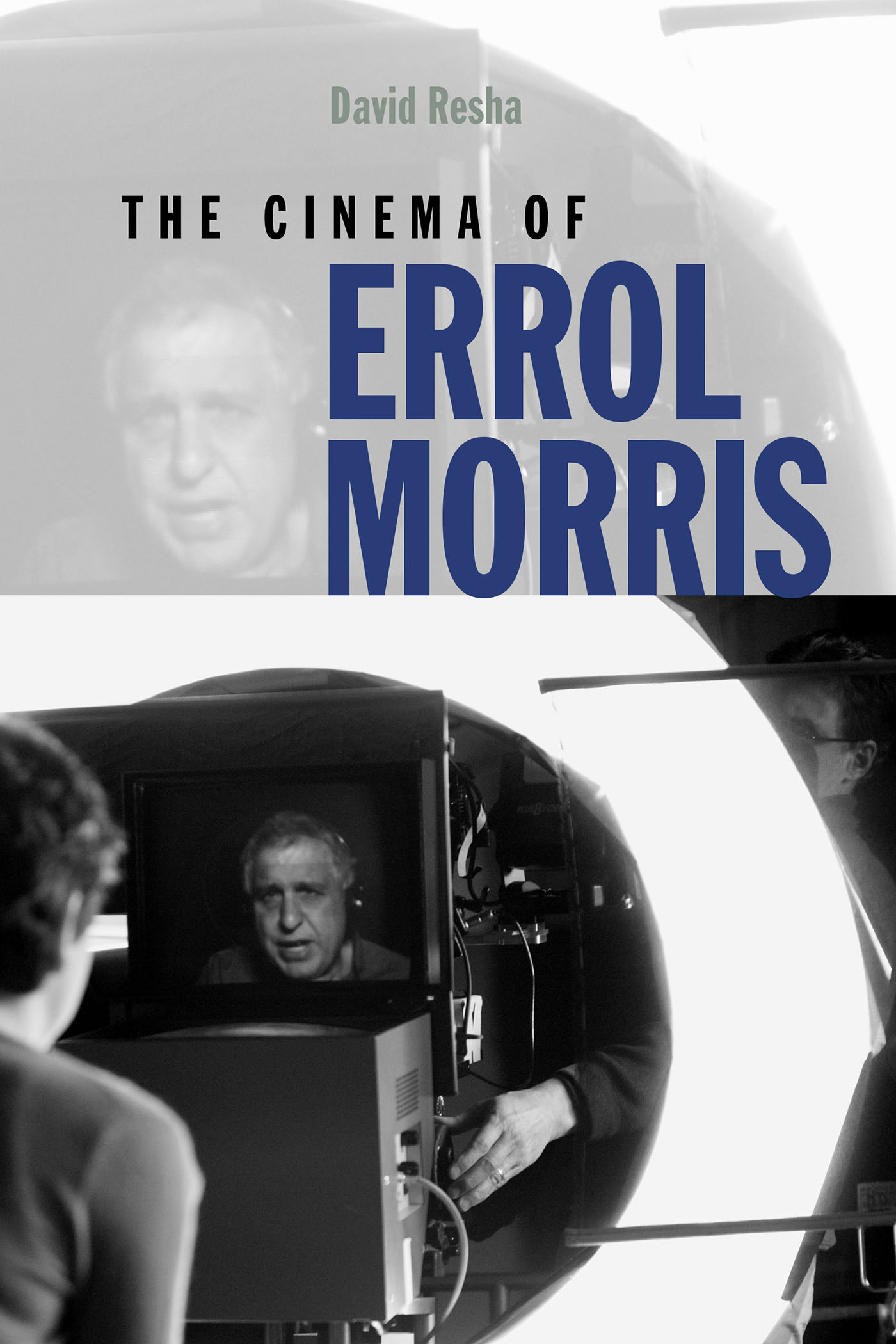

THE CINEMA OF Errol Morris

David Resha

THE CINEMA OF ERROL MORRIS

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS MIDDLETOWN, CONNECTICUT

Wesleyan University Press

Middletown CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2015 David Resha

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by Eric M. Brooks

Typeset in Quadraat by Passumpsic Publishing

Wesleyan University Press is a member of the Green Press Initiative. The paper used in this book meets their minimum requirement for recycled paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Resha, David.

The cinema of Errol Morris / David Resha.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780819575333 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780819575340 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780819575357 (ebook)

1. Morris, ErrolCriticism and interpretation. I. Title.

PN1998.3.M684R472015

791.430233092dc232014037174

5 4 3 2 1

Cover illustration: Errol Morris interviewing Sabrina Harman using the Interrotron. Photo: Nubar Alexanian

CONTENTS

PREFACE

When I first watched a dusty VHS copy of The Thin Blue Line, it was unlike any documentary I had seen before, and I was deeply moved by the experience. The film was funny, sad, and enigmatic. Sequences such as the slow-motion flying milkshake and Emily Millers Boston Blackie fantasies stuck with me. I frequently invited friends to watch it with me, and I enjoyed it more with every viewing. But I could not get to the bottom of it. It was not a movie that merely taught or preached. It felt as if it was trying to get at something difficult, something deepand was struggling with that investigation.

