Table of Contents

Also by Foster Hirsch

Love, Sex, Death, and the Meaning of Life: The Films of Woody Allen

Laurence Olivier on Screen

A Portrait of the Artist: The Plays of Tennessee Williams

Joseph Losey

Whos Afraid of Edward Albee?

Elizabeth Taylor

The Hollywood Epic

Edward G. Robinson

George Kelly

A Method to Their Madness: The History of the Actors Studio

Harold Prince and the American Music Theatre

Acting Hollywood Style

The Boys from Syracuse: The Schuberts Theatrical Empire

Detours and Lost Highways: A Map of Neo-Noir

Kurt Weill on Stage: From Berlin to Broadway

Acknowledgments

The Motion Picture Section of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; the Library of Performing Arts, New York Public Library at Lincoln Center; the Library of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills; the Beverly Hills Public Library; the Brooklyn College Library; Scribners, for permission to use quoted material from The Killers; Vintage, for permission to use quoted material from The Maltese Falcon, The Big Sleep, and The Rebel; the Thalia Theater, New York City, for their two seasons of films noirs; the Los Angeles Public Library, Downtown Branch, for their rare copies of the original editions of the novels and stories of Cornell Woolrich; the Whitney Museum of American Art; Ted Sennett ; Peter Cowie; Allen Eyles; Murder Ink., New York.

Visual material edited and designed by

Bill OConnell

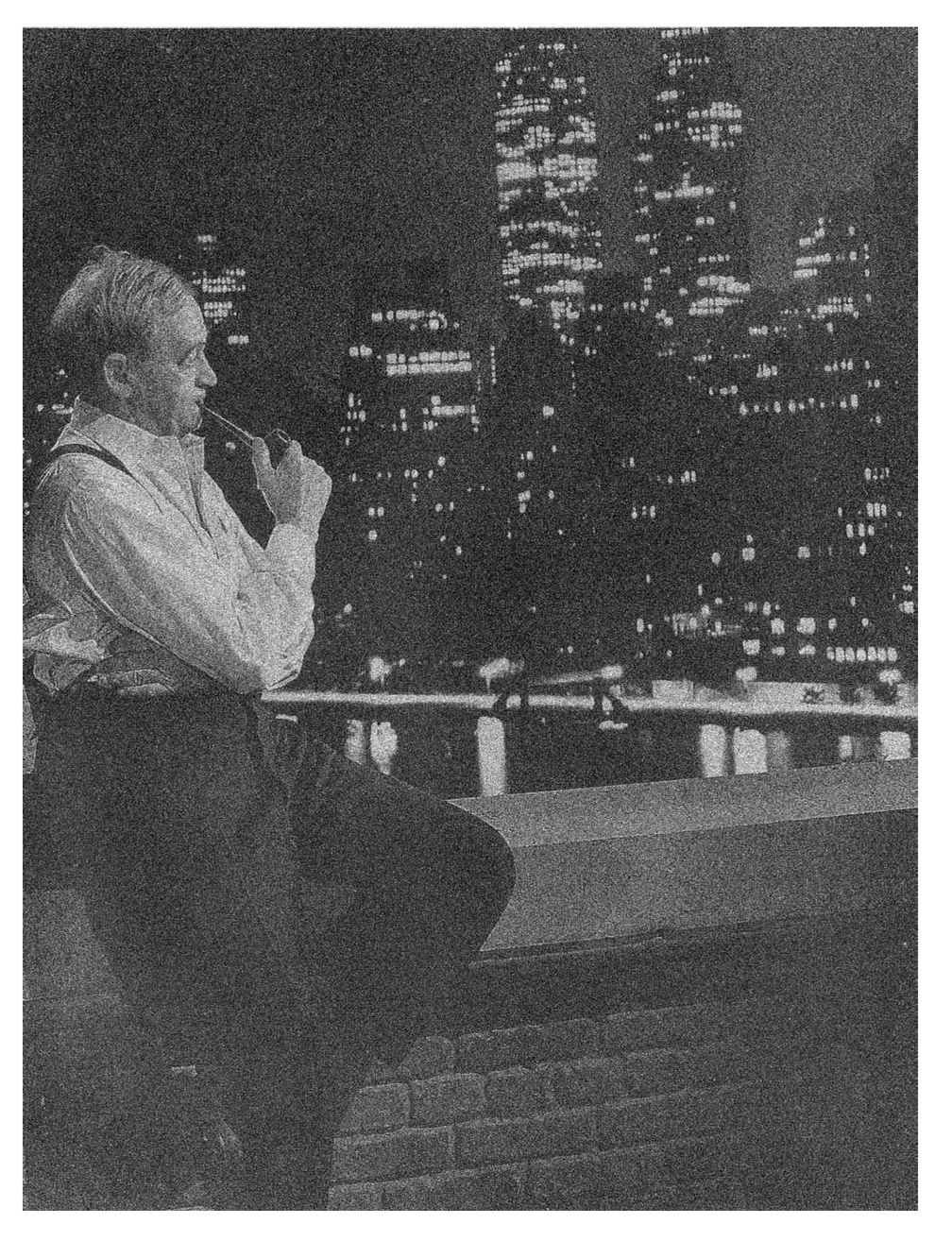

The policeman and the city: Barry Fitzgerald, in The Naked City, looks out over his turf.

