Table of Contents

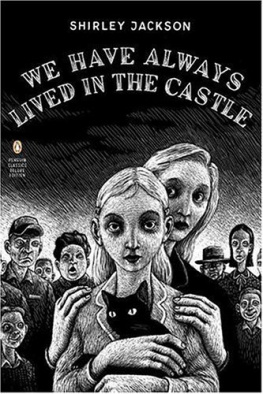

WE HAVE ALWAYS LIVED IN THE CASTLE

SHIRLEY JACKSON was born in San Francisco in 1916. She first received wide critical acclaim for her short story The Lottery, which was published in 1949. Her novelswhich include The Sundial, The Birds Nest, Hangsaman, The Road through the Wall, and The Haunting of Hill House (Penguin), in addition to We Have Always Lived in the Castle (Penguin)are characterized by her use of realistic settings for tales that often involve elements of horror and the occult. Raising Demons and Life among the Savages (Penguin) are her two works of nonfiction. She died in 1965. Come Along With Me (Penguin) is a collection of stories, lectures, and part of the novel she was working on when she died in 1965.

JONATHAN LETHEM is the author of Motherless Brooklyn, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction, as well as the novels The Fortress of Solitude; Gun, with Occasional Music; As She Climbed Across the Table; Girl in Landscape ; and Amnesia Moon. He has also published stories (Men and Cartoons) and essays (The Disappointment Artist).

Introduction

Life in Shirley Jacksons (Out)Castle

Ten and twenty years ago I used to play a minor parlor trick; I wonder if it would still work. When asked my favorite writer, Id say Shirley Jackson, counting on most questioners to say theyd never heard of her. At that Id reply, with as much smugness as I could muster: Youve read her. When my interlocutor expressed skepticism, Id describe The Lotterystill the most widely anthologized American short story of all time, Id bet, and certainly the most controversial, and censored, story ever to debut in The New Yorkercounting seconds to the inevitable widening of my victims eyes: theyd not only read it, they could never forget it. Id then happily take credit as a mind reader, though the trick was too easy by far. I dont think it ever failed.

Jackson is one of American fictions impossible presences, too material to be called a phantom in literatures house, too in-print to be rediscovered, yet hidden in plain sight. Shes both perpetually underrated and persistently mischaracterized as a writer of upscale horror, when in truth a slim minority of her works had any element of the supernatural (Henry James wrote more ghost stories). While celebrated by reviewers throughout her career, she wasnt welcomed into any canon or school; shes been no major critics fetish. Sterling in her craft, Jackson is prized by the writers who read her, yet it would be self-congratulatory to claim her as a writers writer. Rather, Shirley Jackson has thrived, at publication and since, as a readers writer. Her most famous worksThe Lottery and The Haunting of Hill Houseare more famous than her name, and have sunk into cultural memory as timeless artifacts, seeming older than they are, with the resonance of myth or archetype. The same aura of folkloric familiarity attaches to less-celebrated writing: the stories Charles and One Ordinary Day, With Peanuts (youve read one of these two tales, though you may not know it), and her last novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle.

Though she teased at explanations of sorcery in both her life and in her art (an early dust-flap biography called her a practicing amateur witch, and she seems never to have shaken the effects of this debatable publicity strategy), Jacksons great subject was precisely the opposite of paranormality. The relentless, undeniable core of her writingher six completed novels and the twenty-odd fiercest of her storiesconveys a vast intimacy with everyday evil, with the pathological undertones of prosaic human configurations: a village, a family, a self. She disinterred the wickedness in normality, cataloguing the ways conformity and repression tip into psychosis, persecution, and paranoia, into cruelty and its masochistic, injury-cherishing twin. Like Alfred Hitchcock and Patricia Highsmith, Jacksons keynotes were complicity and denial, and the strange fluidity of guilt as it passes from one person to another. Her work provides an encyclopedia of such states, and has the capacity to instill a sensation of collusion in her readers, whether they like it or not. This reached a pitch, of course, in outraged reactions to The Lottery: the bags of hate mail denouncing the story as nauseating, perverted, and vicious, the cancelled subscriptions, the warnings to Jackson never to visit Canada.

Having announced her themeJacksons first novel, The Road Through the Wall, finished just prior to The Lottery, is a coruscating expose of suburban wickednessJackson devoted herself to burrowing deeper inside the feelings that appalled her, to exploring them from within. Jacksons biographer, Judy Oppen-heimer, tells how in the last part of Jacksons too-brief life the author succumbed almost entirely to crippling doubt and fear, and in particular to a squalid, unreasonable agoraphobiaa sort of horrible parody of the full-time homemakers role shed assumed both in her life and in her cheery, proto-Erma Bombeckian best sellers Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons. However painful her final decade, though, her work enlarges as it descends, from the sly authority of The Lottery, into moral ambiguity, emotional unease, and self-examination. The novels and stories grow steadily more eccentric and subjective, and funnier, climaxing in We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which I think is her masterpiece.

The Lottery and Castle are intertwined by the motif of small-town New England persecution; the town, in both instances, is pretty well recognizable as North Bennington, Vermont. Jackson lived there most of her adult life, the faculty wife of literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, who taught at nearby Bennington College. Jackson was in many senses already two people when she arrived in Vermont. The first was a fearful ugly duckling, cowed by the severity of her upbringing by a suburban mother obsessed with propriety. This half of Jackson was a character she brought brilliantly to life in her stories and novels from the beginning: the shy girl, whose identity slips all too easily from its foundations. The other half of Jackson was the expulsive iconoclast, brought out of her shell by her marriage to Hymanhimself a garrulous egoist, typical of his generation of Jewish50s New York intellectualsand by the visceral shock of mothering a quartet of noisy, demanding babies. This was the Shirley Jackson that the town feared, resented and, depending on whose version you believe, occasionally persecuted. For it was her fate, as an eccentric newcomer in a staid, insular village, to absorb the reflexive anti-Semitism and anti-intellectualism felt by the townspeople toward the college. The hostility of the villagers helped shape Jacksons art, a process that eventually redoubled, so that the latter fed the former. After the success-de-scandal of The Lottery a legend arose in town, almost certainly false, that Jackson had been pelted with stones by schoolchildren one day, then gone home and written the story. (Full disclosure: I lived in North Bennington for a few years in the early eighties, and some of the local figures Jackson had contended with twenty years before were still hanging around the town square where the legendary lottery took place.)

In Castle, Jackson revisits persecution with force and a certain amount of glee, decanting it from the realm of objective social critique into personal fable. In a strategy shed been perfecting since the very start of her writing, that of splitting her aspects among several characters in the same story, Jackson delegates the halves of her psyche into two odd, damaged sisters: the older Constance Blackwood, hypersensitive and afraid, unable to leave the house; and the younger Merricat Blackwood, a willful demon prankster attuned to nature, to the rhythm of the seasons, and to death, and the clear culprit in the unsolved crime of having poisoned all the remaining members of the Blackwood family (apart from Uncle Julian).