Copyright 1934, 1941 by The Modern Library, Inc.

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio or television review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Preface

to the

First Edition

I am writing this preface to the first edition so that in the event that this book is issued in a second edition I will be able to write a preface to the second edition, explaining what I said in the preface to the first edition and adding a few remarks about what I have been doing in the meantime, and so on.

In the event that the book reaches a third edition, it is my plan to write a preface to the third edition, covering all that I said in the prefaces to the first and second editions, and it is my plan to go on writing prefaces for new editions of this book until I die. After that I hope there will be children and grandchildren to keep up the good work.

In this early preface, when I have no idea how many copies of the book are going to be sold, the only thing I can do is talk about how I came to write these stories.

Years ago when I was getting a thorough grammar-school education in my home town I found out that stories were something very odd that some sort of men had been turning out (for some odd reason) for hundreds of years, and that there were rules governing the writing of stories.

I immediately began to study all the classic rules, including Ring Lardners, and in the end I discovered that the rules were wrong.

The trouble was, they had been leaving me out, and as far as I could tell I was the most important element in the matter, so I made some new rules.

I wrote rule Number One when I was eleven and had just been sent home from the fourth grade for having talked out of turn and meant it.

Do not pay any attention to the rules other people make, I wrote. They make them for their own protection, and to hell with them. (I was pretty sore that day.)

Several months later I discovered rule Number Two, which caused a sensation. At any rate, it was a sensation with me. This rule was: Forget Edgar Allan Poe and O. Henry and write the kind of stories you feel like writing. Forget everybody who ever wrote anything.

Since that time I have added four other rules and I have found this number to be enough. Sometimes I do not have to bother about rules at all, and I just sit down and write. Now and then I stand and write.

My third rule was: Learn to typewrite, so you can turn out stories as fast as Zane Grey.

It is one of my best rules.

But rules without a system are, as every good writer will tell you, utterly inadequate. You can leave out utterly and the sentence will mean the same thing, but it is always nicer to throw in an utterly whenever possible. All successful writers believe that one word by itself hasnt enough meaning and that it is best to emphasize the meaning of one word with the help of another. Some writers will go so far as to help an innocent word with as many as four and five other words, and at times they will kill an innocent word by charity and it will take years and years for some ignorant writer who doesnt know adjectives at all to resurrect the word that was killed by kindness.

Anyway, these stories are the result of a method of composition.

I call it the Festival or Fascist method of composition, and it works this way:

Someone who isnt a writer begins to want to be a writer and he keeps on wanting to be one for ten years, and by that time he has convinced all his relatives and friends and even himself that he is a writer, but he hasnt written a thing and he is no longer a boy, so he is getting worried. All he needs now is a system. Some authorities claim there are as many as fifteen systems, but actually there are only two: (1) you can decide to write like Anatole France or Alexandre Dumas or somebody else, or (2) you can decide to forget that you are a writer at all and you can decide to sit down at your typewriter and put words on paper, one at a time, in the best fashion you know howwhich brings me to the matter of style.

The matter of style is one that always excites controversy, but to me it is as simple as A B C, if not simpler.

A writer can have, ultimately, one of two styles: he can write in a manner that implies that death is inevitable, or he can write in a manner that implies that death is not inevitable. Every style ever employed by a writer has been influenced by one or another of these attitudes toward death.

If you write as if you believe that ultimately you and everyone else alive will be dead, there is a chance that you will write in a pretty earnest style. Otherwise you are apt to be either pompous or soft. On the other hand, in order not to be a fool, you must believe that as much as death is inevitable life is inevitable. That is, the earth is inevitable, and people and other living things on it are inevitable, but that no man can remain on the earth very long. You do not have to be melodramatically tragic about this. As a matter of fact, you can be as amusing as you like about it. It is really one of the basically humorous things, and it has all sorts of possibilities for laughter. If you will remember that living people are as good as dead, you will be able to perceive much that is very funny in their conduct that you perhaps might never have thought of perceiving if you did not believe that they were as good as dead.

The most solid advice, though, for a writer is this, I think: Try to learn to breathe deeply, really to taste food when you eat, and when you sleep, really to sleep. Try as much as possible to be wholly alive, with all your might, and when you laugh, laugh like hell, and when you get angry, get good and angry. Try to be alive. You will be dead soon enough.

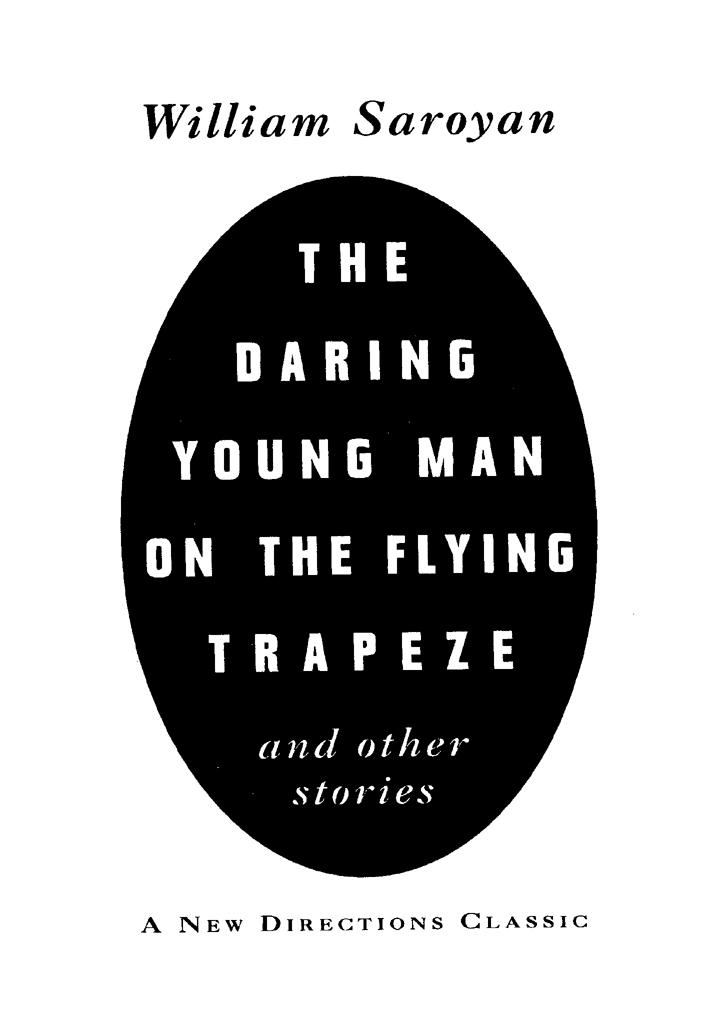

The

Daring Young Man

on the

Flying Trapeze

I. SLEEP

Horizontally wakeful amid universal widths, practising laughter and mirth, satire, the end of all, of Rome and yes of Babylon, clenched teeth, remembrance, much warmth volcanic, the streets of Paris, the plains of Jericho, much gliding as of reptile in abstraction, a gallery of watercolors, the sea and the fish with eyes, symphony, a table in the corner of the Eiffel Tower, jazz at the opera house, alarm clock and the tap-dancing of doom, conversation with a tree, the river Nile, Cadillac coupe to Kansas, the roar of Dostoyevsky, and the dark sun.