It was not easy to see Errol Morriss documentaries at the time. I once took a train down to a small, backroom screening of Gates of Heaven in a New York City bar. Weeks later, I bought a beat-up, dubbed VHS copy of Vernon, Florida on eBay. As I watched more of Morriss films, I started to notice continuities in his approach to his subjects. Morriss interviews did not always stick to the issue. The films gave people the freedom to talkabout their past, their fears, and their dreams. And this seemed to interest Morris more than anything else, as the films would follow these tangents to see where they led.

Errol Morriss films were willing to tackle difficult philosophical problems without relying on ambiguity or obfuscation as an empty posture. Morris himself seemed to be both fascinated and terrified by the world, and the complexities of film style and structure in his films raised more questions than they answered. His films, as with all great films, reward multiple, careful viewings. If nothing else, I hope this book encourages people to not just watch Errol Morriss movies but also watch them closely.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe a great deal to my professors, colleagues, friends, and family who helped me complete this book. I would like to thank Vance Kepley for his invaluable encouragement and guidance. Jeff Smith, JJ Murphy, Kelley Conway, and Julie Dacci provided perceptive feedback. I am grateful for all of the superb thinkers and teachers in the Communication Arts department at the University of WisconsinMadison, including Ben Singer, Bill Brown, and Lea Jacobs. I am also indebted to David Bordwell, whose scholarship, generosity, and kindness will always be an inspiration for me.

Thanks to my colleagues and friends from my cherished days in Madison. Brad Schauer, Pearl Latteier, Mark Minett, Heather Heckman, John Powers, Casey Coleman, Ethan de Seife, Kaitlin Fyfe, and Maureen Larkin all politely tolerated my love for documentary films and enthusiastically enabled my love for beer. Happy hour with Colin Burnett was consistently enlightening and whiskey tastings with Jake Smith helped clear my mind. I am particularly grateful for Jessica Newmans intelligence, humor, and compassion. This book would not have been possible without her. My parents and my brother Joe have always been loving and supportive, and I owe them a great deal.

Birmingham-Southern College has generously supported the process of writing this book. Mary-Kate Lizotte, Mark Schantz, and many others have generously assisted me throughout this time. Wesleyan University Press and Parker Smathers were very helpful with this process as well. In addition, many of Errol Morriss collaborators, including Jed Alger, Robert Fernandez, and Brad Fuller, kindly answered my questions.

Finally, I would like to thank Errol Morris. It has been a pleasure to watch and write about Mr. Morriss intelligent, challenging, and poignant films.

THE CINEMA OF Errol Morris

Introduction

THE EMERGENCE OF DIRECT CINEMA in the sixties marked an exciting new development in nonfiction filmmaking. At the time, large, heavy filmmaking equipment made it difficult for filmmakers to capture the unpredictable events. Conventional documentaries, typified by newsreels and educational films, would often use devices such as voice-over narration, interviews, and staged sequences to help communicate information about the world that was difficult or impossible to film.

Robert Drew formed Drew Associates in 1960 to produce observational films that would be markedly different from this standard approach to nonfiction filmmaking. In particular, Drew wanted to move away from what he called lecture films: My theoretical view developed that we could capture real people, real stories, in real life, [and] edit them in such a way that the stories would tell themselves without the aid of a lot of narration. Drew Associates films such as Primary (1960), The Chair (1962), and Salesman (1968) brought together new technological advances like lightweight, portable 16 mm cameras and synchronized sound with rigid limitations on the filmmakers intervention in the filmed events, such as avoiding reenactments and formal interviews.

While some critics were enthusiastic about these observational films, others argued that these filmmakers were naive to connect their less intrusive style to a more objective representation of reality. Reflexive documentaries often challenge the conventions of realism, inviting the viewer to question the idea that certain documentary techniques provide unproblematic access to the world.

Filmmakers produced reflexive documentaries decades before the emergence of Direct Cinema, for example, Dziga Vertovs Man with a Movie Camera (1929). There were increasing calls for a deliberate movement of reflexive nonfiction work by the 1970s. In a 1977 article, Jay Ruby argues, I am convinced that filmmakers along with anthropologists have the ethical, political, aesthetic, and scientific obligations to be reflexive and self-critical about their work. Reflexive documentaries did attain some degree of prominence in the 1970s and 80s. Films such as No Lies (1973), Daughter Rite (1978), and Far from Poland (1984) questioned the status and limitations of the documentary form.

By the late 1980s, when Errol Morris emerged to prominence, reflexivity was a prevalent critical framework for understanding innovative and challenging documentaries. Critics and theorists who championed the idea of reflexive documentaries embraced Morriss films and, in particular, his 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line. Morriss use of highly stylized visuals and complex narratives, as well as his interest in exploring epistemological problems in his films, seemed to fit the emerging definition of the reflexive documentary.

There are central features in Errol Morriss work, however, that are lost in the reflexive characterizations of his films. Morriss films are not merely occasions to reflect on the problems of documentary representation. This characterization of his documentaries oversimplifies what are complex, emotionally engaging, and dynamic examinations of the world, examinations that are primarily interested in exploring the inner lives of its subjects.

Next page