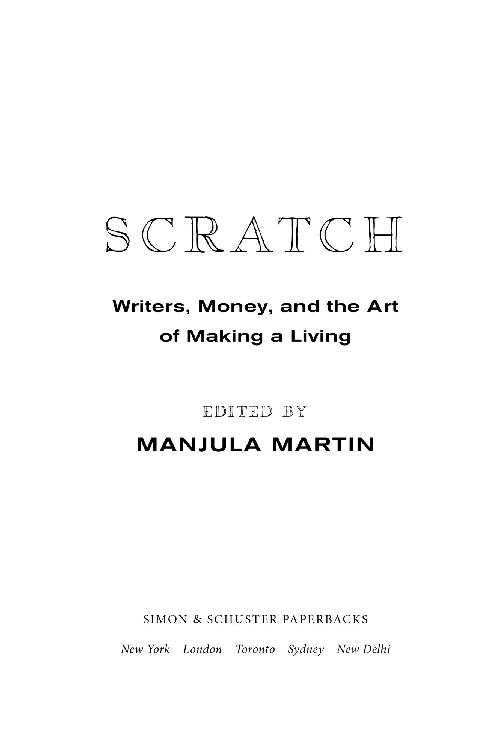

Dedicated to our teachers, librarians, and booksellers, with gratitude for your labor and love

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Manjula Martin

scratch

/skraCH/

verb

1. To scrape the surface of something.

2. To assemble a desired result through hard work and perseverance.

scratch out a living

3. To make something out of whatever is at hand.

made from scratch

a scratch crew

noun

Writing that is extemporaneous or hurried, usually by hand.

she wrote so passionately that it was difficult to read the resulting chicken scratch

informal

Slang for money.

True or false: Writers should be paid for everything they write. Writers should just pay their dues and count themselves lucky to be published. You should never quit your day job. Youll know youre successful when you can quit your day job. Writing is an art, not a business. Writers should be entrepreneurs. Digital technology has destroyed the market for writing. The Internet will set us all free.

Sound familiar?

In every stage of their careers, working writers are in a constant state of negotiation: work and life, art and commerce, writing and publishing. In the public eye and within our communities, authors are said to practice a calling, an art form, a passionbut rarely a job. We are often told by more successful writers to do it for the love, but we are rarely told how to turn love into a living.

Thats where this book comes in.

Scratch magazine was initially developed out of a need for greater transparency in the discussion about work and money within the community of writers. This book deepens that discussion. The interviews and essays that make up this edition come from some of todays most prominent and promising voices, offering candid and informative stories about their experiences at different stages in their careers. In newspapers and on social media, through blogs and informal networks, writers are just now starting to break the silence about what its really like to be working writers. New York Times cultural critic A. O. Scott writes, Nobody would argue against the idea that art has a social value, and yet almost nobody will assert that society therefore has an obligation to protect that value by acknowledging, and compensating, the labor of the people who produce it. In Salon , an authors confession that she is sponsored by her husband unleashed a torrent of think pieces. On Medium, online lightning rod Emily Gould published a frequently shared essay describing how she spent most of a $200,000 advance (spoiler alert: unwisely). And in the New Yorker which itself is perhaps the reigning symbol of opacity in publishingJunot Daz wrote a scathing takedown of racism in MFA programs and barriers to inclusive access in the publishing business. In my own experience as the founder of Scratch and Who Pays Writers? , a crowdsourced database of freelance writing rates, Ive heard time and again from writers who are yearning for any scrap of information they can find about how their own profession functions economically. These heated discussions speak to a need for more openness about how, exactly, literature and the people who make it are valued.

There are stories of artistic and economic struggle in this collection, sure, but more so these are stories of inspiration, empathy, and perseverance. And a few are even pretty damn funny. Taken as a whole, this book is by and for writers who are building careers that deftly encompass all we are: a little bit artist, a little bit hawker, and a whole lot of love. We dont deny that the dreamthe drive and ambition and imagination that make a person decide to do a ridiculous thing like be a writeris important. The love is real. But so is real life. We all need to make a living, whether we make it or not.

