For Sarah and Sam

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

PREFACE

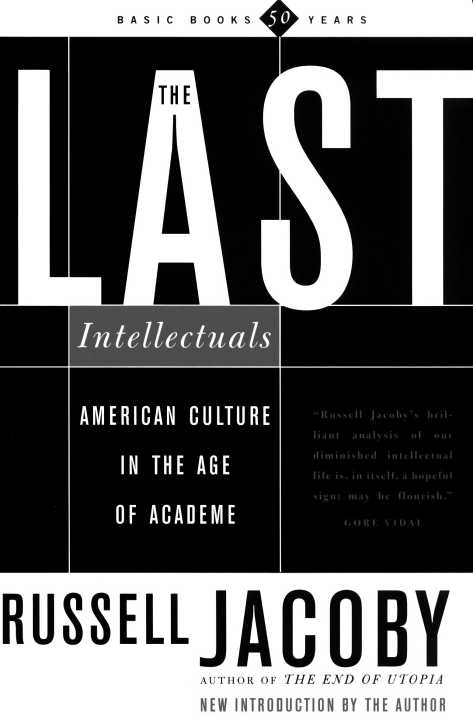

"WHERE ARE our intellectuals?" In his 1921 book, America and the Young Intellectual, Harold Stearns (1891-1943), a chronicler of his generation, asked this question.' He found them fleeing to Europe, an act he supported and soon followed, joining what became the most celebrated of American intellectual groupings, the lost generation.

Stearns's question may speak to the present, but his answer does not. He believed that the hostility of a commercial civilization to youth in general, and to intellectuals in particular, drove young writers to Europe. This does not capture the current situation. Youth is lionized; intellectuals, if noticed, are usually blessed or subsidized. The young head for Europe not to flee, but for vacations, sometimes for conferences. Few American intellectuals live in exile. The question still stands. Where are the younger intellectuals? It is my starting point.

I have not located many-and I am using a criterion of "young," under forty-five or so, that will scandalize the authentically young. Nor are my standards absolute. The "last" generation of American intellectuals is my benchmark, those bom in the first decades of this century. They possessed a voice and presence that younger intellectuals have failed to appropriate.

Yet this misleads; the issue is not a moral lapse but a generational shift. The experience of intellectuals has changed; this is not exactly news, but the causes are unexplored, and one consequence-at least-is unnoticed and profoundly damaging: the impoverishment of public culture.

Intellectuals who write with vigor and clarity may be as scarce as low rents in New York or San Francisco. Raised in city streets and cafes before the age of massive universities, "last" generation intellectuals wrote for the educated reader. They have been supplanted by high-tech intellectuals, consultants and professorsanonymous souls, who may be competent, and more than competent, but who do not enrich public life. Younger intellectuals, whose lives have unfolded almost entirely on campuses, direct themselves to professional colleagues but are inaccessible and unknown to others. This is the danger and the threat; the public culture relies on a dwindling band of older intellectuals who command the vernacular that is slipping out of reach of their successors.

In the following chapters I survey this breach in cultural generations; I offer some possibilities and appraise the costs. Nothing more. A small book confronting a large subject requires a thousand qualifications. I will skip most of them, but several are in order.

Apart from some references to novelists marking the landscape, I confine my account to nonfiction, especially literary, social, philosophical, and economic thought, where I believe the generational break is most emphatic, most injurious. I am excluding music, dance, painting, poetry, and other arts. No single proposition applies to all cultural forms. To be sure, none exist in isolation from the larger society; and I suspect a critical and generational inquiry into other areas might be revealing.

For instance, the migration of fiction into the universitiesthe establishment of "creative writing" centers and writers "in residence"; the rise of the academic or English department novel; the absence of an avant-garde for years, even decadesall this suggests that newer fiction registers the same pressures as nonfiction. The increasing prominence of novels by Latin Americans, Eastern Europeans, and black women also suggests that the creative juices flow on the outsides, the margins, as malls and campuses cement over the center.

Nevertheless the trajectory of fiction is more complex than nonfiction. Perhaps because the poets and novelists were always outsiders, only occasionally noticed, they can subsist as they always have, picking up crumbs off the table.' The plethora of small literary periodicals, sometimes called "little, little" magazines, that print fiction and poetry, indicates that imaginative literature flourishes.

Yet even the moving spirits of the "little, little" magazines allow that their moment seems over; that there are too many journals, the by-product of cheap offset printing and subsidies; and that they seem to have lost their zeal and direction. Insofar as they print exclusively fiction and poetry, unlike their distinguished predecessors, they also testify to cultural fragmentation. Few of these magazines, notes a coordinator of small literary journals, "take a critical stand; essays, even book reviews and correspondence, are less and less common." Nowadays they, seem to be devoted to "knitting up the tattered edges of the present."3

My generalizations are based on American (and Canadian) intellectuals. I exclude the foreign-born and foreign-educated (the Bruno Bettelheims, Hannah Arendts, Wilhelm Reichs) not because of their minimal impact-the opposite is true-but simply to distill out the American generational life. Once they are excluded, their colossal impact can be glimpsed. The individuals I do include hardly add up to the whole. Every selection of intellectuals can be answered by another. There is no royal road to the zeitgeist. Intellectual life resists neat charts; to demand precision when culture itself is imprecise damns an inquiry to trivia. The discussion of a missing generation requires sweeping statements; it means scrutinizing some writers while ignoring others. It necessitates dealing in the glittery coin of generations, long a mainstay of cultural counterfeiters. It also means the risk of being wrong.

I will employ, but not exhaustively define, various categories-bohemia, intellectuals, generations, cultural life. Too many definitions, too much caution, kill thought. Modern analytic philosophy, laboring for decades to establish sound conceptual methods, has only established its inability to think. Its bleak record, of course, does not warrant reckless judgments. With care the coin of decades and generations can be traded.

Since I probe, sometimes ungently, the oeuvre of younger intellectuals, and I question the impact of universities on cultural life, I should state: I do not write as an outsider. When I say "they" or "younger intellectuals," I mean "we." When I take up a "missing" generation, I am discussing my own generation. When I question academic contributions, I am inspecting the writings of my friends and myself. I have published articles in academic journals and a book with a university press. I read academic monographs and periodicals. I love university libraries, endless bookstacks, giant periodical rooms. I have taught at a number of colleges. I do not for an instant pretend that I am made of different and better stuff. My critique of the missing intellectuals is also a self-critique.