The City at Night

A car weaves crazily through the Acar weaves crazily through the dark deserted streets of downtown Los Angeles. As it lurches to a halt, a man crawls out, stumbles into an office building, falls at his desk as he begins to talk into a tape recorder, narrating in a clipped tone a story of a doomed love affair. The speaker, Walter Neff, is an insurance salesman who, on a routine house call, became enamored of a bored and sexy housewife. The two of them, in record time, began an affair and concocted an elaborate plan to do away with the womans husbandafter he had been insured for double indemnity. But their ingenious scheme to defraud Walters insurance company backfired, and the conspirators were undermined by their own mounting distrust of each other, as well as by a shrewd and suspicious claims investigator. The estranged lovers final meeting takes place in the womans house, at night, in dark shadows, in pointed contrast to their first encounter in the house on a sunny mid-afternoon. They shoot each other. The woman dies; the man is able to stagger back to his office where he unburdens himself on tape to the zealous claims man who is also his friend. Having revealed the truth, Walter dies in the friends arms.

After a dinner in his honor, marking twenty-five years of faithful service, a mild-mannered bank clerk named Christopher Cross decides to celebrate by walking home instead of taking the bus, as he usually does. He gets lost in the winding streets of Greenwich Village. Turning a corner, he stumbles upon a scene of violencea man attacking a womanand he runs to call the police as the woman (Kitty Marsh) and her boyfriend (Johnny), who were having a typical argument, confer quickly before Johnny steals away. Kitty and her rescuer strike up a conversation. She is clearly a dame on the make, though the shy clerk is so delighted to be talking to a pretty woman that he doesnt see her for what she is. The poor guy is hooked, a goner; and before he has a chance to get his bearings, he is stealing money from his bank in order to support Kitty in a smart Village apartment. She and Johnny see the older man as easy prey, as someone who can be easily swindled, but they are both too dumb to realize that Chris has no moneythey are as blind to who he really is as he is to the truth about them. They manage, though, to take him for all he is worth and then some, living high on the money he has stolen; and they contrive as well to steal his identity. The clerk is a Sunday painter, and through a chain of coincidences, the two-timing woman begins to sell his canvases as her own work. When Chris discovers the full extent of her duplicity, when she reveals her true face to him and taunts him for his ugliness, his blindness and gullibility, he kills her. But it is Johnny, always slinking around corners and hiding behind doors, who gets caught (and executed) for the murder while Chris goes free, becoming a Bowery bum unable to come forward as the painter of his own now highly-priced work.

These are the stories of two of the most famous films noirs, Double Indemnity (1944) and Scarlet Street (1945). In theme, characterization, world view, settings, direction, performance, and writing, the two dramas are focal points for noir style, as representative of the genre as Stagecoach is of westerns or Singing in the Rain of musicals. Double Indemnity and Scarlet Street are about doomed characters who become obsessed with bewitching women. The insurance man and the bank clerk live regular, self-contained lives, yet a chance encounter releases wellsprings of suppressed passion and forces a radical transformation of character. Both men end up killing the women who have tempted them away from their humdrum lives. Victims of fate, both Walter and Chris fall into traps from which there is no escape; Walter is hopelessly caught when he first meets his clients sultry wife, the clerk is doomed when he rounds a corner and finds what he thinks is a damsel in distress. Both films suggest that the obsessiveness, the irrationality, the violence, the wrenching psychological shifts triggered by their infatuation with luscious, deceitful women were lying in wait beneath the characters bland masks. Sexual release plunges both men into irreversible calamity.

Freed from their former, middle-class selves, both Walter and Chris prove resourceful. Realizing at last a long-held fantasy of duping his company, Walter plots an ingenious swindle. He and his paramour can claim double indemnity if her husband diesor seems to dieon a train. (Deaths by accidents on trains yield high premiums because of their rarity.) Walter applies himself with evident relish to formulating a perfect crime, exulting in the cleverness of his plan to stage the husbands fatal fall from the rear platform of a train; Walter himself plays the husband, whom he has already killed. Chris Cross, though an utter fool in his relations with Kitty, turns out to be a smart embezzler and, when he has the chance to get rid of his nagging wife, rises triumphantly to the occasion. Her former husband, a sea captain she has presumed dead, returns, promising Chris that, for a price, he will disappear once again. But Chris tricks him, and the Captain to his utter surprise is reunited with his wife while Chris walks away a free man. That Chris is not all meekness and pliancy is announced also in a droll scene when, dressed in an apron, he chops meat as his wife scolds him. The emasculating apron notwithstanding, Chris wields the chopping knife heartily, a sly look in his eye: this soft-spoken clerk is obviously seething with murderous rage.

Both Walter and Chris are at first sexually stalled. Walter is unmarried, and his closest attachment is to his colleague, the claims investigator, a father figure whom he tries, perhaps unconsciously, to outwit and to outrage in his clandestine affair with a married woman. The investigator is a figure of authority but also and more crucially of propriety as well; he is a strait-laced bachelor whose life is his job and who is as obsessive in his pursuit of false claims as Walter is in his scheme to defraud the company. The claims man believes Walters nice-guy image, responding to him as the perfectly behaved son, and never for a moment suspecting him as Phyllis Dietrichsons partner in crime. He dislikes Phyllis the moment he sees her, perceiving her as in some way a threat to his own relationship with Walter. He is offended by Phyllis obvious sexuality. Clearly there is a strong connection between the two men; Walter, half dead, races back to the office to confess to his friend and then dies, purged, in the older mans arms. The comradely devotion and loyalty that bind them are an antidote to the poisonous sexuality that links Walter to Phyllis. Is Double Indemnity covertly anti-woman and pro-homosexual? The films tangled, ambiguous, loaded sexual currents, at any rate, are typical of noir thrillers.