If Ive learned one thing while working with these amazing authors on this difficult topic, its that the art of making a living is always evolving; the economics of literature are diverse. Some writers choose to freelancejournalism, copywriting, editing. Some teach and fit in their creative work around their class schedules. Some do a combination of both. Many writers have means of income that have nothing to do with the publishing worldparamedic, law clerk, carpenter. What the authors in Scratch have in common is that they are creative professionals navigating and expanding the relationship between art and commerce every day.

Within this spectrum of authors are those who havent always taken the usual paths to a writing career. Its particularly easy for people with economic and social privileges to say, Do what you love and the money will follow. But its not always so simple for the restthe people without prestigious degrees or parents standing ready to help with a loan. Scratch s vision of a thriving literary community includes authors writing from the margins, people who may have additional obstacles to crafting careers that enable their artistic work but also pay the rent.

When preparing this book for publication, I was often asked by potential writers and readers alike, So, which side are you on: commerce or literature? But to be honest, if this is a contest, I dont much care who wins; Im more interested in how we all got here, and where well go next. Literature and commerce will always be (and have always been) somewhat at odds with each other, uneasy bedfellowsan odd couple. For authors, the path to success is not always one of hardship. Nor is it always a direct route.

The authors in Scratch are looking beyond binaries to seek greater truths about writing, work, money, and publishing. In the business and art of literature there are no rules, no surefire steps to success, no amount of tips or lists that can guarantee you will increase your income or readership. Ultimately, for each and every writer, the answer to the question how do you sell a thing like love? has to be found within their own practice, within the context of their life and work, their resources and desires.

What if each writer could learn to navigate the balance between art and commerce for themselves, making choices according to their means and temperament and finding the best way to put their worktheir own, specific, beautiful workinto the marketplace? What if, instead of parachuting into whatever flame war about publishing and pay is happening at the moment and then forgetting we were ever there, those who make literature and those who buy and fund literature sat down and listened to each others stories?

I realize that its complicated may not be what you wanted to hear when you picked up a book about how writers make a living. I realize its hard when were all thirsty for answers. But, as youll see in the more than two dozen perspectives represented here, there really are no easy answers. There is experience and example and wisdom and luck, and its up to each writer to put them all together into something shaped like a career, to develop a balance between art and commerce that leaves them nurtured enough to keep writing. Besides, we wouldnt be true to our profession if we went for the quick fix, would we? Show me a writer who goes for easy answers and Ill show you a person who is uncurious, uninteresting, too thirsty to make it to the next shimmering oasis. The authors in the following pages are right there in the weeds along with readers, navigating the complex relationships among art, life, and work at different stages in their careersand revealing the heart of American literature in the process.

Care to join us?

EARLY DAYS

OWNING THIS

Julia Fierro

M y family moved when I was in fourth grade, into a ramshackle home on a desirable woodsy island off Long Island Sound. The location and school district seemed a steal despite the houses decrepitudemoldy ceilings, termite-infested walls, and a well that pumped metallic-tasting waterand my father, a Southern Italian immigrant born into poverty and pestilence, also a survivor of WWII, performed miracles with jars of spackle and the discontinued paint hed bought half off at some faraway hardware store he frequented for its sales. We loved our new home, and delighted in calling it our mansion, despite the way it seemed to sag under its sad history. Abandoned by the previous owners , the pert Realtor explained, a family with three sons . She had sped through the summary teenage boys turned delinquent, drugs and alcohol, a messy divorce , etc., etc. Years later, wed hear the full story. The mother of the wild boys had tried to kill herself, twice. First, by stabbing herself in the kitchen where wed sing Happy Birthday and hold Christmas family dinners. Second, and this time successfully, by jumping out the window in the room that would become my bedroom.